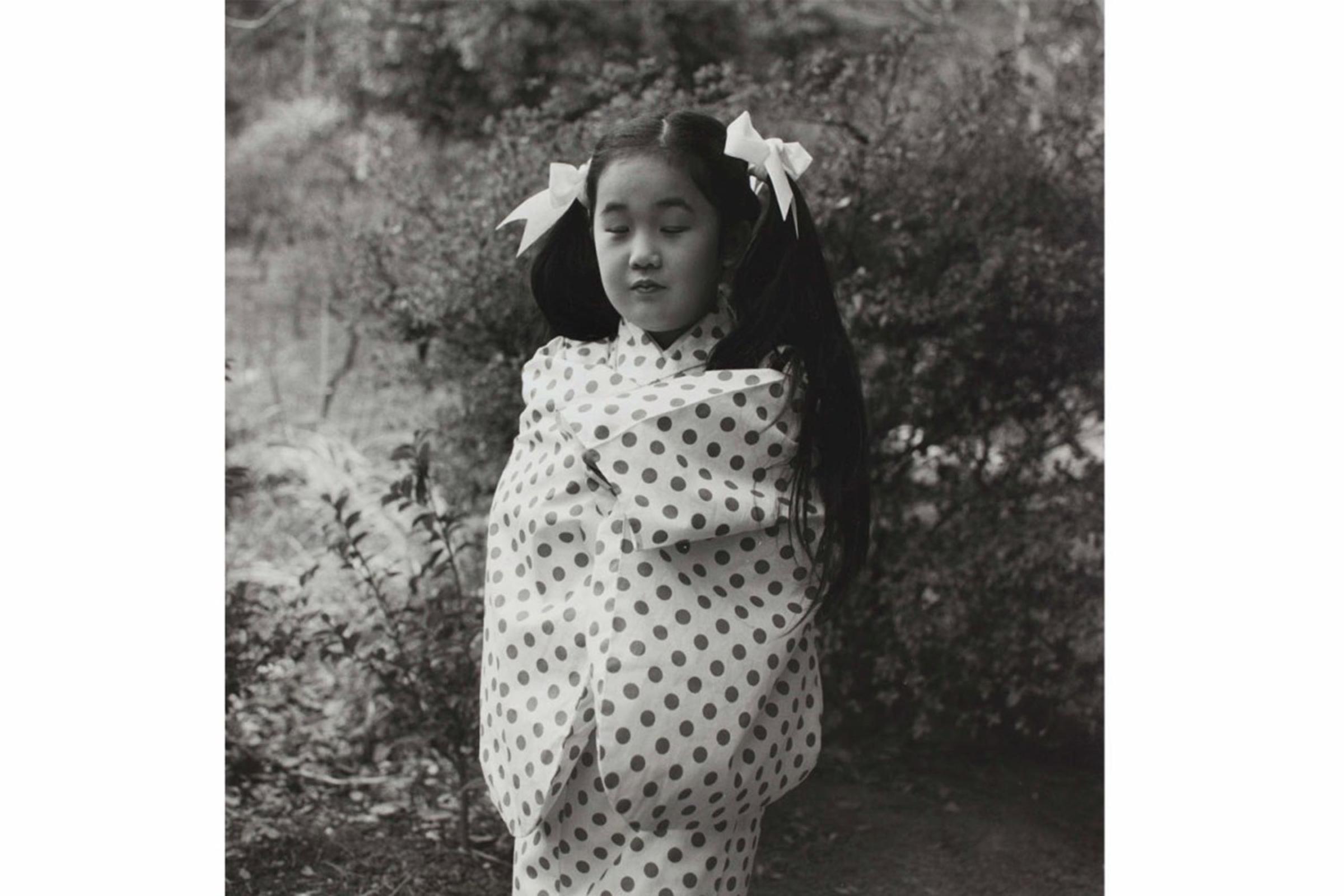

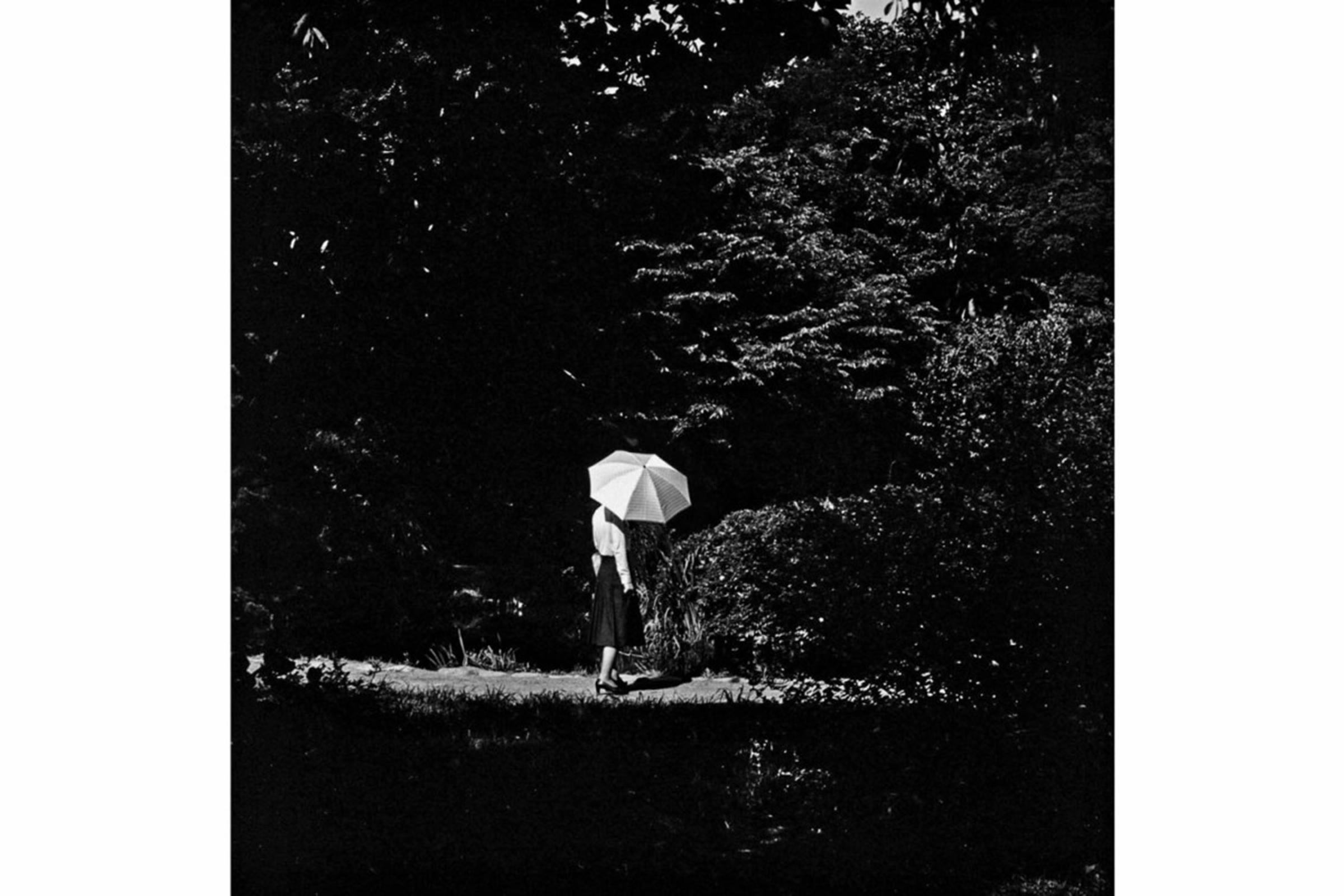

Seemingly oblivious to the presence of the camera, a middle-aged woman sits on a bench, shaded by her umbrella, she takes in the surroundings of Hachimantai Mountain in northern Japan. Nearby, steam rises from hot springs, adding a sense of drama. On the opposite side of the bench sits a young man dressed in black, his back turned to the lens. He gives a sideways glance, almost as if he knows he is being watched. The two have inadvertently become actors in a form of theater of the everyday documented by the photographer Issei Suda.

