Feminista Jones is a mental health social worker and feminist writer from New York City.

At a recent premier of the new Civil Rights Movement era movie Selma, Tony Award-winning actress Phylicia Rashad commented for the first time on the allegations of drugging and sexual assault that have been made against her former co-star and close friend, Bill Cosby. In a brief interview, Rashad said: “What you’re seeing is the destruction of a legacy. And I think it’s orchestrated. I don’t know why or who’s doing it, but it’s the legacy. And it’s a legacy that is so important to the culture.”

I feel for anyone falsely accused of such crimes, as I know that such fabrications can ruin one’s life. I’m incensed, however, when assault victims’ allegations are dismissed outright, particularly by women, and further, women of color. As a black woman and survivor of sexual assault, I struggle with immediately siding with a black man accused of rape simply because of cultural allegiance and respect for his work.

Rashad is not the only well-known black woman to come to Cosby’s defense. Whoopi Goldberg also defended Cosby, and singer and actress Jill Scott expressed her disbelief of the claims on Twitter, citing Cosby’s “magnificent legacy.” Hip-hop artists MC Lyte and Azalia Banks have also defended Cosby, even going so far as to suggest he’s being set up.

How could Rashad, a woman who has been affectionately dubbed the “mother of the African American community,” and who has portrayed strong, progressive women, minimize the stories of dozens of women? How could so many prominent black women publicly dismiss the words of dozens of women who claim Cosby harmed them in some way?

One reason some have defended Cosby is because many of the women coming forward are white and there is a well-documented history of white women making allegations against black boys and men that have destroyed towns and sparked resistance movements. Black women often feel protective of our men, having been racially mistreated ourselves. As their mothers, daughters, and sisters, many of us experience a defensive jolt when accusations are made against them because of generations of racialized trauma and institutional abuse, and we don’t want to contribute to any more harm being done to our men. This point was eloquently made when supermodel Beverly Johnson came forward with her story of being drugged by Cosby.

What I don’t understand is how they, as women, can defend him against so many allegations that suggest Cosby was methodical and intentional in his approach to allegedly drugging women and patterns of physical assault. I was just as bewildered when black women defended Ray Rice after the video surfaced of him punching his then-fiancée, Janay, into unconsciousness. The evidence was clear for all to see, yet there were those who made excuses and even blamed Janay for what had been done to her. All of these excuses and defenses have been made despite black women suffering disproportionately from domestic violence and sexual assault.

I am black and I am a woman. I cannot and will not choose which identity supersedes the other when conversations like these go public. Black women are too often charged with prioritizing race over gender under a cloak of a racial “unity” that doesn’t always benefit us because of sexism and misogyny within our communities. We’re told to keep these talks “in house” so that we don’t let white people see our internal conflicts, which, we’re told, impede progress as a people. This silence has caused, in some cases, irreparable damage not only to our bodies and minds, but to our families and communities.

I responded similarly when I first heard of Autumn Jackson, who was jailed in 1997 for extortion after claiming Cosby was her father. I assumed, like many, that she and her mother were just trying to get money from him. Jackson’s conviction was later overturned. And in 2000, when Lachele Covington filed a police report alleging that Cosby had been sexually inappropriate with her, I doubted her claims, thinking she was just a starlet trying to “come up.” Heathcliff Huxtable, err, Bill Cosby would never do such a thing, right?

