It has come down to this in the Ferguson shooting of Michael Brown: none of the evidence produced a clear enough picture of inappropriate behavior by Officer Darren Wilson. Indeed, the preponderance of forensic and eyewitness testimony suggests that Wilson was acting in self-defense against a violent perpetrator. But the eyewitness testimony is muddled, even among the local residents who supported Wilson’s version of the story. It is amazing how fast violence happens, how hard it is to remember events accurately. And so the grand jury couldn’t say–wasn’t asked to say–what actually happened on August 9 in Ferguson.

VOTE: Should the Ferguson Protestors Be TIME’s Person of the Year?

It is probable that a public jury trial would have a tough time establishing Wilson’s guilt or innocence beyond a reasonable doubt. The question is, do Michael Brown’s parents–and the rest of us–deserve to have the facts laid out, the case against Wilson argued in a court of law? Undoubtedly, there will be such a case–a federal case or a civil case, brought by the parents. But a grand jury indictment, even on a lesser charge like manslaughter, would have lent appropriate seriousness to a contested, foggy situation. It would have indicated, at the very least, that the evidence wasn’t dispositive and the situation required further public attention.

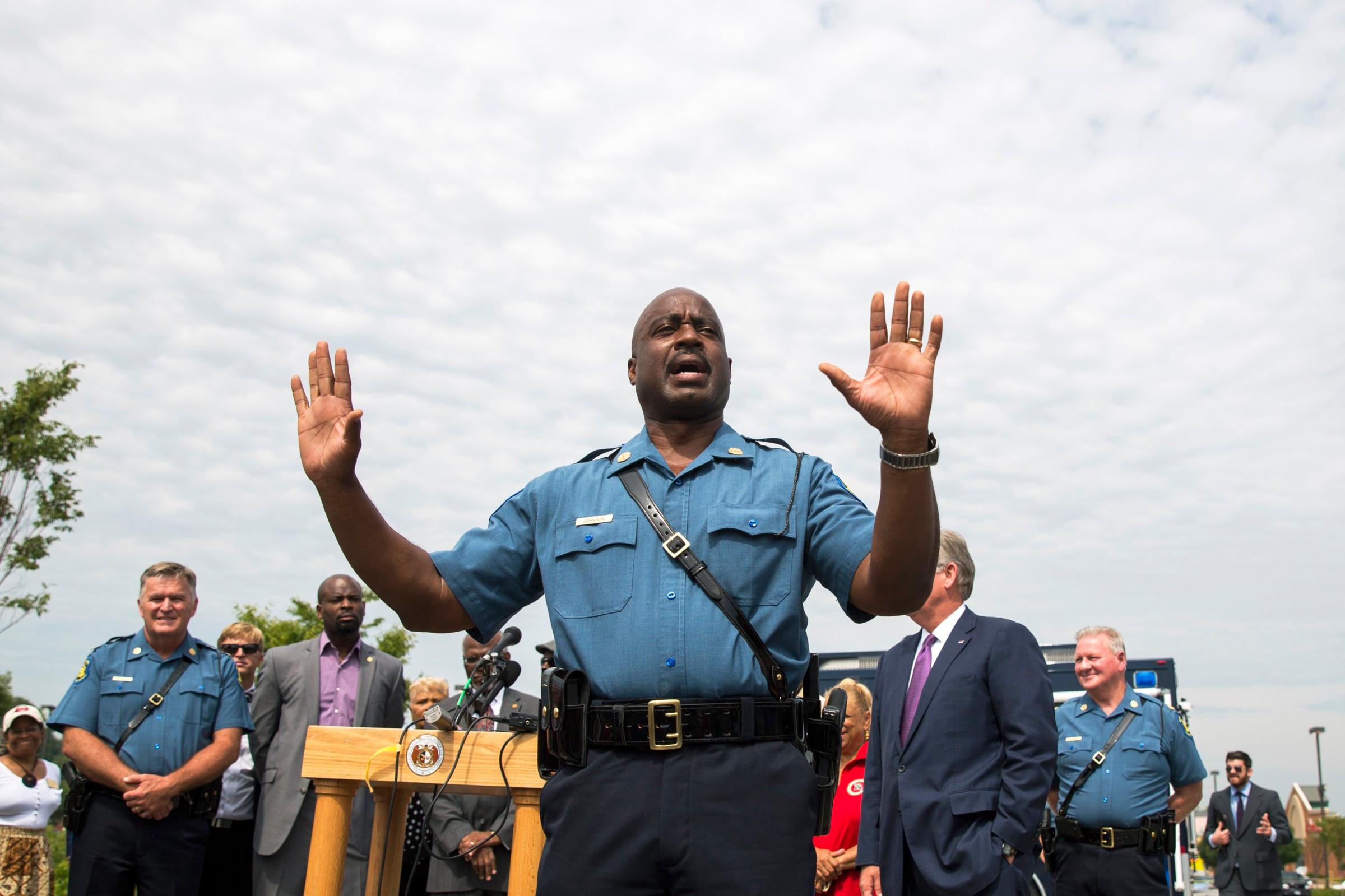

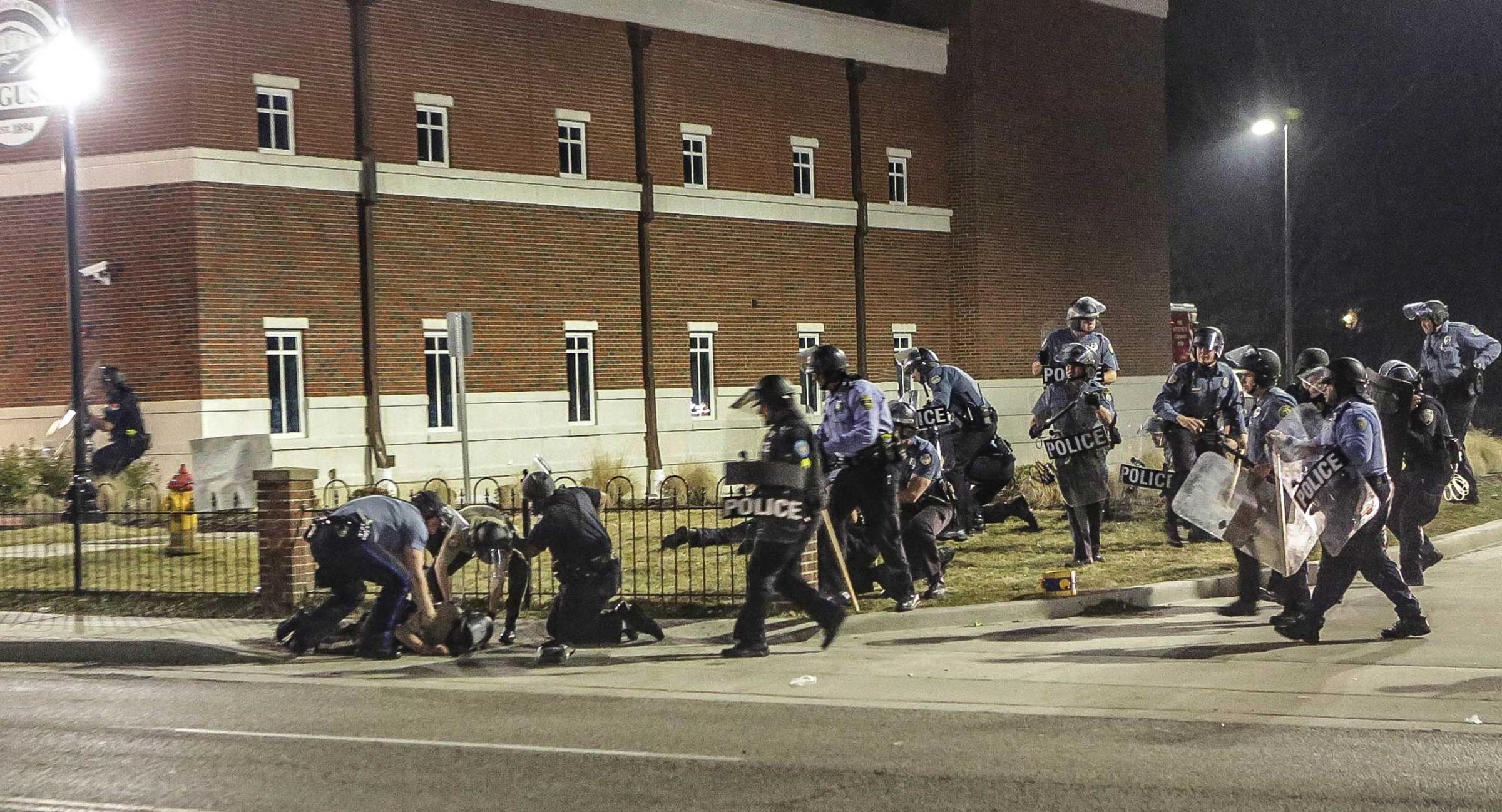

Several things are absolutely clear, though. The authorities in Missouri, from Ferguson to St. Louis County to the governor’s office, have bungled this case from the start. That Michael Brown’s body was allowed to lie in the street for four hours is inexcusable. That crucial evidence–Wilson’s gun–was not dusted for prints is mystifying and incompetent. And then there was the Monday spectacle of a verdict reached, but not announced until after dark. Sheer idiocy.

See 23 Key Moments From Ferguson

