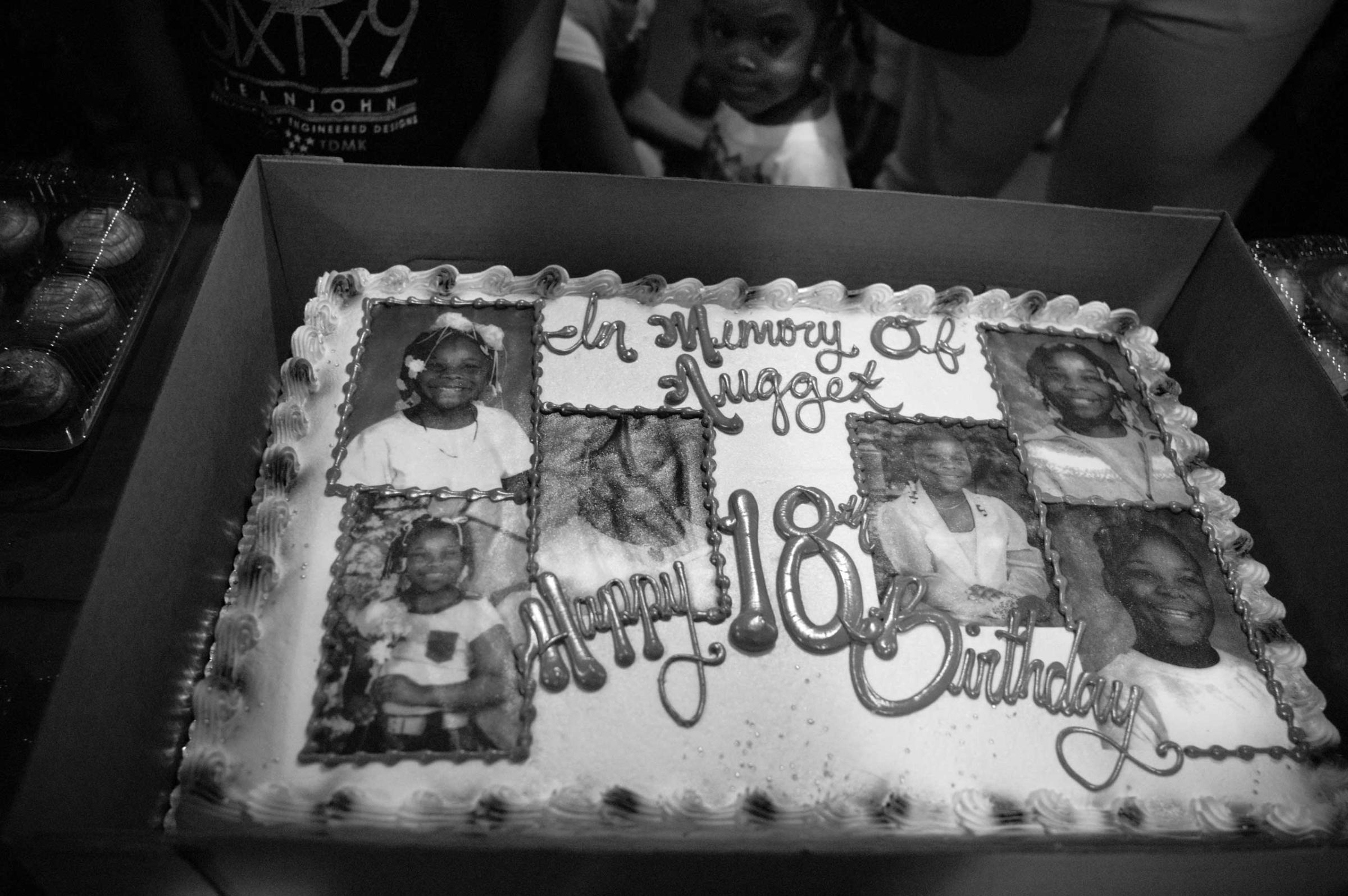

Siretha White was at her 11th birthday party when she was killed in 2006. Nugget, as she was known to her family, had been celebrating in her cousin’s home when gunman Moses Phillips, who had reportedly been aiming at a man who was on the porch, shot through the front window fatally wounding her as she ran toward the back of the house. It was a sudden, shocking death that devastated the Whites and many others in their neighborhood of Englewood, Chicago.

The young girl’s story quickly caught the attention of photographer Carlos Javier Ortiz, who had planned on documenting the effects of gun related violence on communities not long before. Shocked by the brutal nature of the incident — and struck by how similar it was to the death of 14-year-old Starkesia Reed, who had been killed by stray gunfire a few blocks away just days before — he approached the White family with the aim of documenting the aftermath.