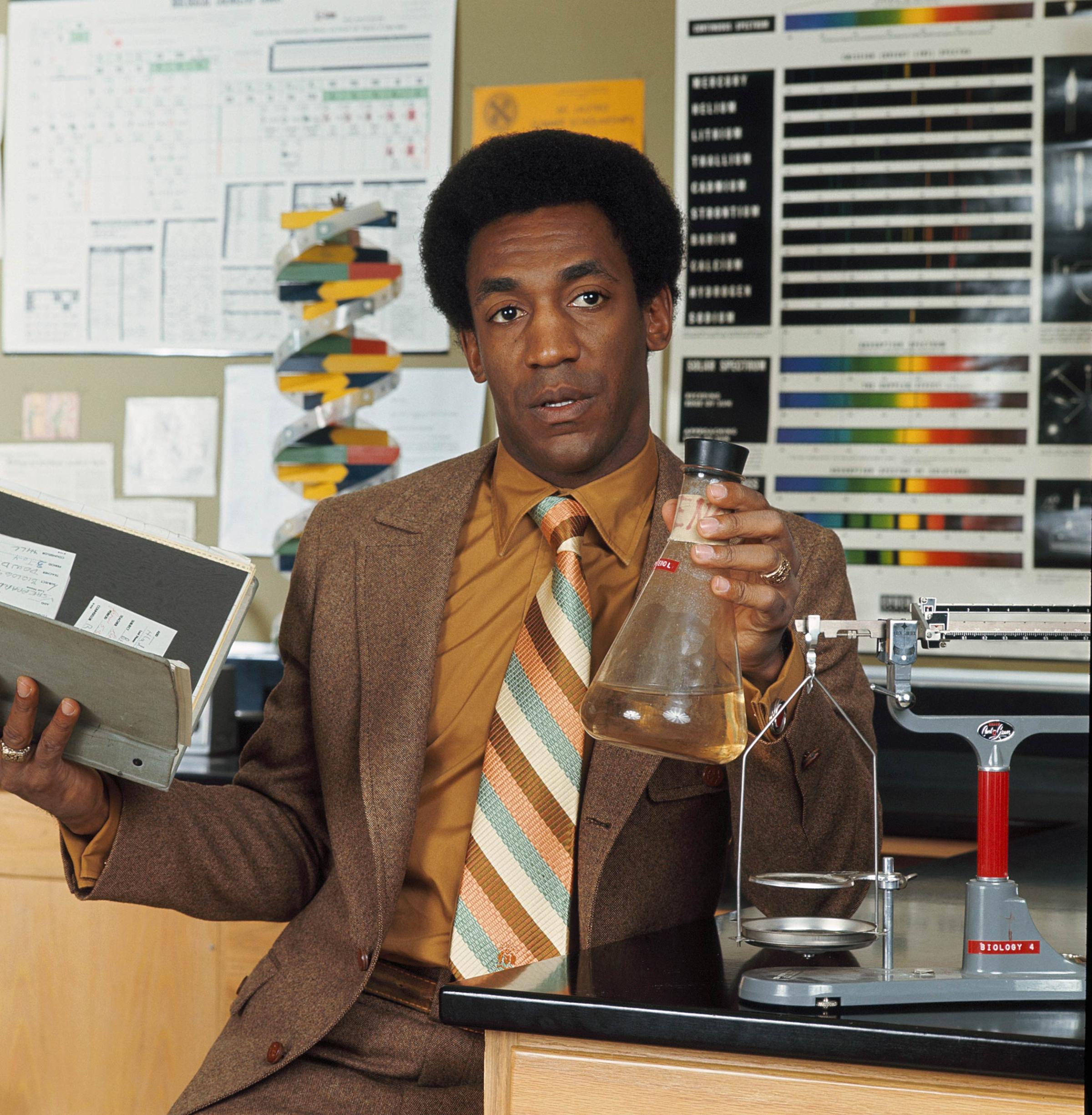

Some black men have defended Cosby because they fear being guilty by black association, or because they have faced similar accusations themselves. In a society that often condemns entire minority groups for the actions of a few, and in which black men are seen as inherently criminal, the rush to defend prominent black men being accused of such heinous acts is almost compulsory and even understandable. Considering how many people adopted Cliff Huxtable as their surrogate father, the defense of that character, more than Cosby, the man, is to be expected.

I’m one of the “silent” women. I’m a woman who has been sexually assaulted and couldn’t bring myself to report what happened to me because I didn’t think anyone would believe my word over the word of my attackers. I convinced myself that I wouldn’t have a lot of support because, where I’m from, sexual assault and abuse are rarely addressed. So, like most survivors, I did and said nothing for years. I only became comfortable sharing my story after connecting with other survivors who were open about their experiences.

I cannot simply set these women aside in favor of a conspiracy theory. I cannot forget the women who have not yet come forward because they fear the harassment and probing that comes with accusing a beloved celebrity of wrongdoing. I cannot forget any victim of sexual assault, regardless of race, who has been silenced by disbelief, disregard, and a society that places entirely too heavy a burden of proof on victims instead of accused perpetrators.

We have to change the way we approach our handling of sexual violence as a society, especially in black families and communities. The silence is damaging, and if we want to experience true progress as a people, we can no longer protect those within our families and communities who harm others.

Feminista Jones is a mental health social worker and feminist writer from New York City.