But there can no longer be a question that the initial accounts of the case were fraudulent. Michael Brown was not a gentle giant. He was not shot in the back. There was a scuffle of some sort between Brown and Wilson, perhaps with Brown trying to gain control of the police officer’s gun. There was, apparently, at least one shot fired at close range. Brown ran away, then turned and charged the officer.

Again, as I wrote a few weeks ago, Wilson’s actions may have been justifiable under the law in Missouri, but he is not entirely exonerated: the death would have been preventable if he had been better trained. Still, you can’t indict Wilson for not abiding by training he didn’t receive. And you can’t elide the facts of the case. Wilson clearly panicked. He thought his life was in danger. He killed a young man. He should have to defend these actions publicly, under the fierce pressure of cross-examination.

There will now be still more calls for a discussion about race in America. But that conversation can not simply be about white guilt or prejudice. The latter certainly does exist; it exists overwhelmingly, disgracefully. But the assumptions that lead police, and bodega owners, to racial profiling are real–and those must be discussed, too. Liberals have avoided this conversation for 50 years, since crime rates exploded in the 1960s. And by doing so, they have done a real disservice to the disproportionate number of crime victims who are African-Americans, urban and poor. Poverty is no excuse for criminality. People who commit crimes are perpetrators, not victims. Indeed, blaming poverty for criminality is an insult to the vast majority of poor blacks who play by the rules–graduate from high school or college, find a job, are responsible parents–and have improved their lives as a result. As the President said, you can’t gainsay the fact that there has been enormous progress over the past 40 years…with more to come, as a new generation of polychromatic, unprejudiced young people take charge.

