You can get whiplash inside the Pentagon. The last time the Defense Department achieved notoriety as a platform for views on Saudi Arabia was in 2002, between the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. That’s when a Rand Corp. analyst told a high-level panel behind closed doors that the kingdom was “active at every level of the terror chain, from planners to financiers, from cadre to foot soldier, from ideologist to cheerleader.” Washington, he said, should declare the Saudis the enemy and threaten to take over the oil wells if they didn’t do more to combat Islamist terrorists (the briefing was 10 months after the 9/11 attacks, in which 15 of the 19 terrorists were Saudi).

The Pentagon quickly distanced itself from Laurent Murawiec’s presentation to the Defense Policy Board. Secretary of State Colin Powell called the Saudi Foreign Minister to apologize. Murawiec, who made the presentation on his own time, resigned from Rand several weeks later.

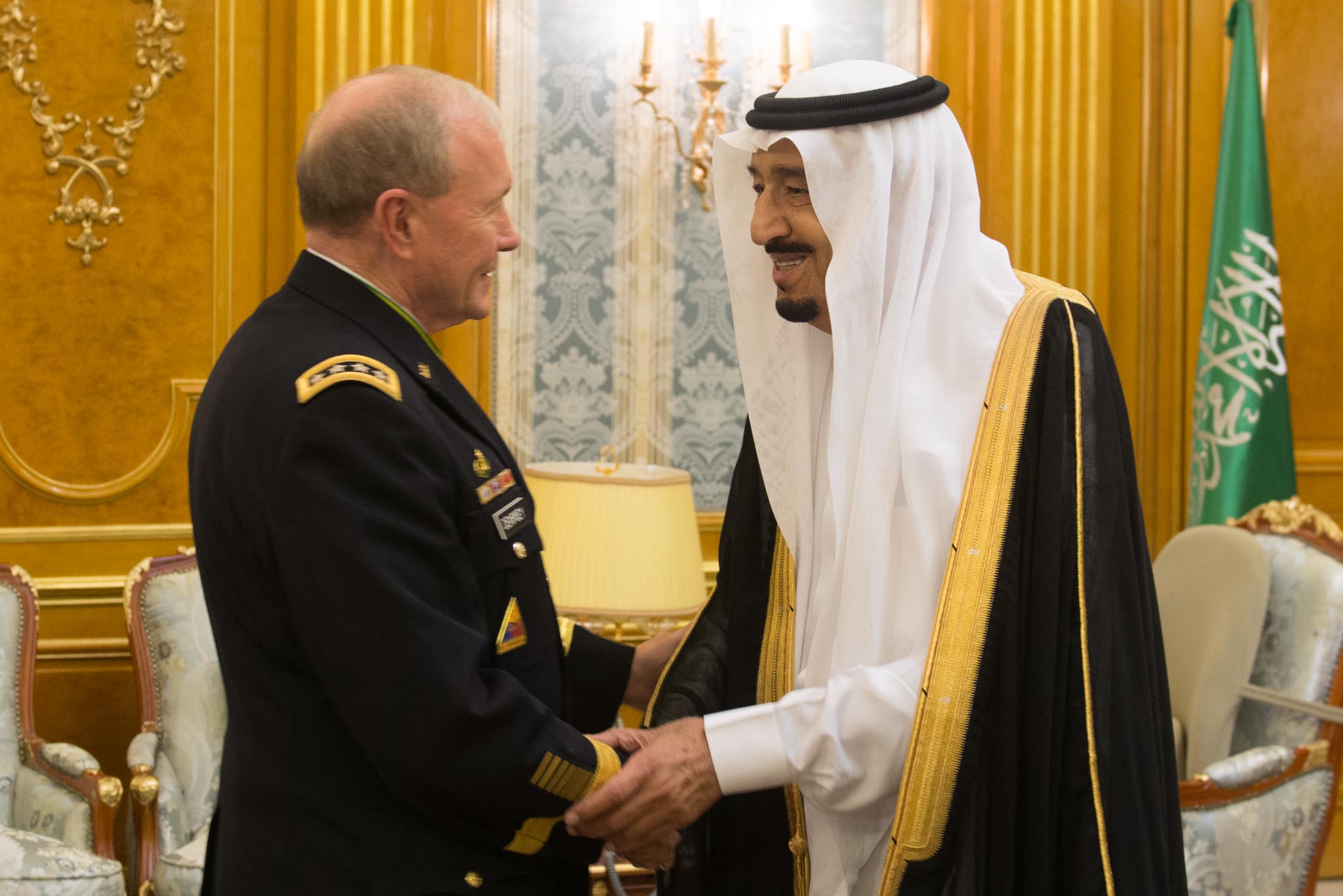

On Monday, the top U.S. military leader, Army General Martin Dempsey, announced the Pentagon would be conducting a “research and essay competition” to honor Saudi King Abdullah, who died Jan. 23 at 90, as “a man of remarkable character and courage.”