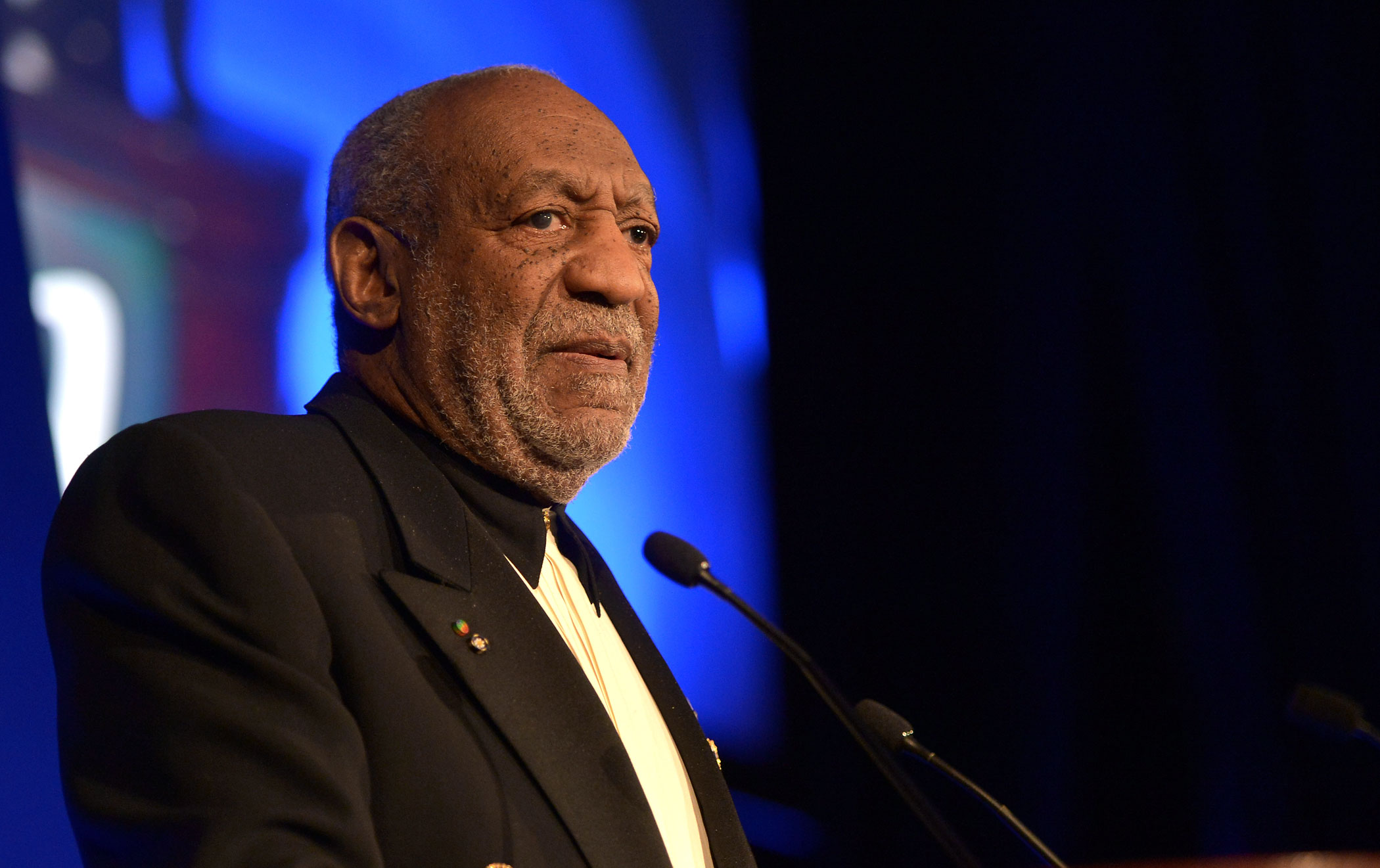

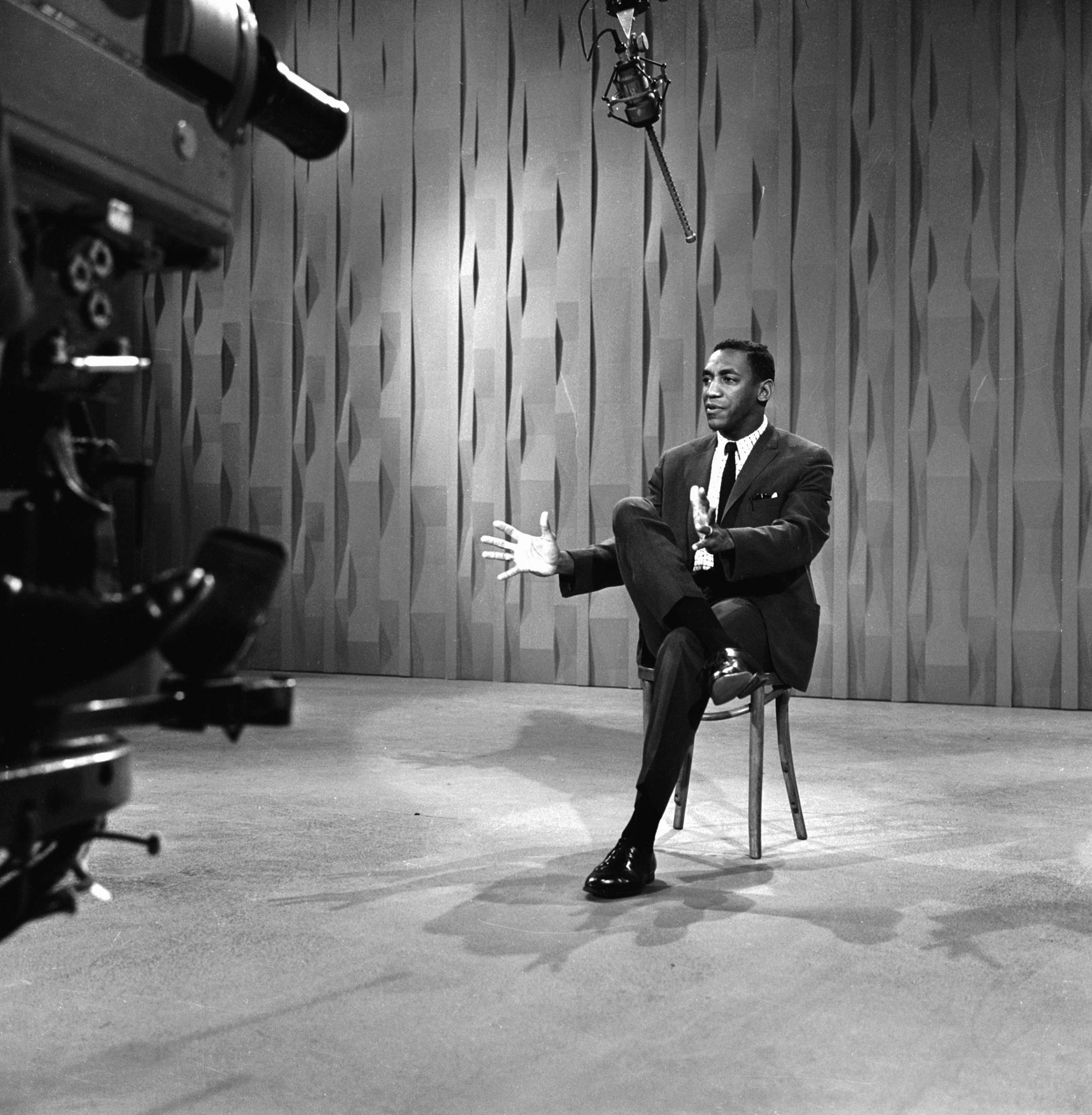

