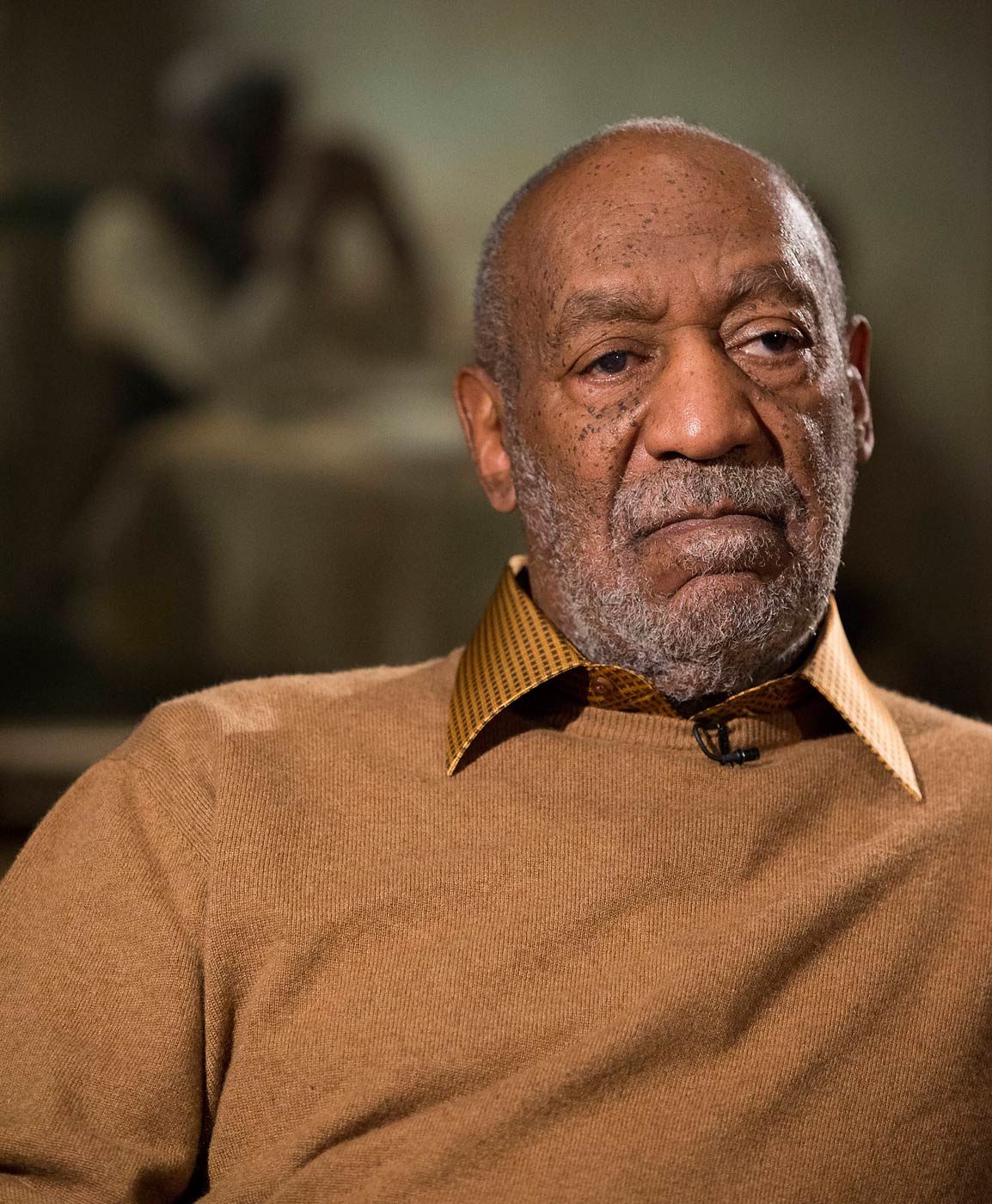

Mark Whitaker wants you to purchase his biography of Bill Cosby. As a biographer myself, I want you to purchase biographies galore, including those I write. But despite my book buying habit, I will refrain from owning Cosby: His Life and Times.

Whitaker made a decision to exclude allegations from at least thirteen women that Cosby sexually assaulted them—he says their allegations failed to meet his standards of proof. Biographers must make difficult decisions in every paragraph they publish, because reputations ought to be handled with care. Whitaker’s decision, though, should not have been difficult. As an experienced journalist, he made a bad call.