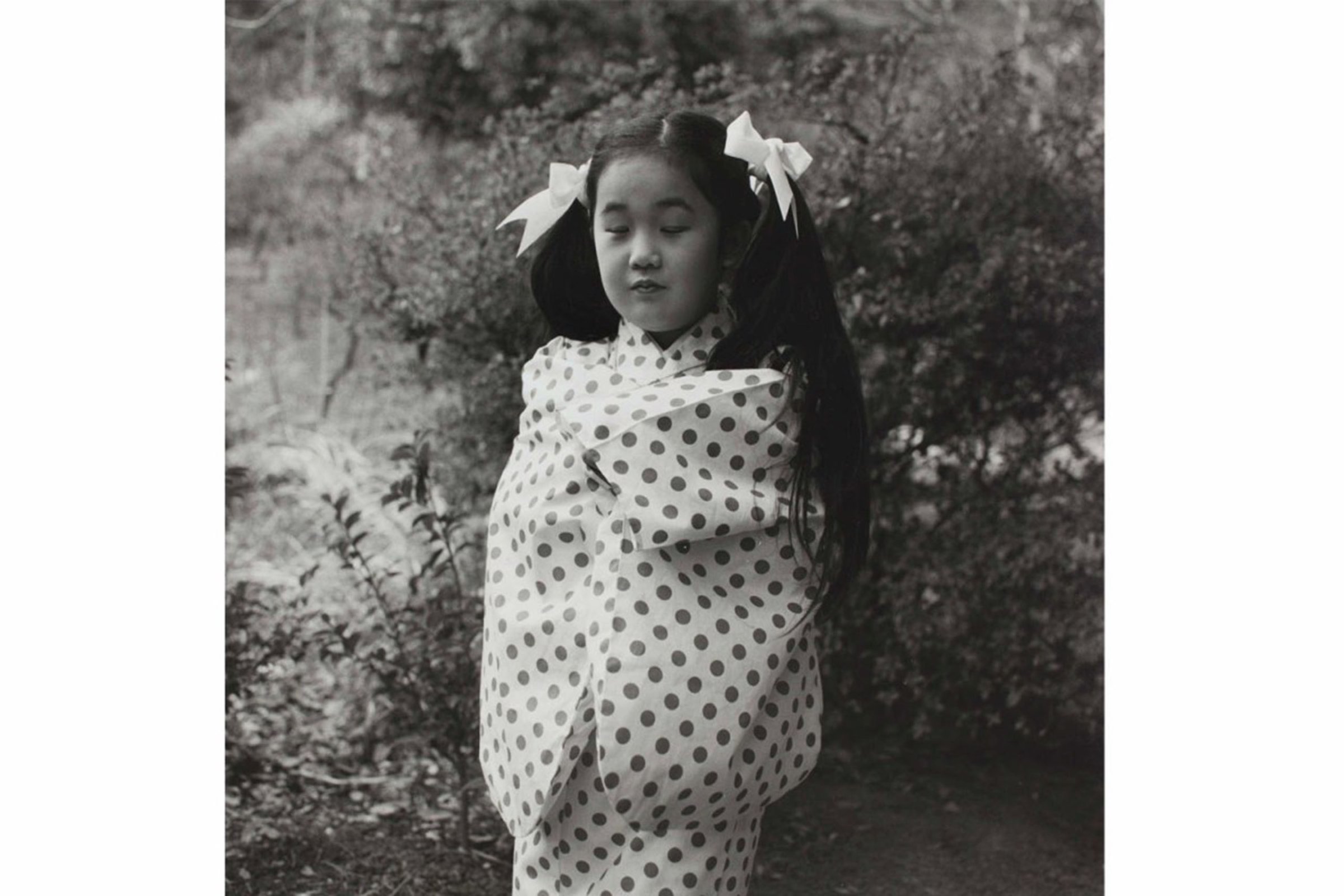

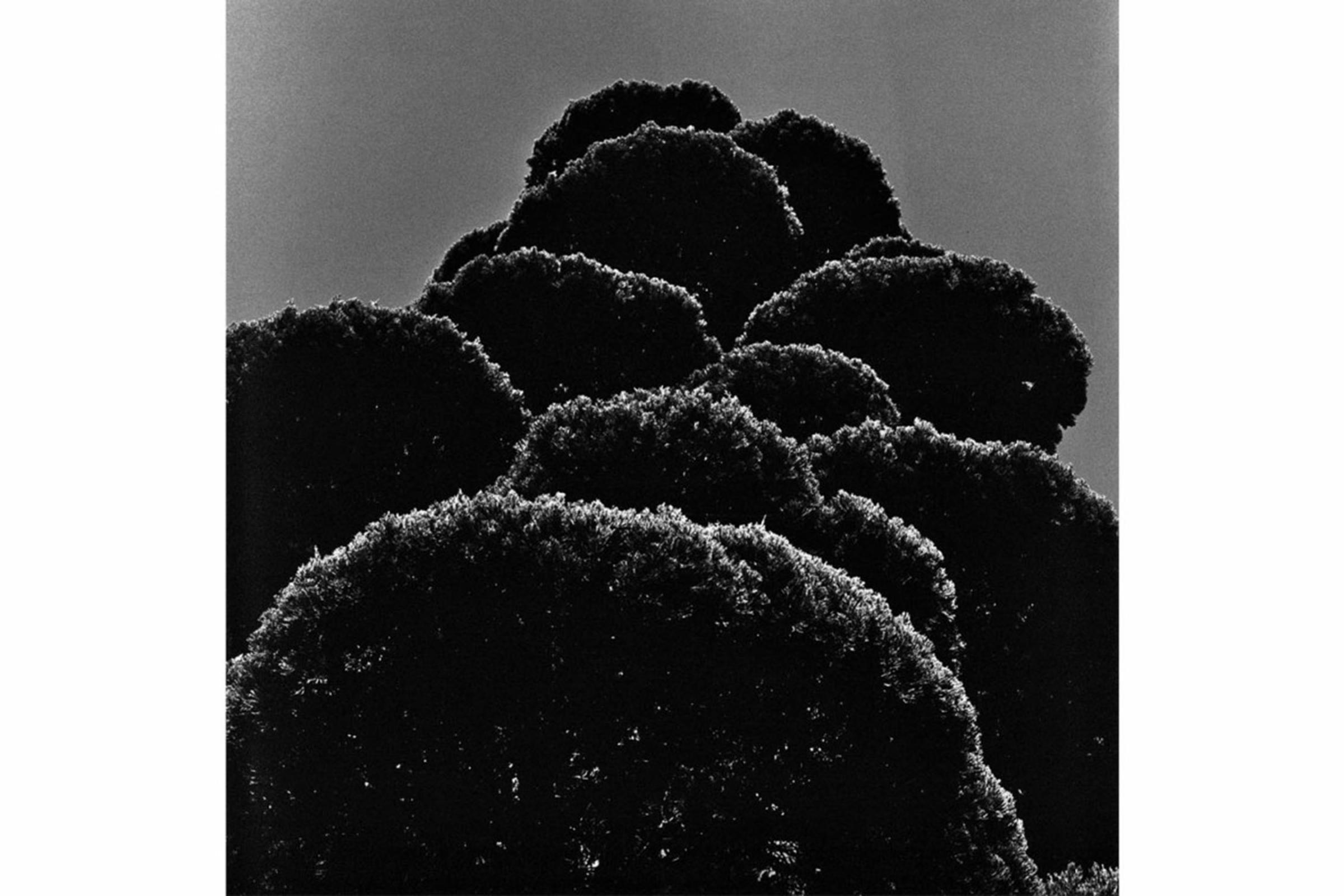

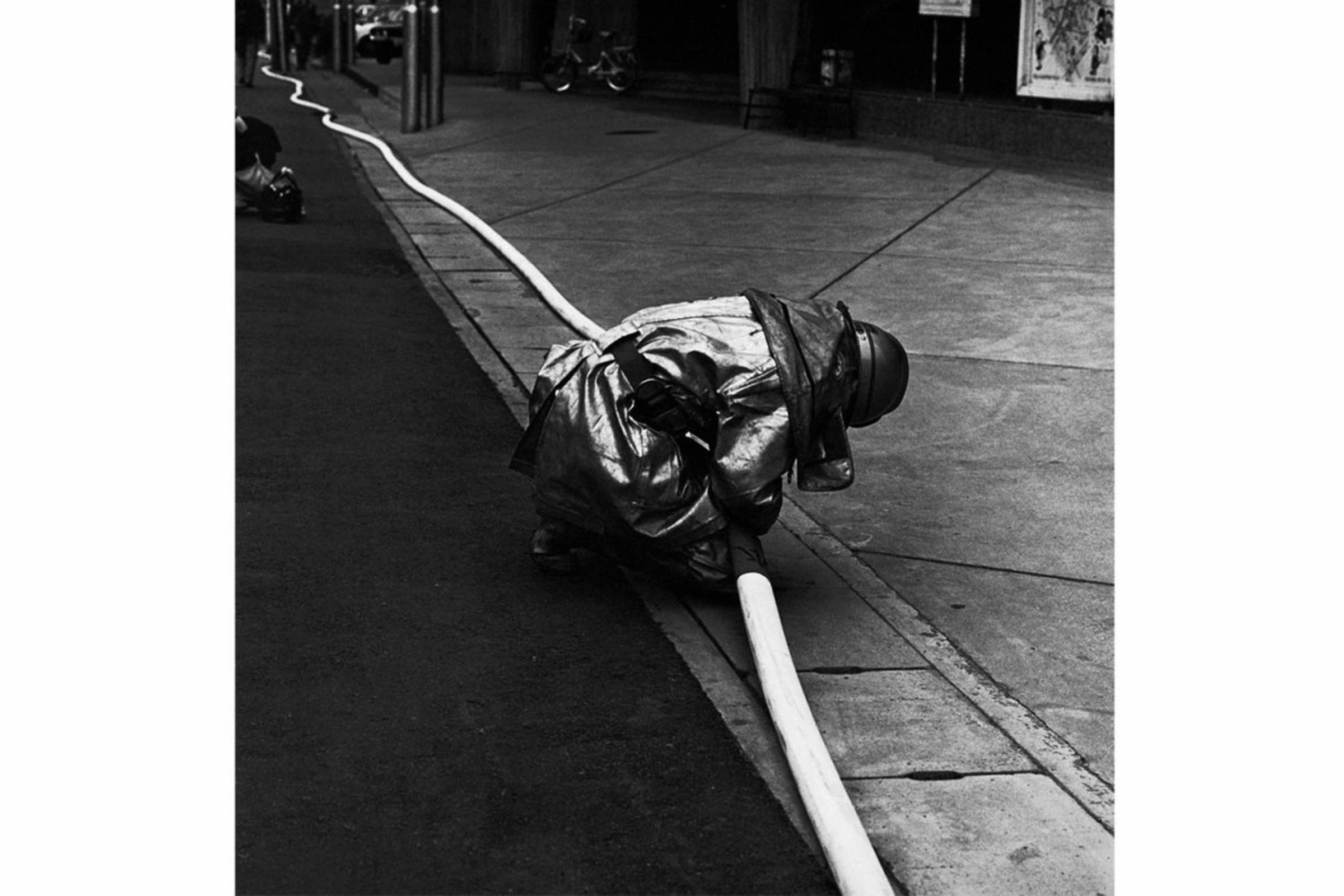

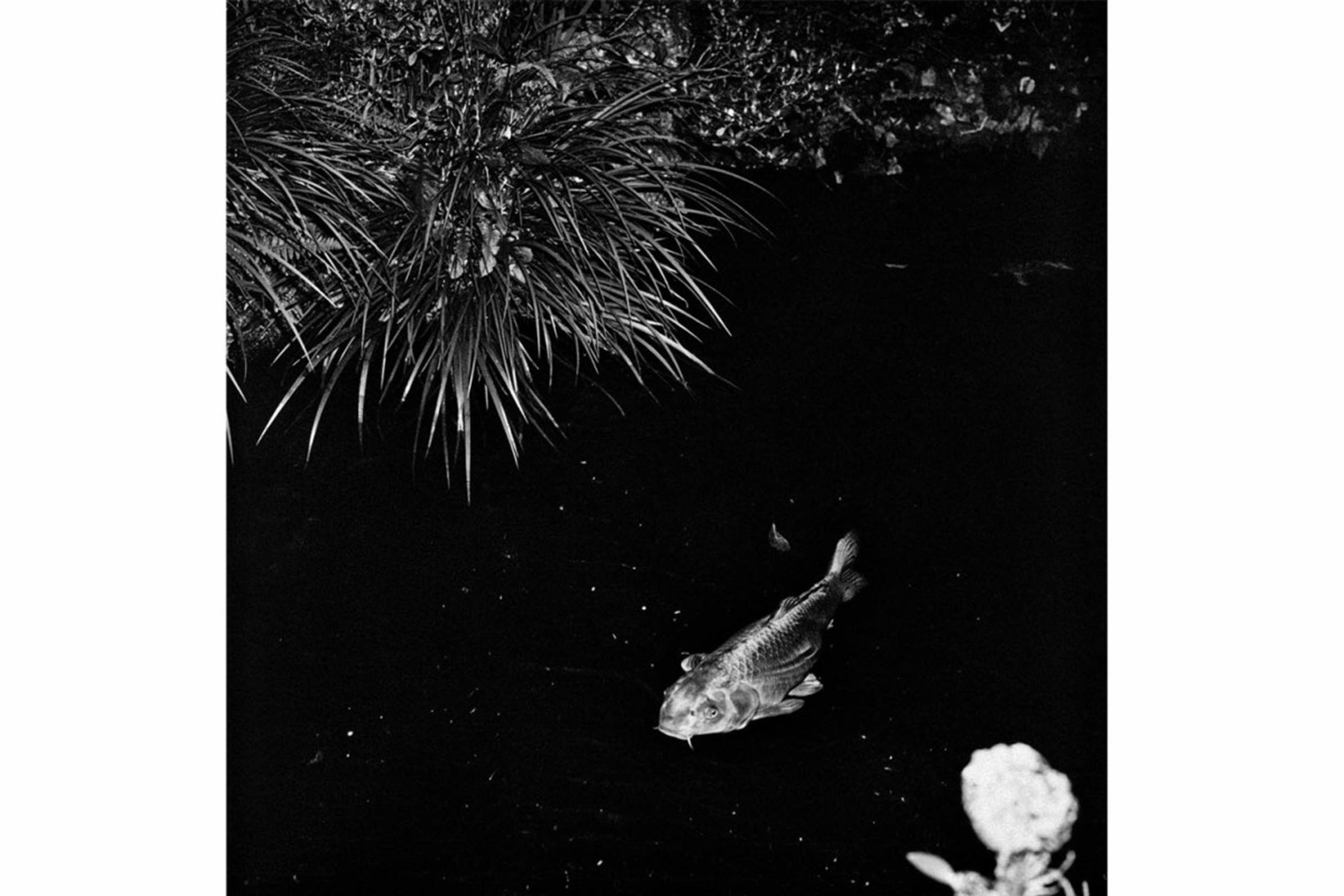

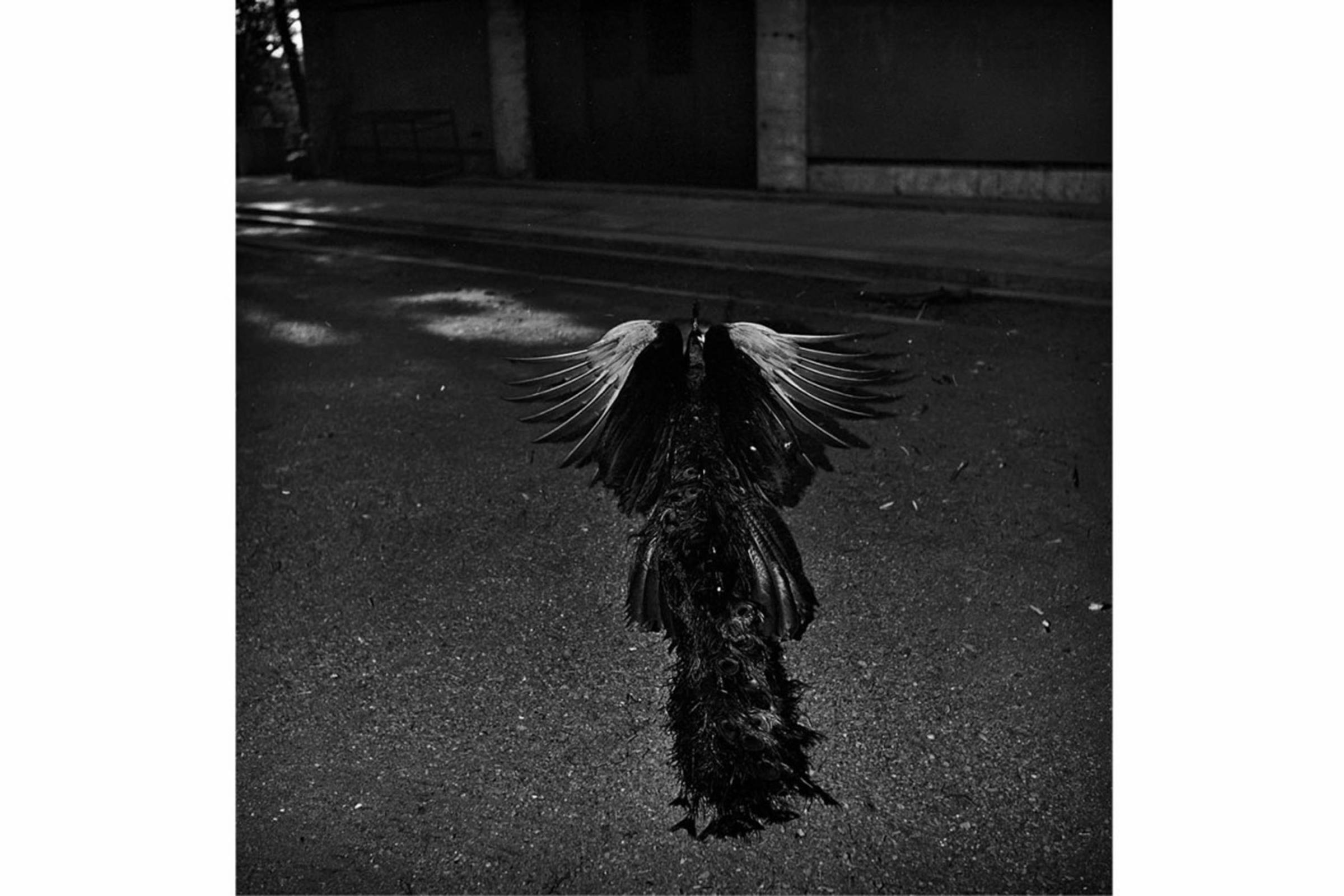

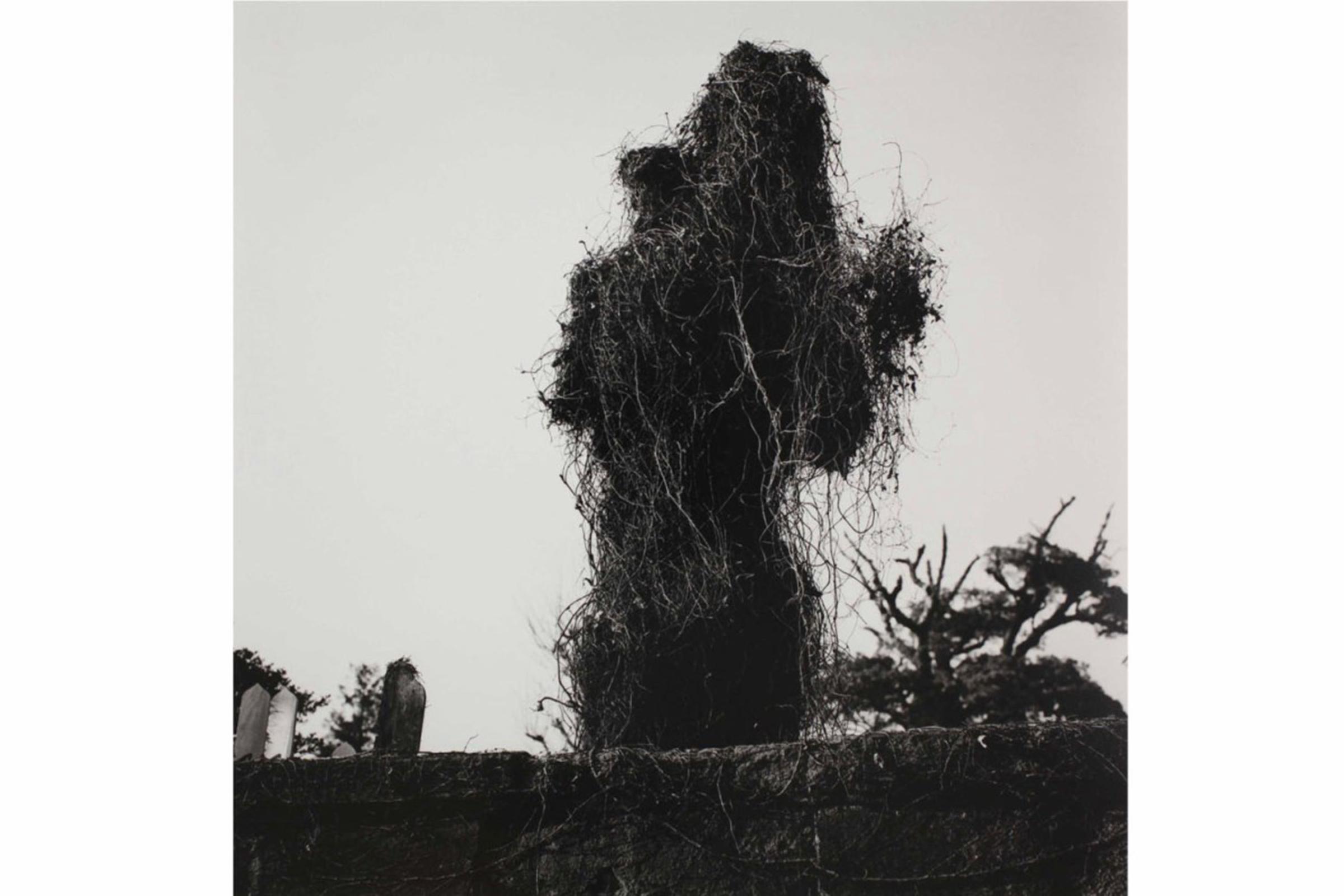

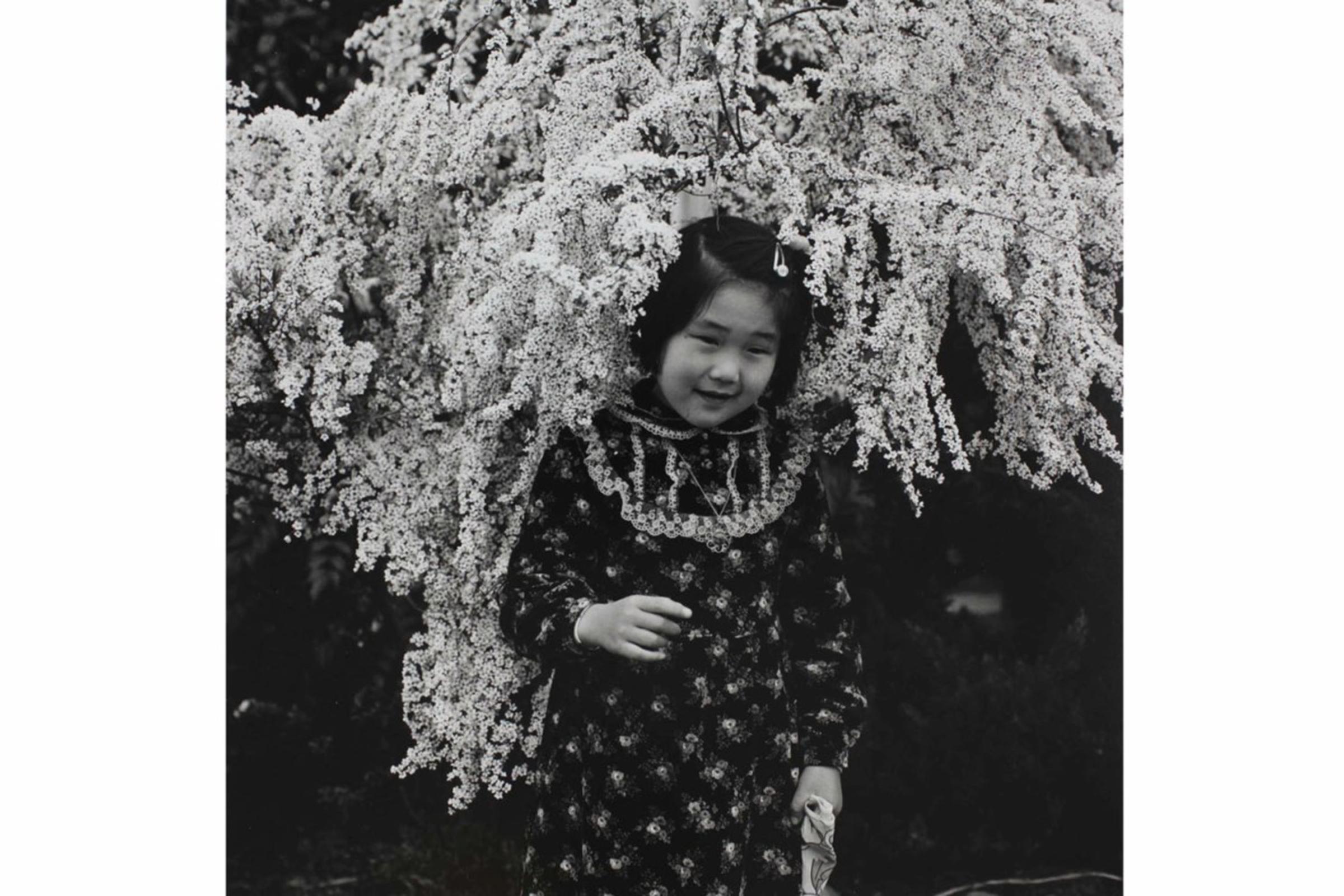

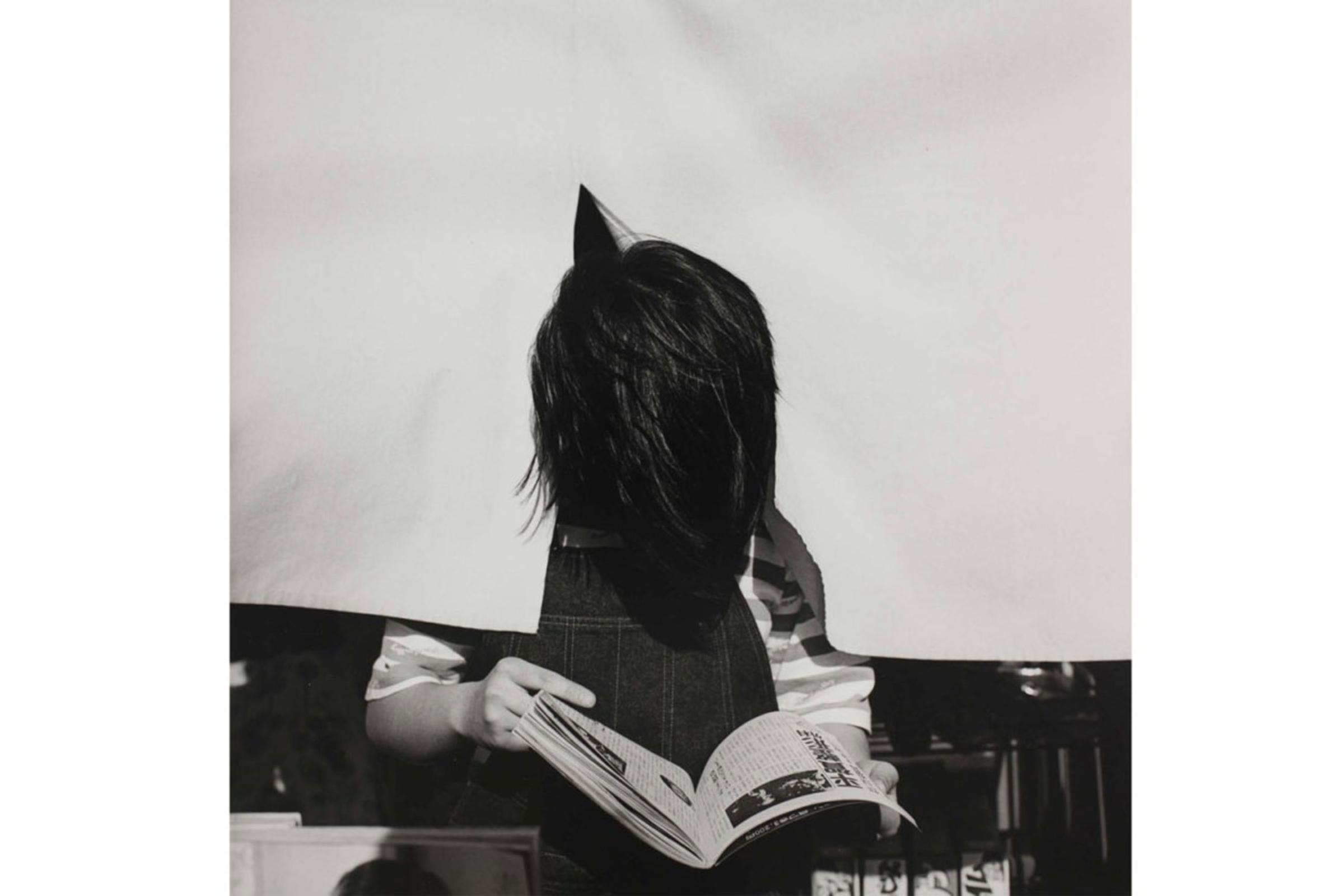

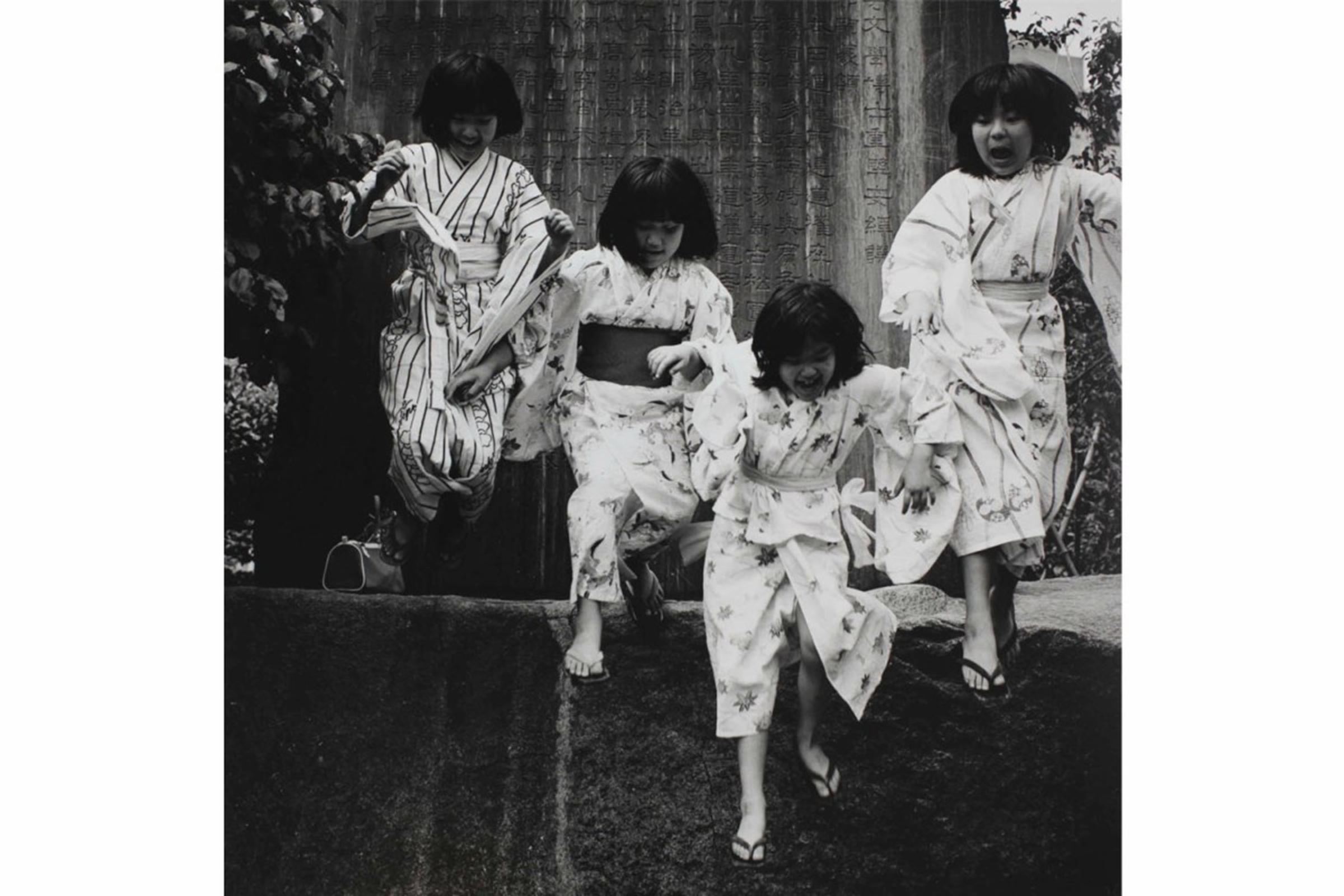

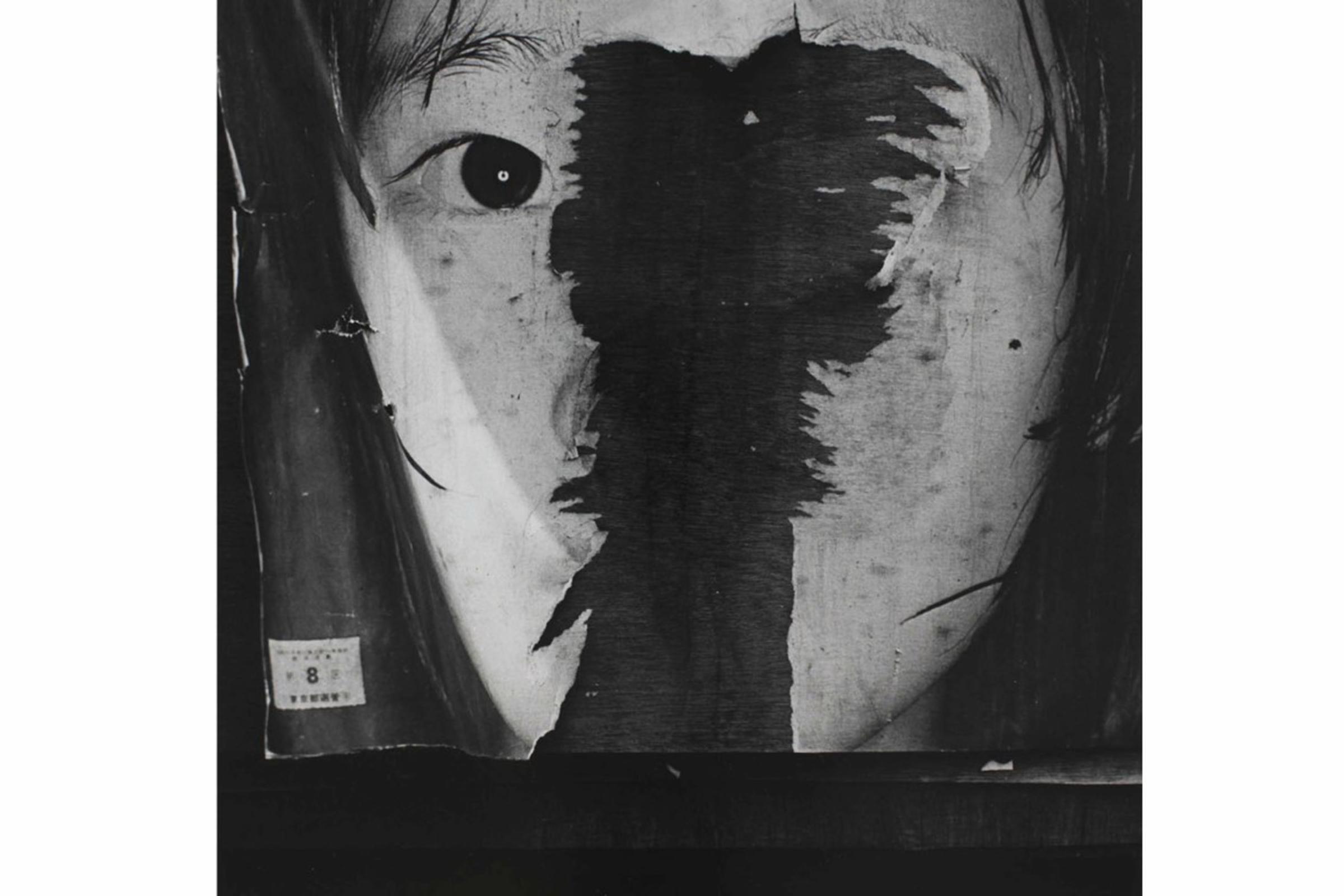

