Correction appended, Nov. 24, 2014, 5:49 p.m.

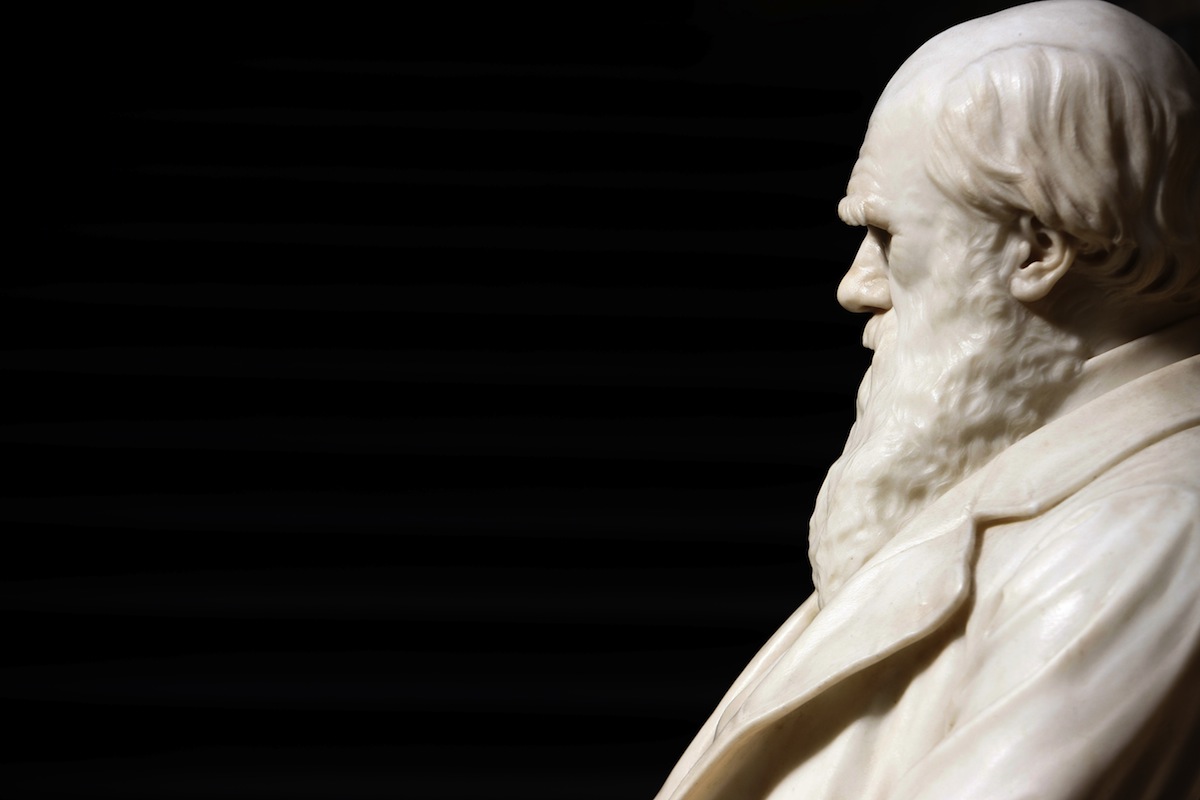

Time was, “Darwin” was just a guy’s name. It was not a noun (Darwinism) or an adjective (Darwinian). And it certainly wasn’t a flash point for debate between folks who prefer a Scriptural view of the history of life and those who take a more scientific approach. That started to change 155 years ago today, on Nov. 24, 1859, when Charles Darwin’s seminal work—On the Origin of Species—was published.

Darwin knew that by supporting an empirical theory of evolution as opposed to the Biblical account of Creation he was asking for trouble. Two weeks before the book’s publication, he sent letters to 11 prominent scientists of his day, asking for their support—or at least their forbearance—and acknowledging that for some of them, that would not be easy. To the celebrated French botanist Alphonse de Candolle he wrote:

Lord, how savage you will be, if you read it, and how you will long to crucify me alive! I fear it will produce no other effect on you; but if it should stagger you in ever so slight a degree, in this case, I am fully convinced that you will become, year after year, less fixed in your belief in the immutability of species.

And to American Asa Gray, another botanist, he conceded:

Let me add I fully admit that there are very many difficulties not satisfactorily explained by my theory of descent with modification, but I cannot possibly believe that a false theory would explain so many classes of facts as I think it certainly does explain.

But the whirlwind came anyway. Speaking of Darwin in 1860, the Bishop of Oxford asked: “Was it through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed his descent from a monkey?” The battle raged in the U.S. in the summer of 1925, with the trial of John Scopes, a substitute school teacher charged with violating a Tennessee statute forbidding the teaching of evolution in schools.

But Darwin and his theory of evolution endured, so much so that Nov. 24 is now recognized as Evolution Day. As if serendipity and circumstance were conspiring to validate that decision, it was on another Nov. 24, in 1974, that the fossilized remains of Lucy, the australopithecus who did so much to fill in a major gap in human evolution, were found in Ethiopia.

In honor of Lucy and Evolution Day and Darwin himself, check out TIME’s coverage of the florid anti-evolution closing argument of prosecuting attorney and three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan during the Scopes trial, as quoted in the magazine’s Aug. 10, 1925 issue:

“Darwin suggested two laws, sexual selection and natural selection. Sexual selection has been laughed out of the class room, and natural selection is being abandoned, and no new explanation is satisfactory even to scientists. Some of the more rash advocates of Evolution are wont to say that Evolution is as firmly established as the law of gravitation or the Copernician theory.

“The absurdity of such a claim is apparent when we remember that any one can prove the law of gravitation by throwing a weight into the air and that any one can prove the roundness of the earth by going around it, while no one can prove Evolution to be true in any way whatever.”

Bryan died mere days after the trial ended but, as the historical record shows, his strenuous efforts paid off—sort of. Scopes was duly convicted. His sentence for teaching what most of the world now accepts as science: $100.

Read the full text of that story, free of charge, here in the TIME archives, or in its original format, in the TIME Vault: Dixit

Correction: The original version of this article misstated the date of Darwin Day. Darwin Day is typically celebrated on February 12.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com