Richard Nixon was a lunar buzzkill—but at least he was honest about it. During the early years of the space program, Nixon held no political office, which put him on the sidelines for all of the one-man Mercury flights and two-man Gemini flights, as well as the first two flights of the Apollo program. But he assumed the presidency in January of 1969 and was thus the one who got to spike the football in July of that year, phoning the moon from the Oval Office to congratulate the Apollo 11 crew on their historic lunar landing.

Not long afterward, the same President canceled the Apollo program—though he held off on making his announcement until after his reelection in 1972 was assured.

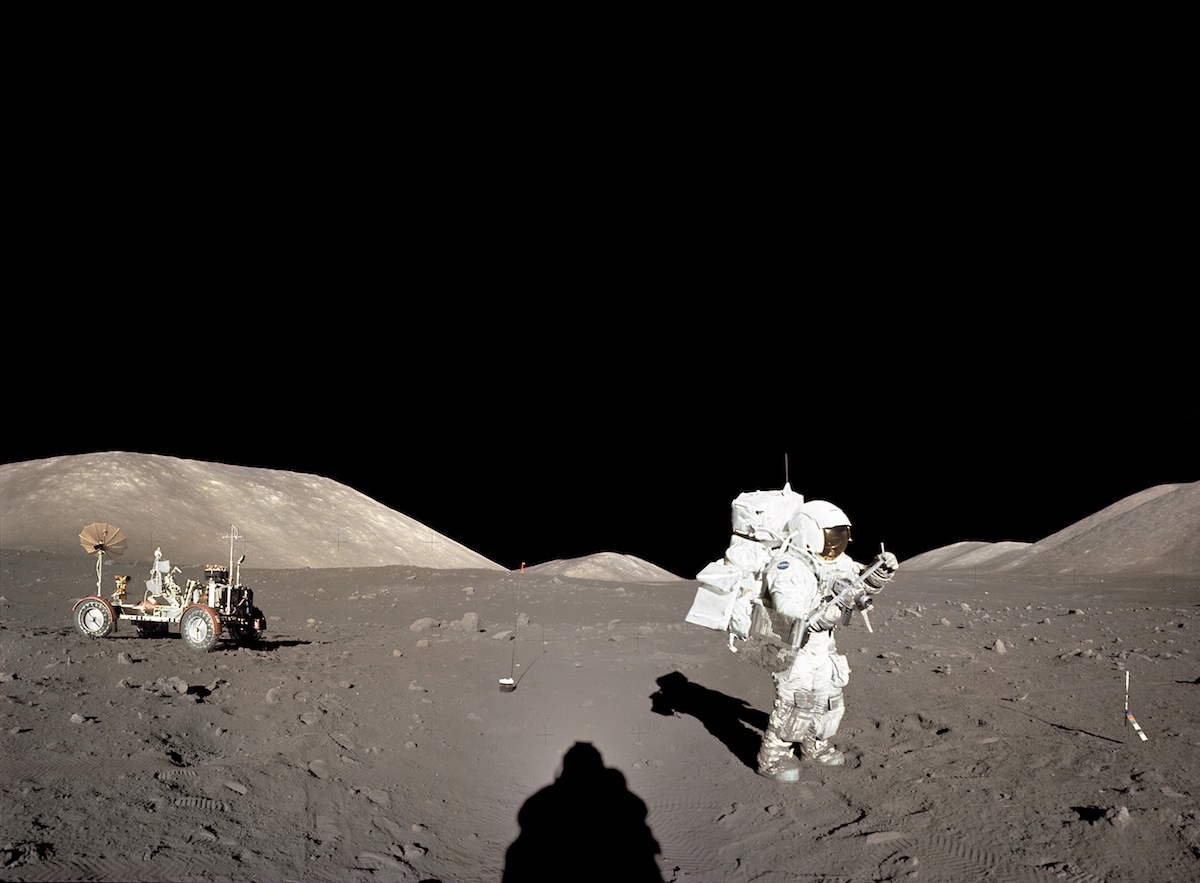

During the final lunar landing mission—Apollo 17, which left Earth on Dec. 7, 1972 and reached the moon on Dec. 11—Nixon was candid about what the future held for America’s exploratory ambitions, and it was not good. “This may be the last time in this century that men will walk on the moon,” he said in a formal pronouncement.

As it turned out, things have been even bleaker than that. It’s been 42 years since Apollo 17 commander Gene Cernan climbed up the ladder of his lunar module, leaving the final human footprint in a patch of lunar soil. TIME’s coverage of the mission provides not only an account of the events, but a sense—unintended at the time—of just how long ago they unfolded. There are the quotation marks that the editors thought should accompany the mention of a black hole, since really, how many people had actually heard of such a thing back then? There was, predictably, the gender bias in the language—with rhapsodic references to man’s urge to explore, man standing on the threshold of the universe. It may be silly to scold long-ago writers for such usage now—but that’s not to say that, two generations on, it doesn’t sound awfully odd.

Over the course of those generations, we’ve made at least one feint at going back to the moon. In 2004, then-President George W. Bush announced a new NASA initiative to return Americans to the lunar surface by 2020. But President Obama scrapped the plan and replaced it with, well, no one is quite certain. There’s a lot of talk about capturing a small asteroid and placing it in lunar orbit so that astronauts can visit it—a mission that is either intriguing, implausible or flat-out risible, depending on whom you talk to. And Mars is on the agenda too—sort of, kind of, sometime in the 2030s.

But the moon, for the moment, is off America’s radar—and we’re the poorer for it. There were nine manned lunar missions over the course of three and a half glorious years, and half a dozen of them landed. That makes six small sites on an alien world that bear human tracks and scratchings—and none at all on the the far side of that world, a side no human but the 24 men who have orbited the moon have seen with their own eyes.

We tell ourselves that we’ve explored the moon, and we have—after a fashion. But only in the sense that Columbus and Balboa explored the Americas when they trod a bit of continental soil. We went much further then; we could—and we should—go much further now. In the meantime, TIME’s coverage of the final time we reached for—and seized—the moon provides a reminder of how good such unashamed ambition feels.

Read a 1973 essay reflecting on the “last of the moon men,” here in the TIME Vault: God, Man and Apollo

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com