This 1972 image is typical of Suda’s approach to photography: careful observations of the quotidian, acute attention to framing and formal balance in the image, and an emphasis on subtle gestures. Suda’s black-and-white photographs in square format are deliberate in the sense that his subjects often fulfill a symbolic purpose within the frame. His images can be fleetingly looked at and enjoyed for their aesthetic value, but they can also be studied and analyzed like a sociological project on the complexities of human behavior.

Born in 1940 in Tokyo, Suda’s substantial body of work, which ranges from the 1960s to the present day, provides a fascinating window into a period in Japanese history that witnessed radical social, economic and political change. Suda graduated from the Tokyo College of Photography in 1962, and he began his professional career between the years 1967 and 1970 when he worked as a stage photographer for an independent theatre troupe called Tenjo Sajiki led by the widely acclaimed artist and writer Shuji Terayama. At that time in the late 1960s Tenjo Sajiki was at the very heart of a radical underground movement thus proving Suda with access to numerous artists who have, in the meantime, become household names in the Japanese art scene.

An important shift occurred in 1971 when Suda started to work on self-guided photography projects. In the context of Japanese language, this shift can be best illustrated with the subtle but important difference between the English loanword kameraman and the Japanese term shashinka: the former being a professional photographer such as a studio or a newspaper photographer, whereas the latter signifies an individual who pursues photography as an art form. Suda’s progressive development as a photographer also corresponds to an era in which the opportunities of the medium photography were radically reevaluated by the Japanese avant-garde.