Back in the 1980s, my wife and I lived in a mostly-black neighborhood in New York. Our neighbors were placed in an impossible position: they were infuriated that many of the police who patrolled (or, more often, failed to patrol) our streets treated them as if they were criminals, but they also were terrified of, and infuriated by, the criminals who made it a life-threatening challenge to go down to the corner for a quart of milk. We had some real conversations in those days–about crime, about the double-edged sword of affirmative action, about the hilariously stupid racial assumptions they encountered in the city. Some of our neighbors were public employees; others weren’t and were pissed off about the level of service they were receiving. There were intense conversations about whether it was “racist” to fire incompetents on the public payroll. I miss those conversations. They required a certain amount of candor and subtlety. They would have been impossible for ideologues, because the reality on our block defied any ideology. And they probably would have been impossible in public, since it was very hard for our neighbors to criticize young black men who had grown up in anger-infusing chaos.

It is sad, but inevitable, that there will be two conversations about Ferguson. One will be public, one will be private. The public conversation will be dominated by rant, oversimplification and guilt-mongering. The private conversation will be unspeakable in segments of the white, Asian and Latino communities. If my experience in the 1980s is any guide, the conversations in the black community will be more reasonable, marked by anger, pain, embarrassment and the difficulties of dealing with kids like Michael Brown. It’s a national tragedy that we can’t seem to have that conversation in public, that political correctness stands directly athwart honesty in this republic of free speech.

Should the Ferguson Protestors Be TIME’s Person of the Year? Vote Below for #TIMEPOY

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com