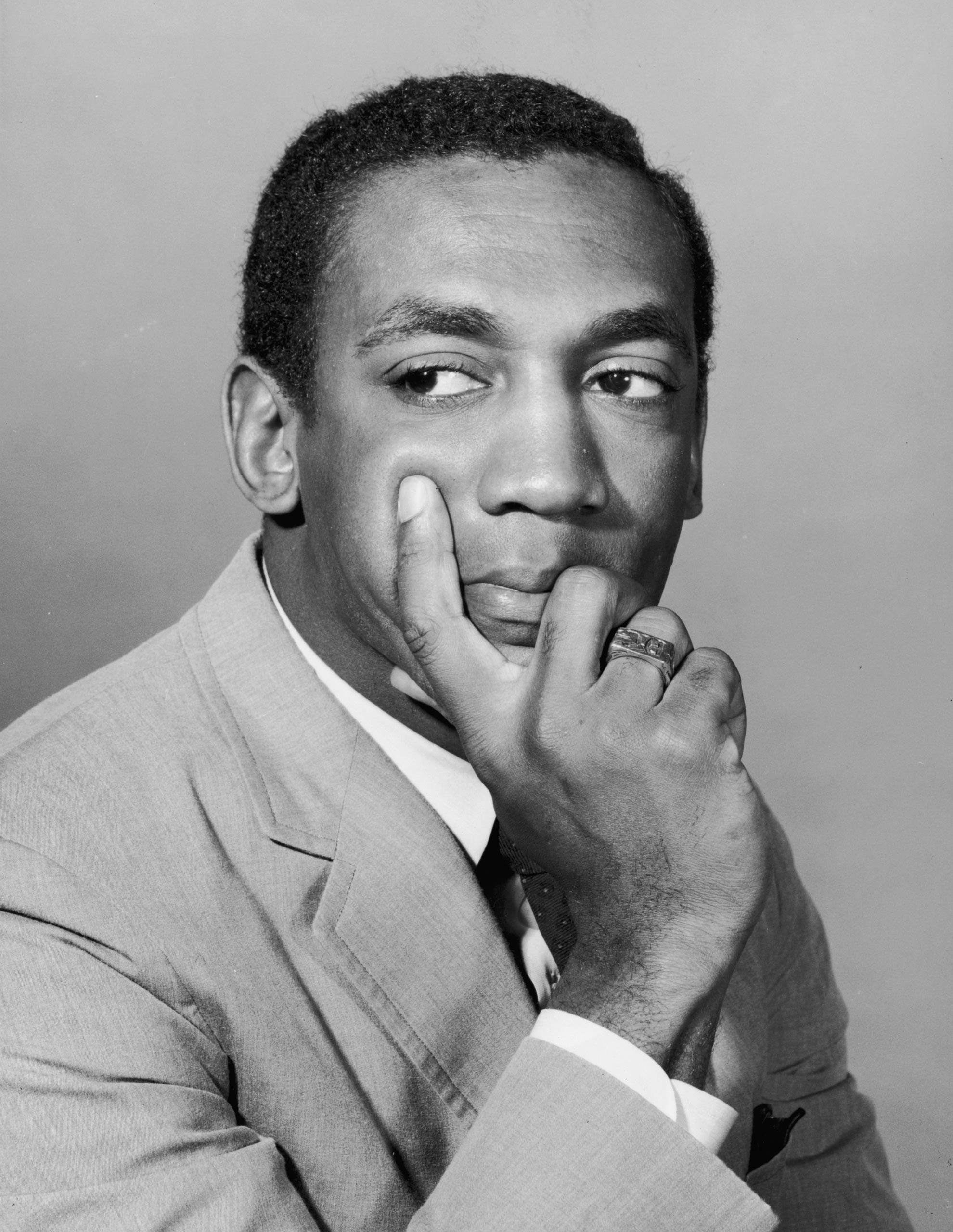

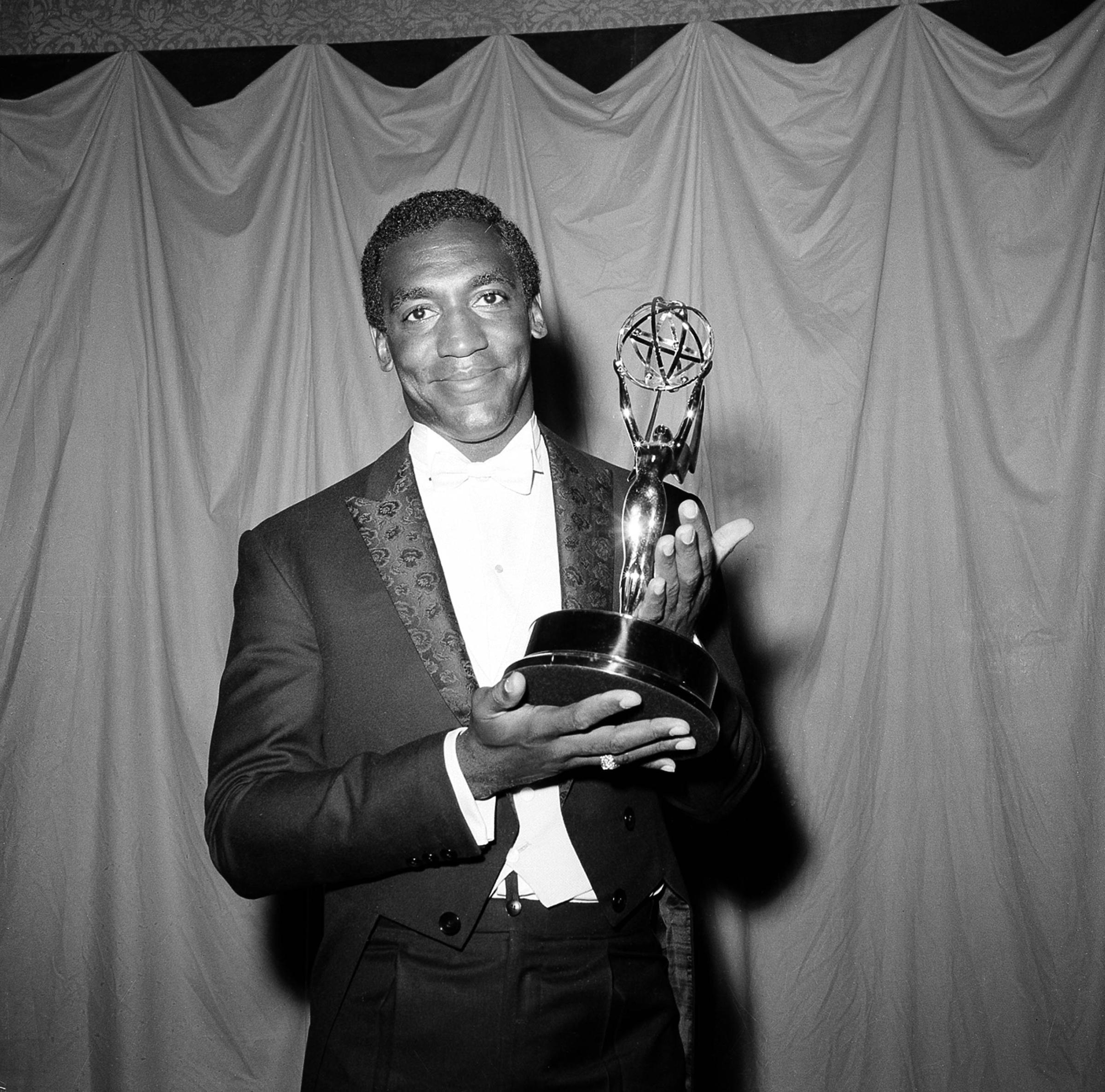

