My sister stood around the corner and deliberately out of sight, curious to see what her then-14-month-old son, Chaim, was up to. He sat on the kitchen floor, legs spread around the dog’s dish. With a devilish smile, Chaim looked around a couple of times before plunging his bare hands into the bowl and extending it as an offering to his closest friend, Sammy, the family’s poodle mix.

My sister, Sheryl, couldn’t have been more delighted. No, she wasn’t fond of Chaim boy-handling the Alpo. But the idea that Chaim knew he was doing something wrong and took precautions to avoid being caught showed logic and reasoning skills that she hadn’t before seen or anticipated. After all, before a baby with Down syndrome is born, doctors warn the expectant parents that a dire, sad, dependent life may lie ahead.

“I remember thinking, ‘Boy, there’s a lot more going on in his brain than I thought,’” says my sister, Sheryl Zellis. “When you see a child sneaking to do something, it kind of heartens you.”

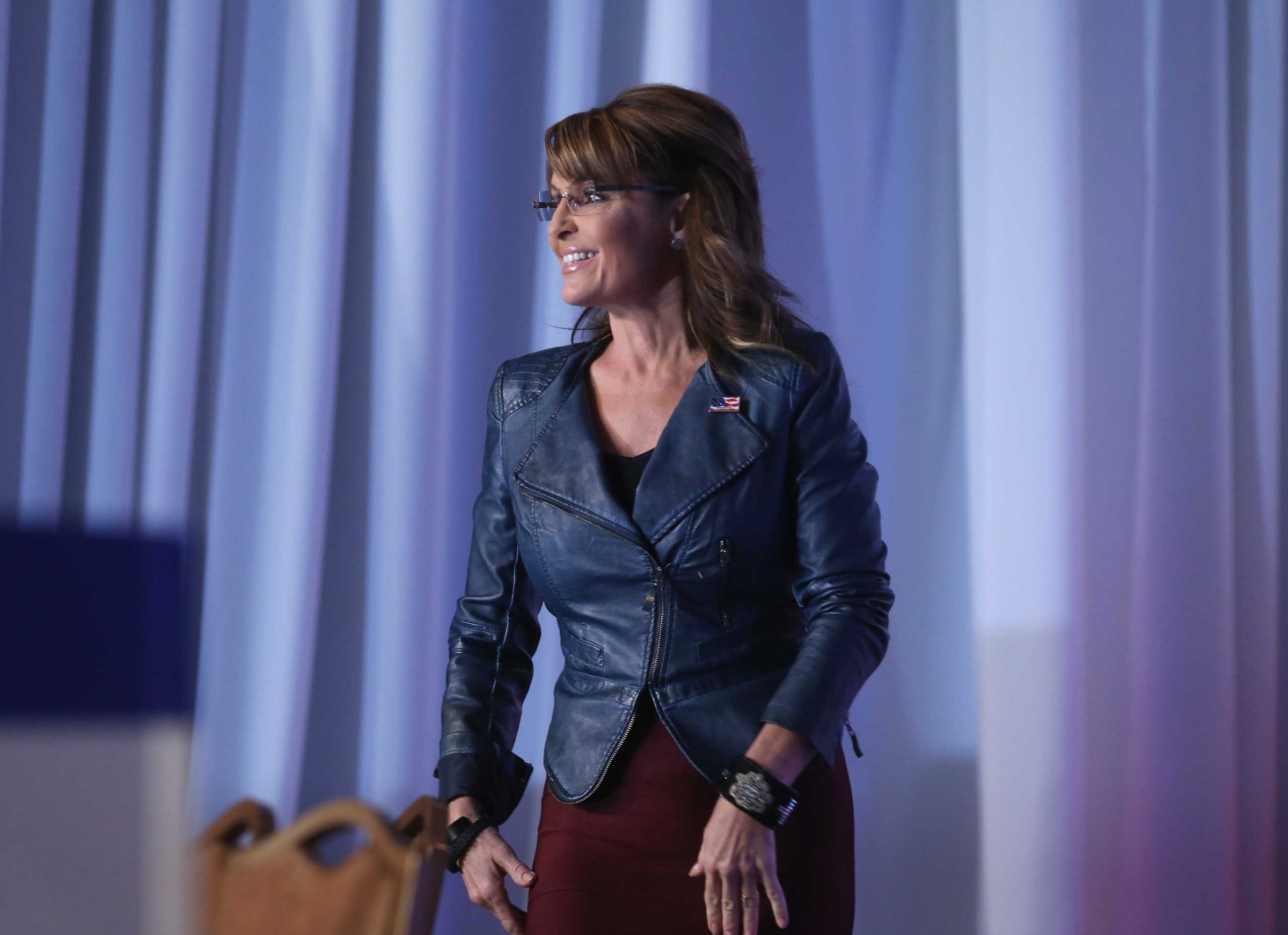

This is the side of those controversial images—the ones that former GOP vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin posted of her son, Trig, standing on his dog—that my sister and other parents of children like Trig and Chaim say is overlooked. Even Palin, confronted by Savannah Guthrie on Today this week, understood that standing on small animals is generally not a good habit. But for a woman hoping that her 6-year-old will exceed the low expectations placed on him by both doctors and the rest of society, the fact that Trig figured out a solution to any problem is a tremendous triumph.

I admit I didn’t get that right away, either. Yes, I cringed, too, at the photos Palin proclaimed to be a terrific example of how we all should live in the year ahead. But then I saw a Facebook post from a close friend–an unimpeachable animal lover and inveterate political liberal—who is also raising a boy with Down syndrome. Along with one of the most adorable photos ever taken of a 7-year-old with his dog, Cindy Glover of Boynton Beach, Fla., wrote:

“I’m finding myself in the very odd and somewhat disorienting position of defending Sarah Palin. My 35-pound son sits on our 82-pound Golden Retriever all the time (and, yes, he has stood on her to reach something). They have a beautiful bond, and I have great confidence that Ginny will simply get up and move if she objects. It feels weird to say it, but in the Palin/PETA smackdown, I’m going to have to side with Palin this time.”

There hasn’t been much notable scientific literature on the relationship between dogs and children with Down syndrome—I found just one study about a program that uses dogs to help special needs children learn to read—but anecdotal examples abound. This week, for instance, a mother asked on one of my sister’s Facebook forums for parents of Down kids whether getting a puppy was good for her 18-month-old. She was clobbered with replies from parents offering their tales of how key a relationship to a canine has been to helping their children.