“The next day I was at the house. There was a birthday cake on the table that didn’t get cut [and] I spent about two hours talking to [Siretha’s] mother’s cousin outside,” Ortiz says. “We talked about a lot of things that were wrong in this neighborhood.”

Englewood often leads the city of Chicago in homicides, though there was a reported 19 percent decrease in 2013.

“[Siretha’s] mother called me that same night, she is a really good friend of mine now, [and said]: ‘I want you to do something. I want you to come to the radio station with me tomorrow and photograph me.’ [And then] she basically let me follow her home.”

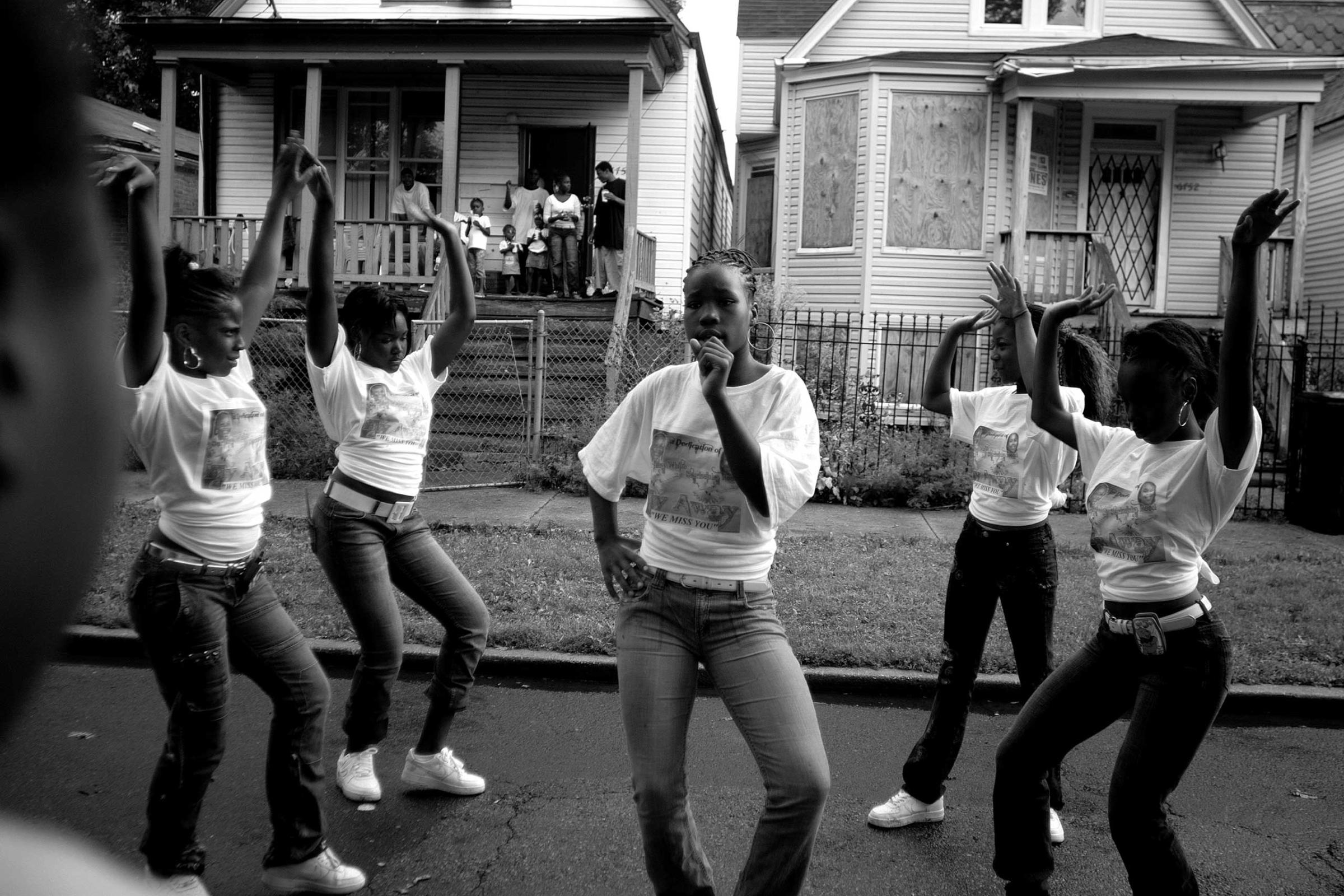

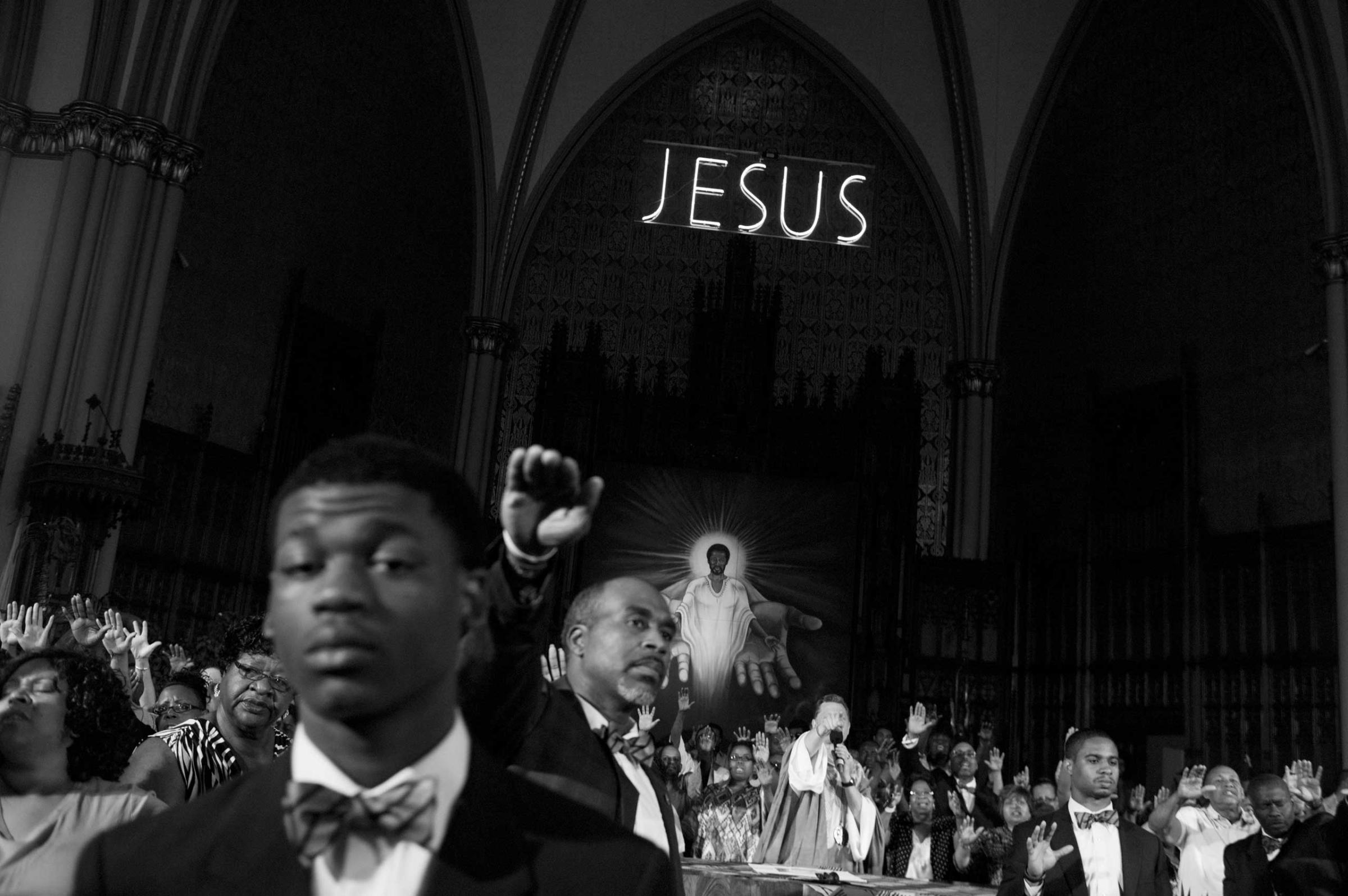

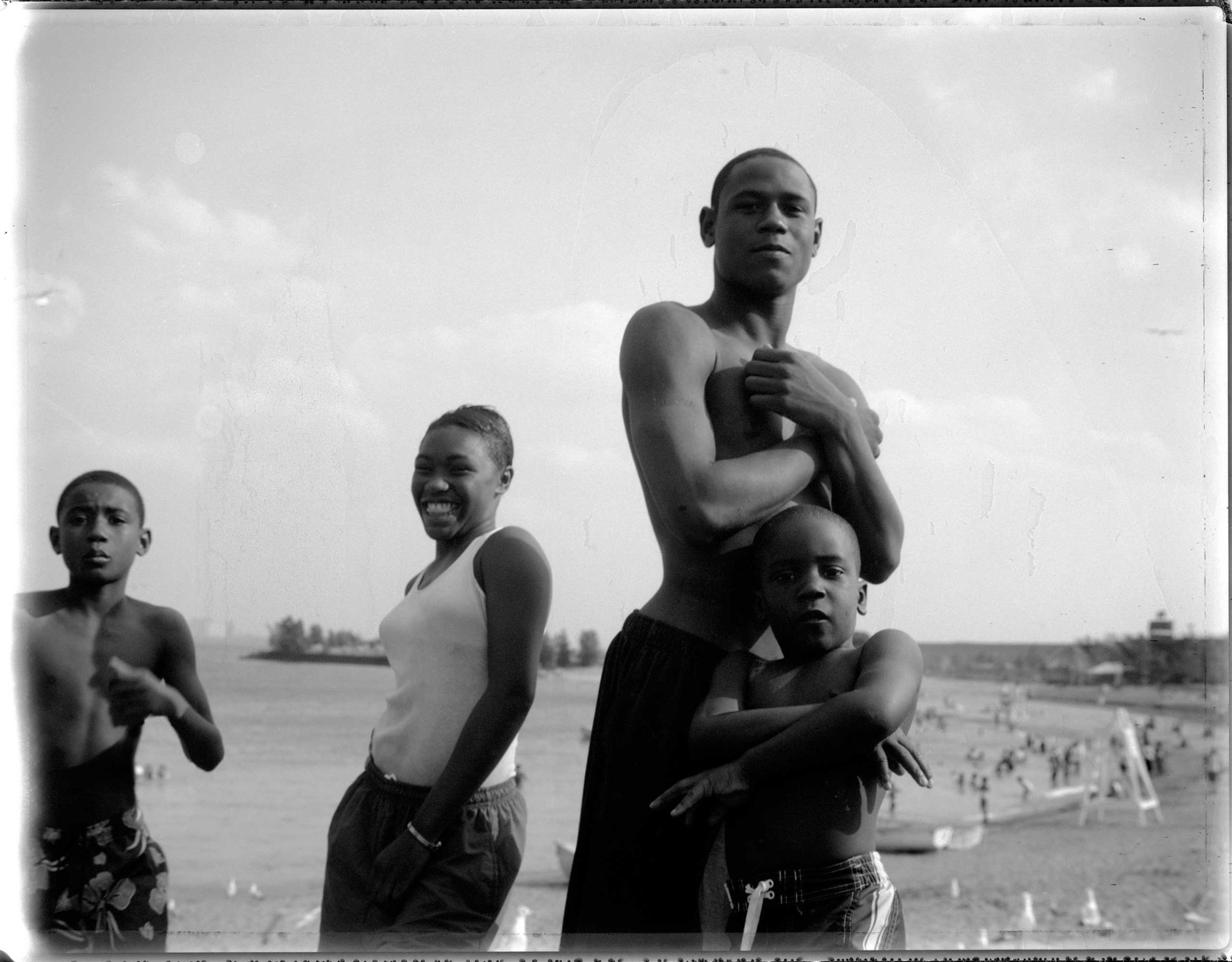

Starting that day, Ortiz embedded himself with both the Whites and a larger community, locally and nationally, in an attempt to start a conversation about gun violence and its consequences. It evolved into a project that spanned eight years, and one that saw him travel between