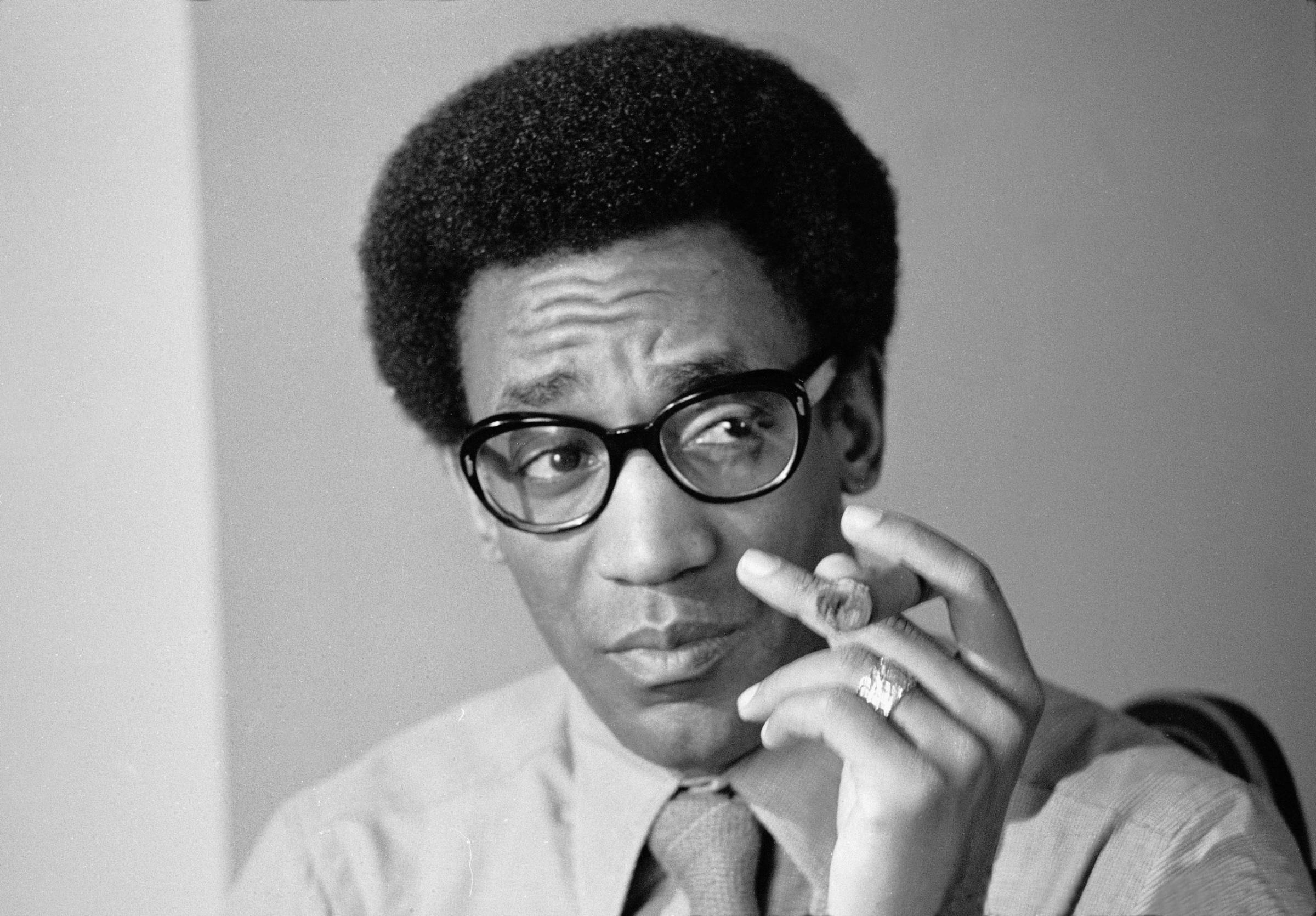

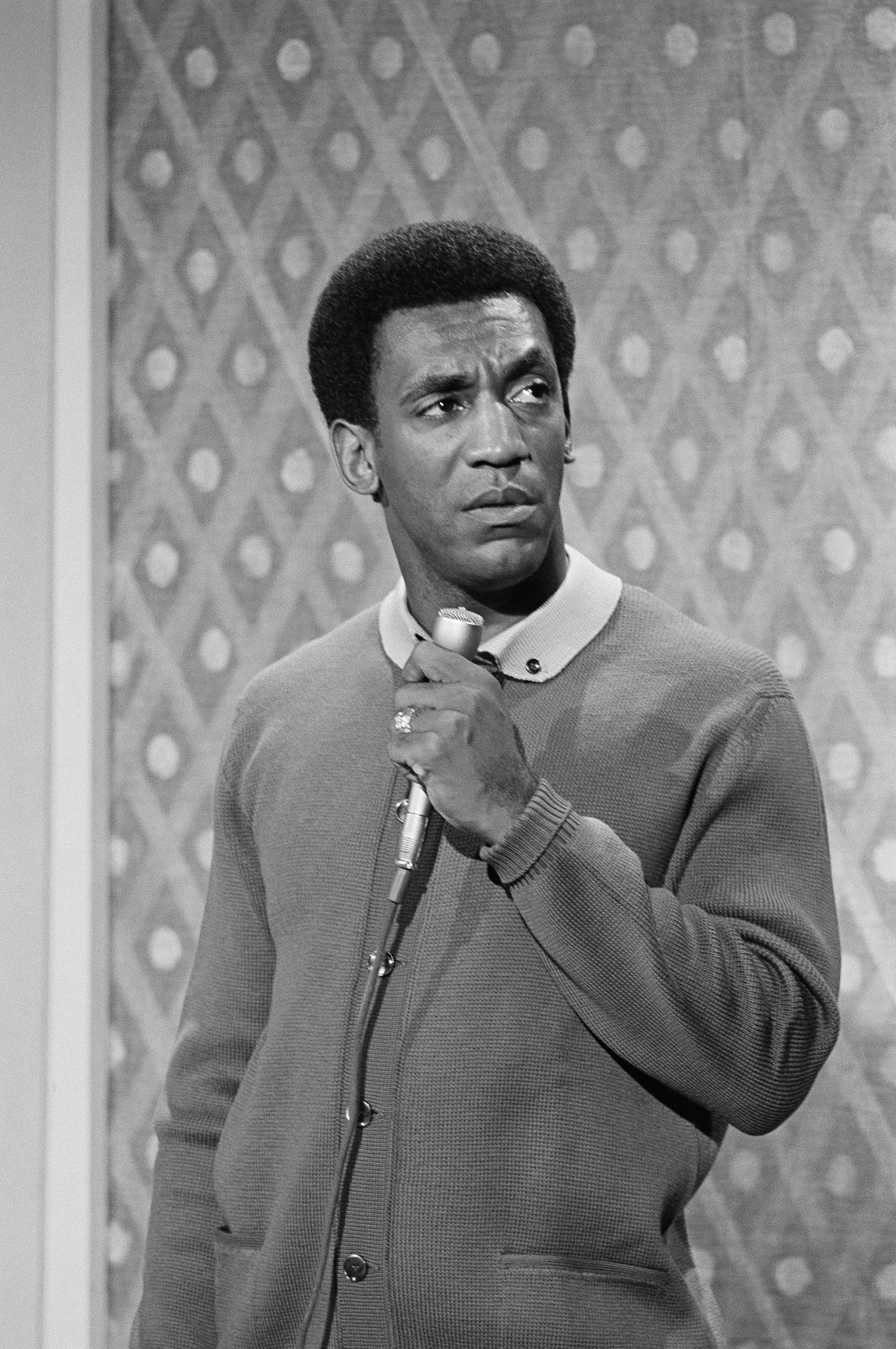