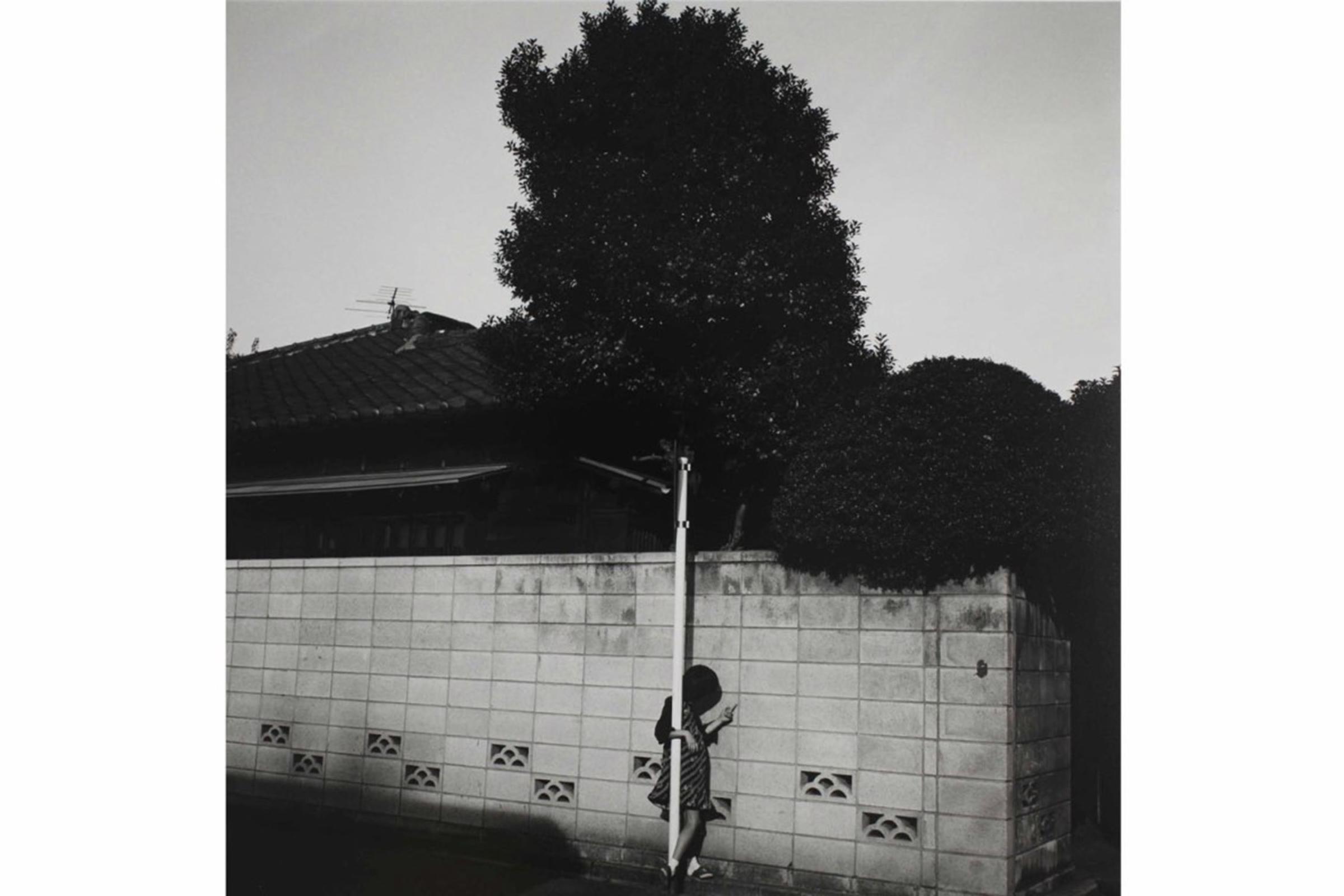

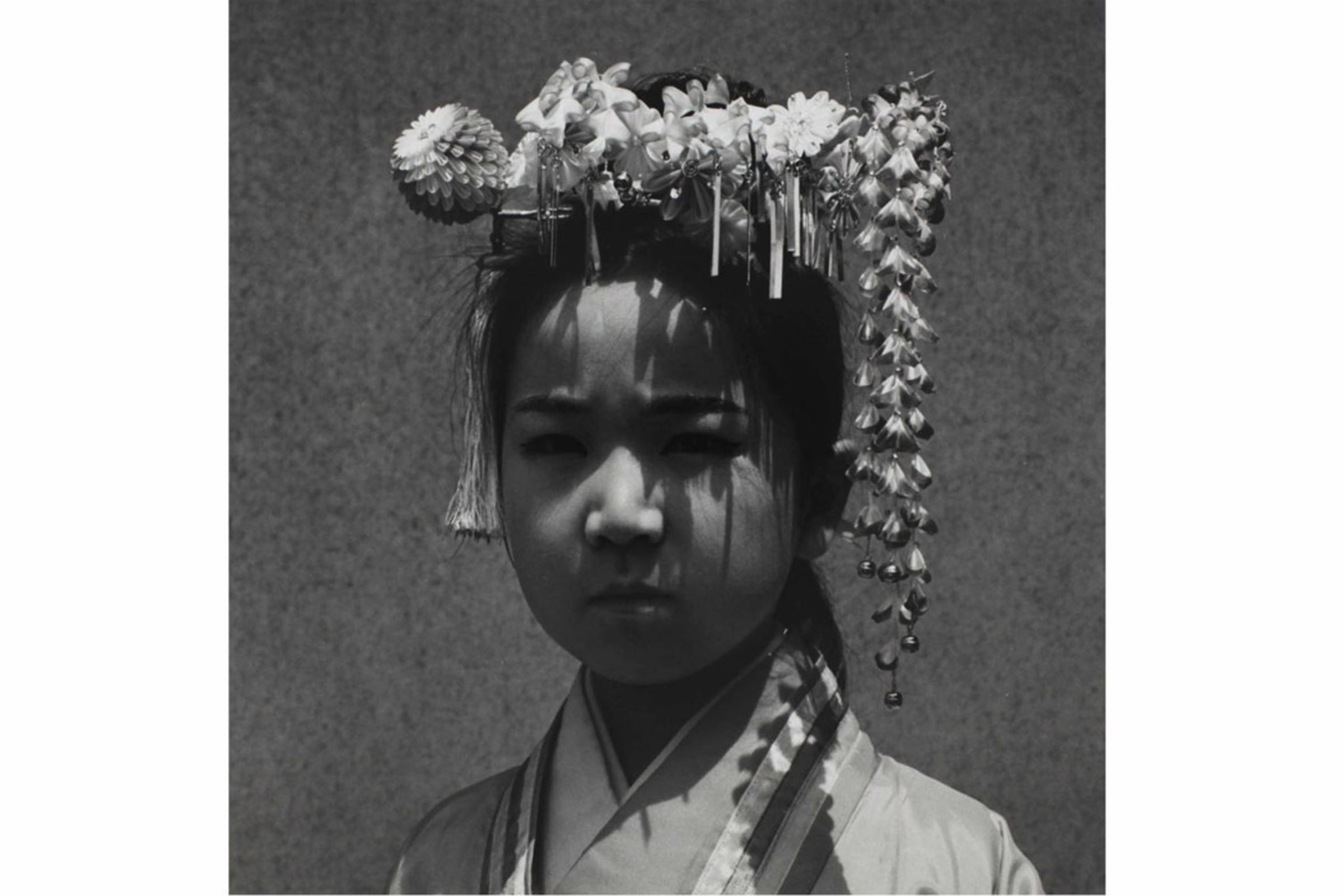

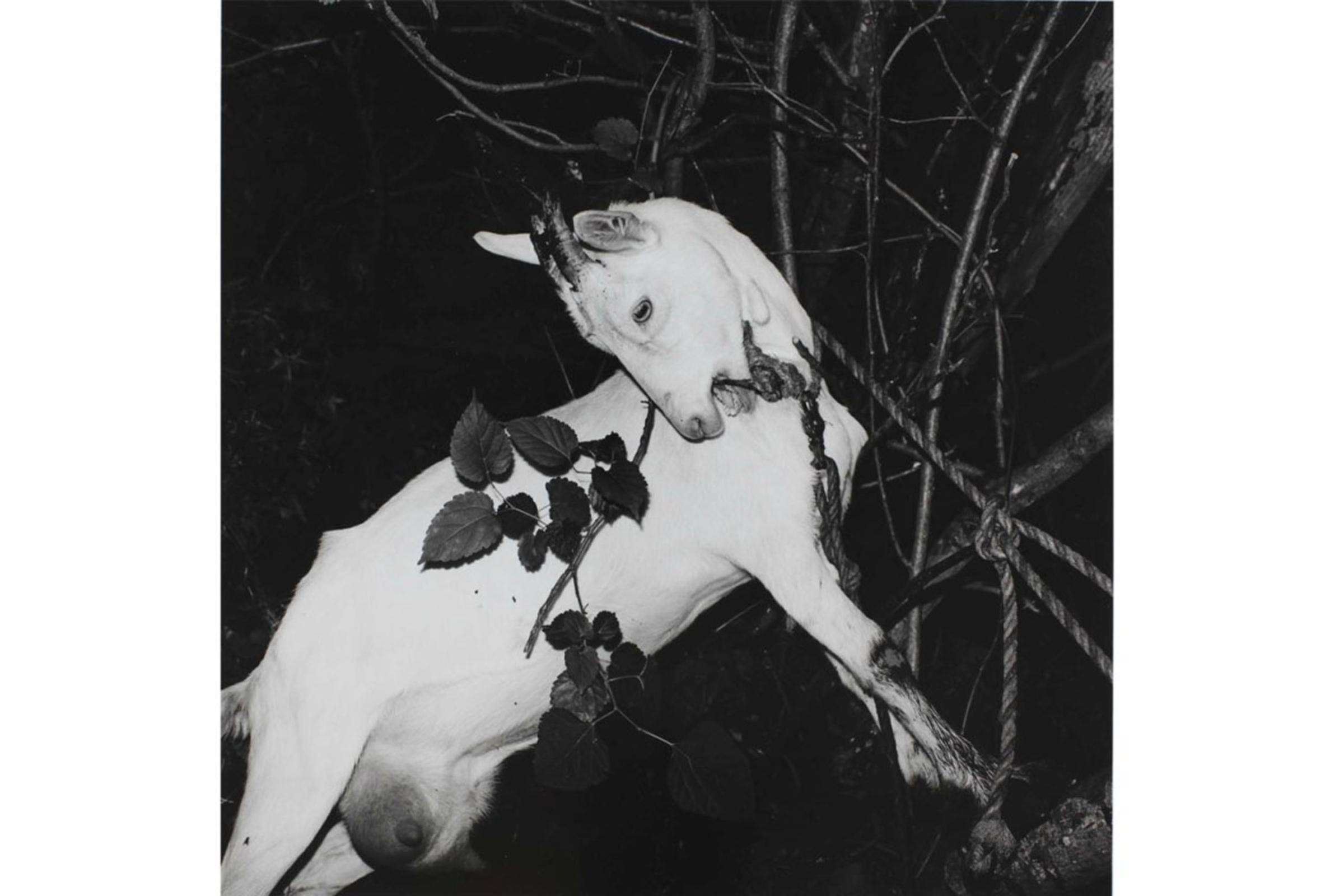

Suda’s most acclaimed project, Fushi Kaden which was first serialized in the magazine Camera Mainichi and then published as a book in 1978, is a photographic homage to Noh — a major form of classical Japanese musical drama: the title of the project references a fifteenth-century book written by a prominent director and actor in the genre. Suda’s contemporary interpretation of traditional Japanese theater is produced by a variety of images that depict performers or musicians at local festivals. Theatricality is also referenced more subtly, with several street scenes in which Suda is capturing a form of theater of the banal unfolding in front of his camera.

The pattern established by Suda’s acclaimed work can be observed in photographic projects produced in subsequent years – the majority of which are based in Tokyo. Even though he seeks to make the ordinary look extraordinary — with his work often appearing utterly surreal — Suda’s photographs promote a heightened awareness of the everyday. Clearly influenced by his formative years working as a stage photographer, for Suda the streets have become the stage, strangers have become actors, objects have become props, and the camera a tool to put order into this world.

Issei Suda: Life In Flower, 1971-1977, showing at the Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery, closes Oct. 18.

Marco Bohr is a photographer and writer based in the United Kingdom. He runs the Visual Culture Blog and can be found on Twitter @MarcoBohr.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com