neighborhoods in Chicago and Philadelphia. Now, much of the work appears in his newest book, We All We Got, which will be on show at the Bronx Documentary Center in New York until March 22, 2015.

The images that emerged from his project are as powerful and heart-breaking as they are unnerving and thought-provoking. In one photograph, we see Albert Vaughn, who was beaten to death with a baseball bat, in his coffin as relatives mourn. In another, we see the mother of Fakhur Uddin grieving outside the store where he was killed as he opened the family business in August, 2008.

Ortiz sees the often difficult work he produced as a collaboration and would sometimes show his photographs to subjects. And while he sought to preserve journalistic distance, he couldn’t help but feel involved on a personal level with the communities, and individuals, who opened up to him.

“I saw boys and girls growing up and I couldn’t really do anything for them. I would see [a] change in the boys when they got to be 11 [or] 12. They would start walking differently, acting differently,” he says. “They start to pick up all these things from the other guys in the neighborhood, who picked them up from the other guys. So it’s like a circle.”

Indeed, having embedded himself with families for so long he started to witness tragedies unfold around him: “[The White’s] next door neighbor, he would DJ and sell shoes on the side, just to support his family. One day somebody robbed him and just murdered him.”

“It started becoming really hard. I started losing people too,” he adds. “They were my friends, people in the neighborhood were my friends. That was kind of a big wake up call.”

Carlos Javier Ortiz is a documentary photographer and experimental filmmaker based in Chicago. We All We Got is available now. The Bronx Documentary Center will host an opening reception for the book Jan. 24, 2015 and will show Ortiz’s work from Jan 24 to March 22, 2015.

Richard Conway is reporter/producer for TIME LightBox.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com