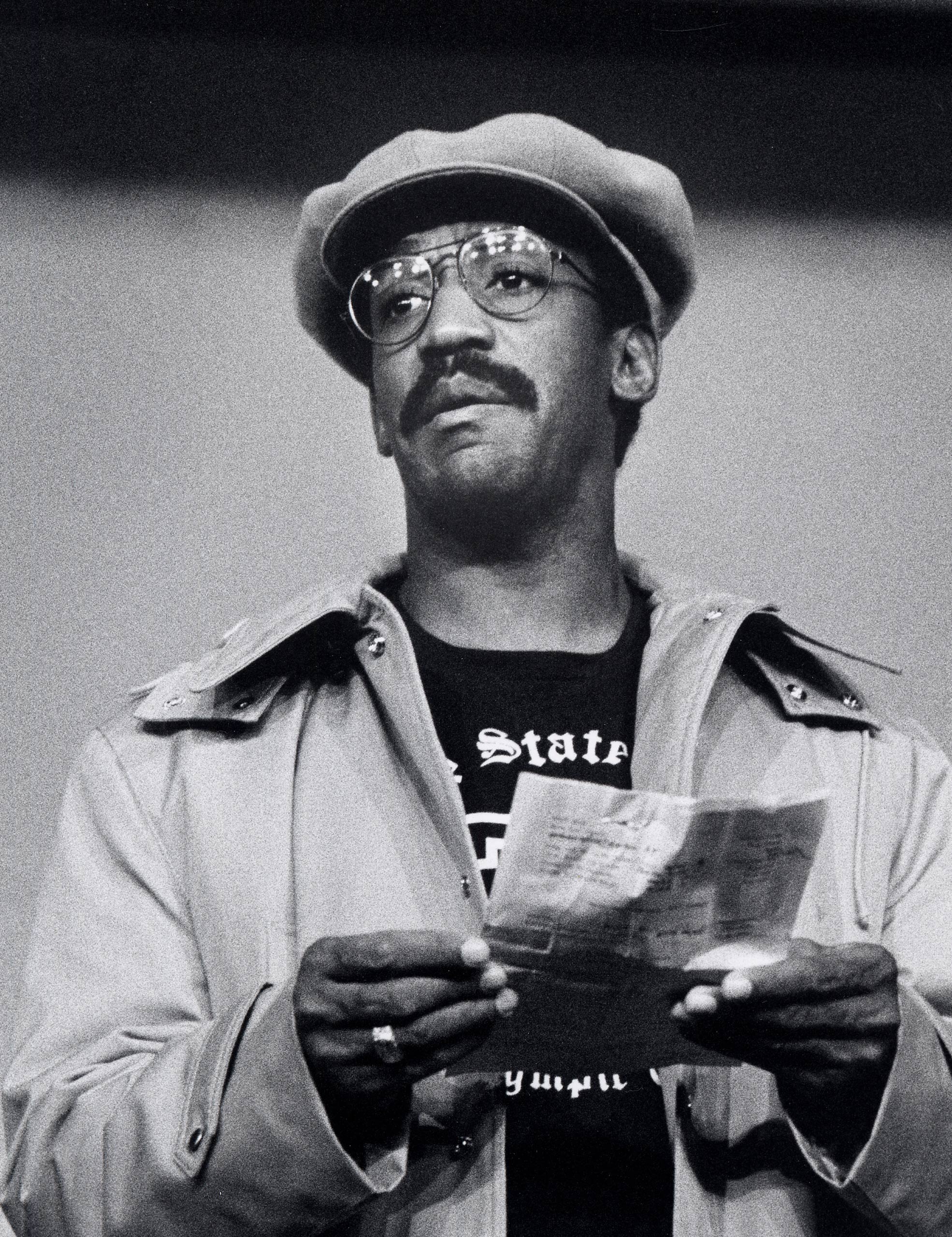

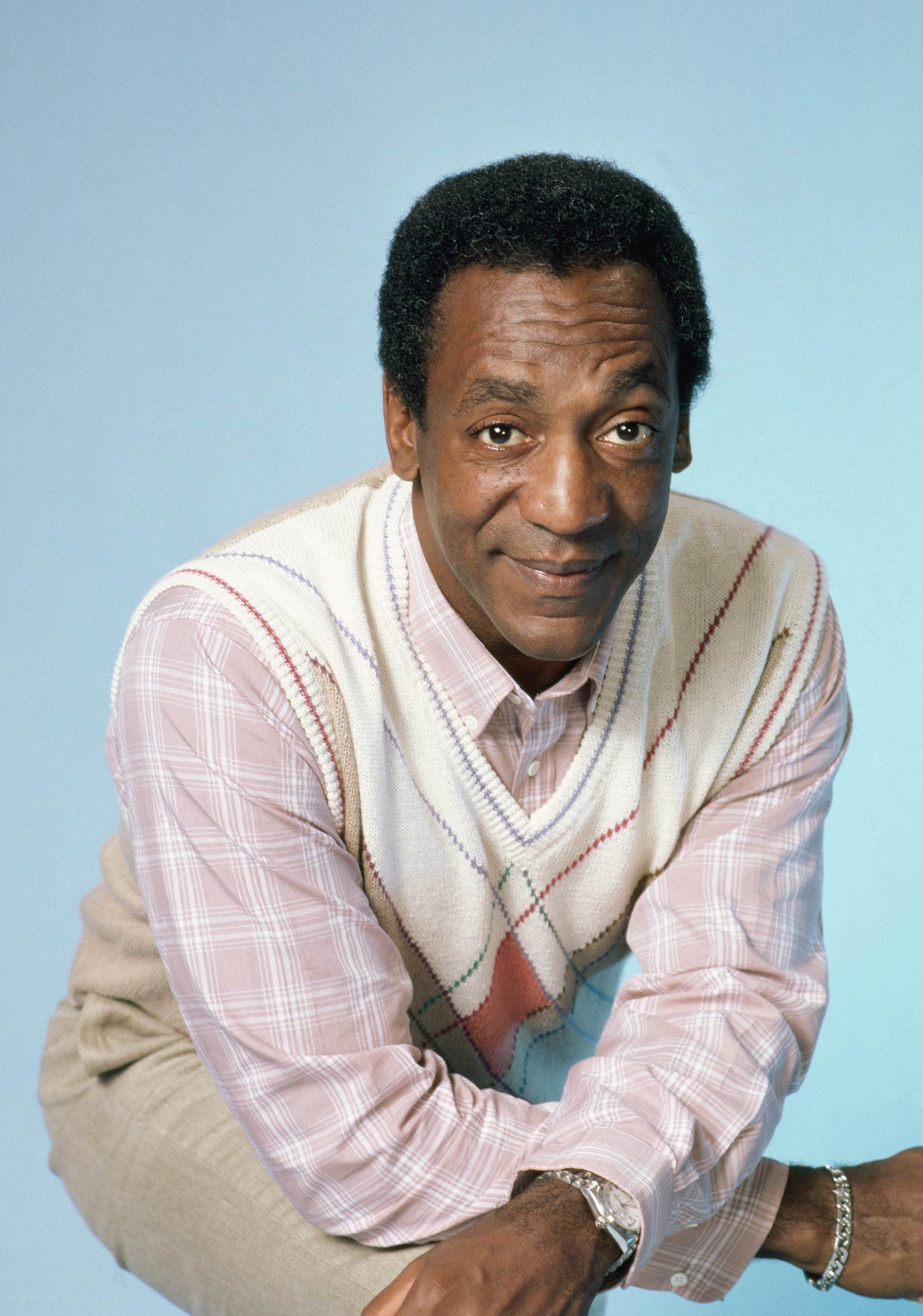