Critics pounced.

“I wonder if Raif Badawi, the Saudi blogger who has been sentenced to 10 years in jail and 1,000 lashes for postings critical of Islam and the House of Saud is eligible to enter?” one posted on Dempsey’s Facebook page. “That’s an essay that might be worth reading.”

Foreign-policy experts questioned Abdullah’s reputation as a King who pushed for change in Saudi society. “There were persistent stories alleging that Abdullah was a reformer, but no one could ever articulate for me what he actually stood for and wanted. It seemed to me that he wanted what everyone in the Saudi royal family wants — stability and business as usual,” Steven A. Cook, an Arab expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote Monday. “There is no denying that the Saudis under Abdullah had an extremism problem about which they were apparently in abject denial until terrorists started targeting them in 2003. More recently, Abdullah oversaw the beheading of eighty-seven individuals in 2014, mostly poor guest workers that no one cares about. So far this year, which is only twenty-six days old, Saudi executioners have separated ten more people from their heads.”

And you don’t have to rely on ivory-tower scholars. Then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in a secret 2009 memo that Saudi Arabia is an ATM for terrorism. “Donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide,” she wrote, adding that the King and his government had been reluctant to shut down such cash pipelines.

This is the challenge of the 21st century world. With the end of the Cold War, forces have been unleashed that have toppled dictators along an arc of crisis from Libya to Egypt to Iraq. Saudi Arabia’s monarchy is the key to U.S. policy in the region, and it, too, is a non-democracy that hardly squares with U.S. ideals.

The U.S.-Saudi relationship boils down to quid-pro-petroleum: We need their oil, and they need U.S. military protection. The Saudi military’s F-15 fighters, AWACS aircraft, Patriot missiles, M-1 tanks, Bradley fighting Vehicles and AH-64 Apache helicopter gunships are all U.S.-built and maintained. Absent continued U.S. support — spare parts, upgrades, software — for such an arsenal, Saudi Arabia would find itself defenseless in a matter of months. Shi’ite Iran’s growing clout in the region, just across the Persian Gulf from the kingdom, unnerves the Sunni Saudis.

Dempsey was stationed in Riyadh, a month after earning his first star as a brigadier general, when Murawiec gave his infamous Pentagon briefing. He was overseeing 350 U.S. troops and civilians, and more than 1,000 contractors, as chief of the Saudi Arabian National Guard Modernization Program. The commander of the Saudi Arabia National Guard: none other than Abdullah, who would become King two years after Dempsey left Saudi Arabia.

“In my job to train and advise his military forces, and in our relationship since, I found the King to be a man of remarkable character and courage,” Dempsey posted on his Facebook page Friday. “He will be truly missed and his loss will be felt by his country and ours.”

But don’t confuse the Saudi Arabia National Guard run by the future King, and trained by Dempsey, with the U.S. military’s National Guard.

“Saudi Arabia really has two different armies,” the senior U.S. enlisted man assigned to SANG from 2006 to 2008 wrote in 2009. Then-U.S. Army Sergeant Major James E. Wafe Jr. added:

The Saudi Arabia National Guard (SANG) is not like the U.S. National Guard. It is a tribal force forged out of those tribal elements loyal to the Saudi family. The SANG’s mission is to protect the royal family from internal rebellion and the other Saudi army should the need arise.”

That other, “official” army’s rule, Wafe continued, is “to protect the country from external threats, and to serve as a balance against SANG, should the royal family decide to eliminate some clan hostile to the King’s rule.”

Plainly, Dempsey and his troops had their hands full training the Saudi national guard, and balancing its capabilities against those of the Royal Saudi Land Forces.