Both Sheryl and Cindy have their own examples. Sheryl used Chaim’s fascination with Sammy to teach him to roll, sit up, and cruise—all motor skill functions that Down children can have great trouble with and can take months or years longer than typical kids to master. Walking the dog “alone” around the house on a leash gives Chaim a sense that he’s accomplished something on his own, which builds his confidence. Dylan, who is generally nonverbal, will nonetheless “sing” to his dog with a little microphone. When he comforted Ginny last year as fireworks spooked her, his mother took it as a remarkable and unprecedented display of empathy.

Certainly there are other ways to encourage movement, interpersonal skills, and problem-solving thought for kids like this, “but animals are so much fun to children,” Sheryl says. “Children with Down syndrome are very visual in how they learn, and animals are very visual and dynamic, as opposed to a toy, which always does the same thing.”

That Trig Palin chose to stand on Jill Hadassah–quite a name for a dog, indeed–was decried by many as animal abuse, particularly because his famous lightning rod of a huntress mother touted it with pride but no empathy for the dog. This is, unfortunately, how she’s become conditioned to react to any negative feedback, to become defensive and sharp-elbowed and treat it like any number of other liberal-versus-conservative skirmishes.

For the sake of other parents of Down syndrome kids, though, she might consider another approach. Her mothering of Trig is, by far, the most admired, most humanizing part of her biography to many, the one thing even her fiercest critics respect. She may not feel she owes anyone any explanations, but she did anoint herself as an advocate for children with special needs at the 2008 Republican National Convention in her first major national speech. The role of advocates, first and foremost, is to educate people so they will understand and then support your cause.

Those photos show an intrinsic trust between the child and his dog that implies so much about Trig’s relationship with Jill Hadassah. Sheryl worries it’s not a great habit to encourage, if only because Trig might try to stand on someone else’s, less amenable dog and get hurt in myriad ways. But surely Palin knows that, too.

Palin has that gigantic microphone. It comes with a ton of drawbacks, especially when it comes to public reaction to her family. But this is a teachable moment she can seize. It probably won’t quell PETA’s ire, but that’s the fringe anyway. The rest of us are open to knowing more.

Steve Friess is an Ann Arbor, Mich.-based freelance writer and former senior writer covering technology for Politico.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com