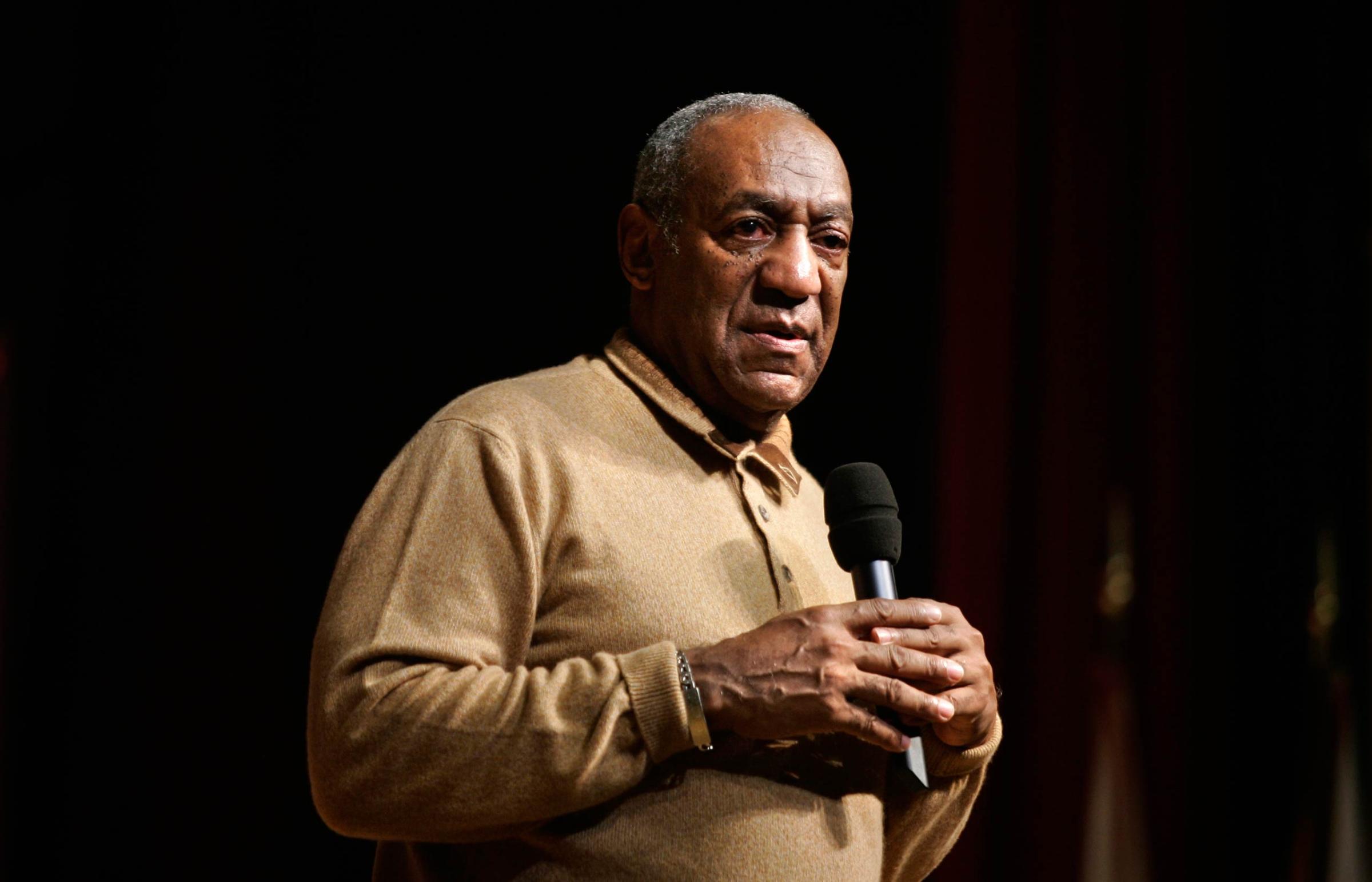

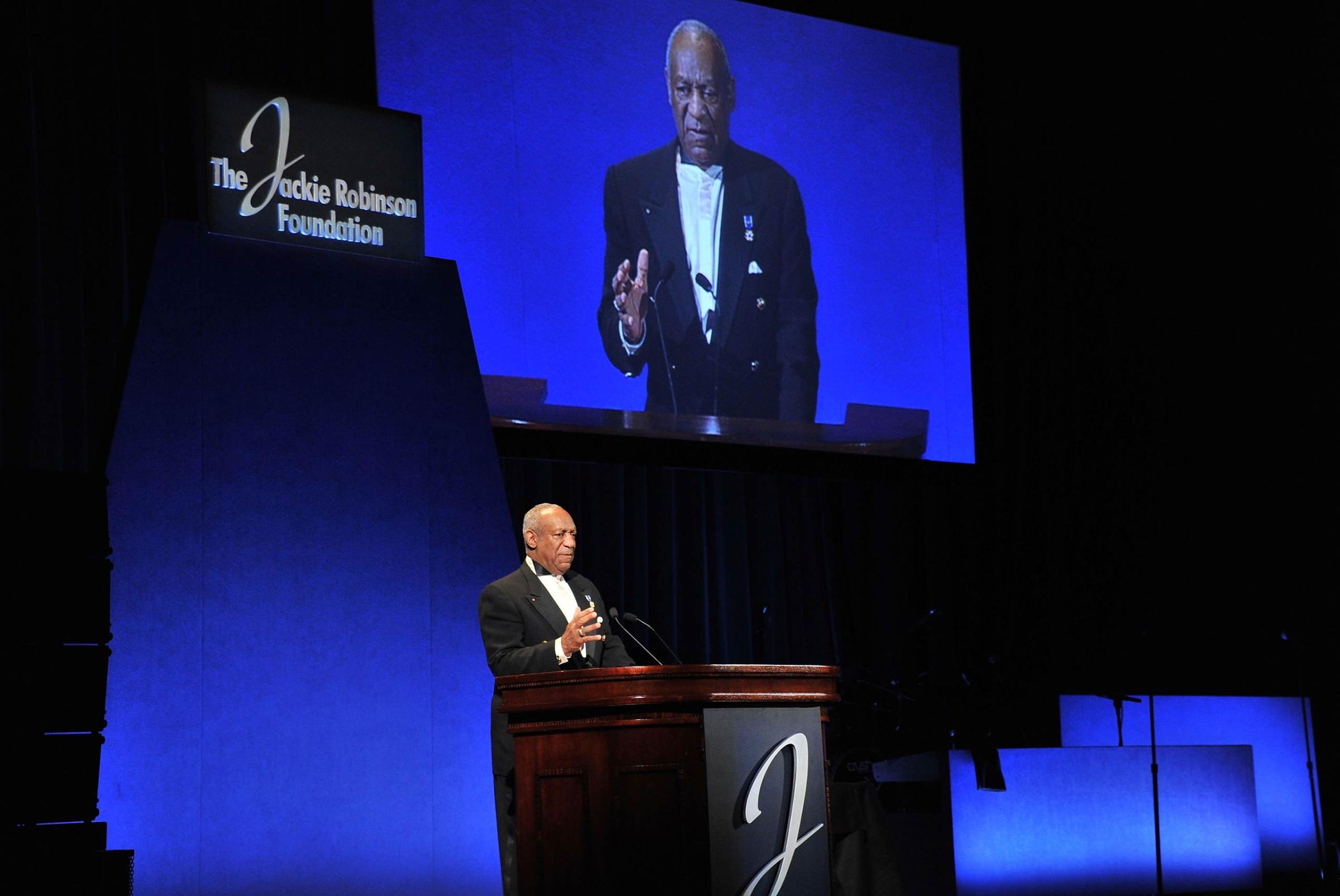

Bill Cosby’s Public Life in Photos

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com