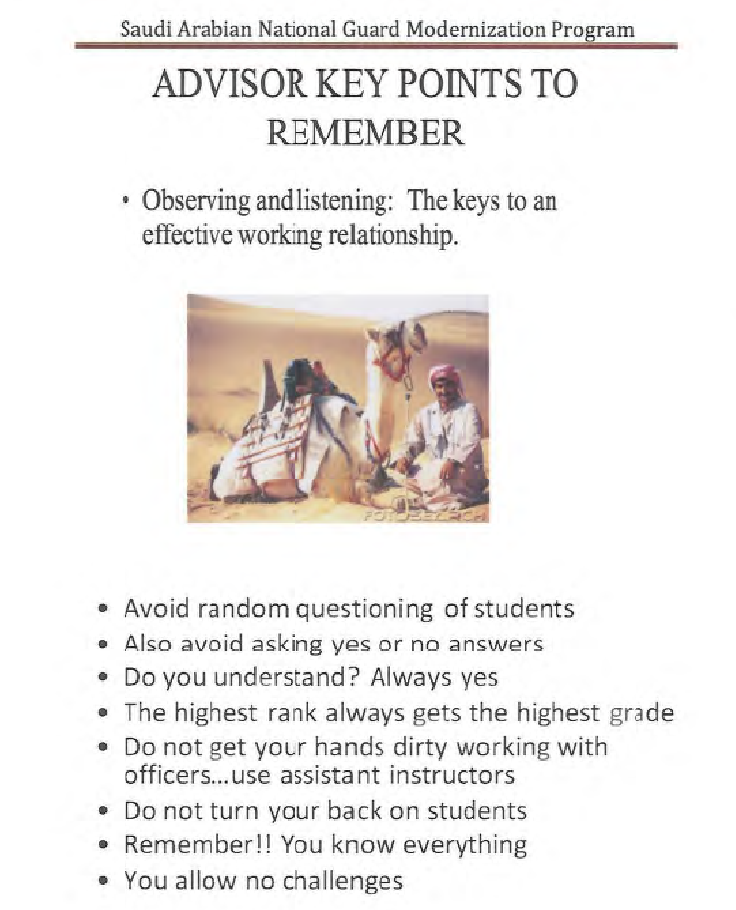

Wafe wrote of the challenges associated with training SANG’s non-commissioned officers — the sergeants and others that are the backbone of the U.S. military — to fight:

The Western Region really wanted their NCOs to be as strong as our NCO Corp, but the lack of knowledge made them not confident in them and also they thought they couldn’t be taught. We had sergeants that held the same rank and position for years, such as a LAV (Light Armor Vehicle) driver. A lot of times, they made the NCOs serve tea and coffee for the generals. We knew we couldn’t teach the NCOs everything, because of time restraints, so we mainly focused on the basic skills to protect and serve his King. These basic skills consisted of marksmanship with their individual assigned weapons and crew serve weapons, Physical Fitness, Night Vision Goggles, and map reading. Their duty hours were only six hours a day, ranging from 0600-1200; this didn’t give us much time to train … The trend that I observed about the SANG Soldiers is that once they return from their Security Mission, they tend to forget everything and we are re-teaching the same skills over again. This becomes a long drawn-out process and a lot times it feels like we only move the SANG Anny inches and this is a plus when it comes to training …

The Omar bin Kattab Brigade (OKE) is stationed in Taif … The NCOs within this Brigade were even worse than the Western Region. The NCOs here did not have any education and they did not know how to read or write. A lot of our training here was hands-on and that took a while to conduct. The equipment they had there were old and they were lacking tools to keep up the maintenance. The Brigade Commanders did have unit money to spend on equipment, but many of them bought furniture for their office and home, instead of taking care of their equipment. Some of the soldiers did not want to replace their periscopes on their vehicle because it was a battle wound from Desert Storm and they wanted to show off their treasured badge of courage. Overall these NCOs and soldiers wanted to learn, but no support was enforced by their higher command …

The SANG Army took on the U.S. tactical and gunnery manuals, but it takes us a while to translate it into Arabic. One major issue we did realize is that an Arabic word doesn’t really mean the same in English. When the [interpreters] are translating the English version to Arabic, sometimes they have to find the word that means the closest to the English word. This can cause a big problem when it comes to gunneries because when it comes to bullets and safety, we have to be very specific. In Arabic, there can be a lot of gray areas which creates the opening for an unsafe act to happen …

The mentality the Saudi officers is if I am the only one in the organization who knows how to … Then I am important and people have to come to me. If others know what I know … then I have lost my power and importance. So U.S. advisors need to know that training the trainers does not always work … the knowledge is not passed down because ‘Information is Power.’

Wafe, who as an enlisted soldier was more likely than an officer to call ’em the way he saw them, issued guidelines for those U.S. troops who would follow in his footsteps to train SANG forces:

O.K., so the Saudi monarchy is an archaic autocracy with a U.S.-supplied military dedicated to keeping it in power. Bottom line, as Donald Rumsfeld might have said: You defend your oil with the army you have, not the one you wish you had.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com