In an interview yesterday, Whitaker mentioned being unable to confirm the rape allegations independent of the victims’ accounts, as there were no definitive court findings regarding the allegations. “What you eventually learn about everything related to these allegations, and how you think that should figure in your ultimate judgment of Bill Cosby has to be weighed—and should be weighed—in the balance with a lot of the stuff I reported in the book more thoroughly than anybody else,” he said. It’s hard to consider Whitaker a reliable reporter considering what he has left out; his standards are not only unrealistic, but also unwise and irresponsible for a biographer who wants to present a complete picture of his subject.

Biographers know that circumstantial evidence is as valid—and perhaps as necessary—for inclusion as direct evidence, as long as the circumstantial evidence accumulates at a certain level. Rarely do rapists assault their victims in front of witnesses. Is Whitaker suggesting that all biographers ignore detailed rape charges issued by women—ones who identify themselves, no less—against iconic, influential, wealthy men because nobody else was in the room?

Many of the alleged violent encounters between Cosby and various women occurred more than a decade before publication of Whitaker’s biography. In 2005, Andrea Constand filed a lawsuit in a Philadelphia court; on the heels of her charges, twelve other women came forward, ready to testify on behalf of the plaintiff that they had been sexually assaulted by Cosby. The then-prosecutor decided there was not sufficient evidence to criminally charge Cosby—”I remember thinking that he probably did do something inappropriate,” the lawyer recently said, “But thinking that and being able to prove it are two different things”—but Cosby settled a civil suit with Constand.

In 2006, journalist Robert Huber published a painstakingly detailed article, “Dr. Huxtable and Mr. Hyde,” in Philadelphia magazine about the litigation. Other journalists have reported responsibly about the allegations. If Whitaker had at minimum simply mentioned the findings of those journalists in his book, he might have escaped the criticism now aimed at him.

Yes, many potential and actual readers of Whitaker’s biography idolize Cosby. And yes, some of them—a tiny minority, I believe—prefer sanitized biography. Hagiography, if you will. No drunken bouts, no snorting cocaine, and certainly nothing involving sexual acts—especially rape.

But responsible biographers never set out to produce hagiography or pathography. They set out to find truth. That may sound inflated; after all, many of us do not really know our parents, our spouses, our children, our cousins, our social friends. If those folks surprise us, for better or for worse, can we ever know a stranger? Armand Hammer was elderly but alive while I researched his biography during the 1980s. He expressed hostility from the start, threatened to sue me, and did indeed sue me and the publisher. I never met him. So how can I presume to know the truth about his controversial life?

The answer is not so complicated. Pieces of the truth are scattered around the world—in official government documents at the city, county, state and federal levels; in business correspondence; in personal letters; in interviews with relatives and friends and enemies, current and former. I knew Hammer’s son Julian had personal problems, but I was not planning to provide lots of detail to readers. Then my research turned up evidence that Julian had killed a man in college. At trial, he won an acquittal, possibly because of influence exercised by his father in relation to the prosecutor and one or more of the jurors. I included the death in my book. First, all individuals, including Armand Hammer, who choose to become parents should be evaluated in that role. Second, the possibility of tampering with the criminal justice system certainly allows for a more nuanced understanding of the alleged tamperer’s character.

I liken the information-gathering process to vacuuming a house—everything finds its way into the vacuum bag. When the bag is filled, the biographer examines the contents, deciding what to place in the book and what to omit. The decision-making might seem filled with conundrums, but it should be clear-cut if the overriding purpose is to illuminate an individual’s character on the path to truth. That overriding purpose should be the same whether the subject is cooperating with the biographer, as Cosby did with Whitaker, or whether the subject is hostile, as Hammer was with me. And access should not equal acquiescence.

At minimum, Whitaker should have decided that the multiple allegations of sexual assault affected Cosby’s own life so deeply that they needed to be included in the book. Based on his evaluation of the evidence, Whitaker could have told readers that he doubted the allegations. Or he could have told readers that the allegations existed—an objective fact. Whatever Whitaker concluded about the evidence, he needed to tell readers how Cosby reacted, and why he might have reacted as he did. Instead, Whitaker participated in a biographical cover-up—a classic lie of omission. That is never an acceptable decision for the chronicler of somebody else’s life.

Steve Weinberg, Professor Emeritus at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, has published biographies of Armand Hammer and Ida Tarbell, plus written a book about the craft of biography, Telling the Untold Story. He is a founding member of Biographers International Organization (BIO). Weinberg is currently researching a biography of Garry Trudeau.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com