The U.S. military’s nuclear force — both its hardware (the weapons) and its software (the people who operate those weapons) — is in disarray. That can only come as a surprise to those who don’t concede the Cold War is over, and that neither the funding, nor the required mindset, exists to keep it going indefinitely.

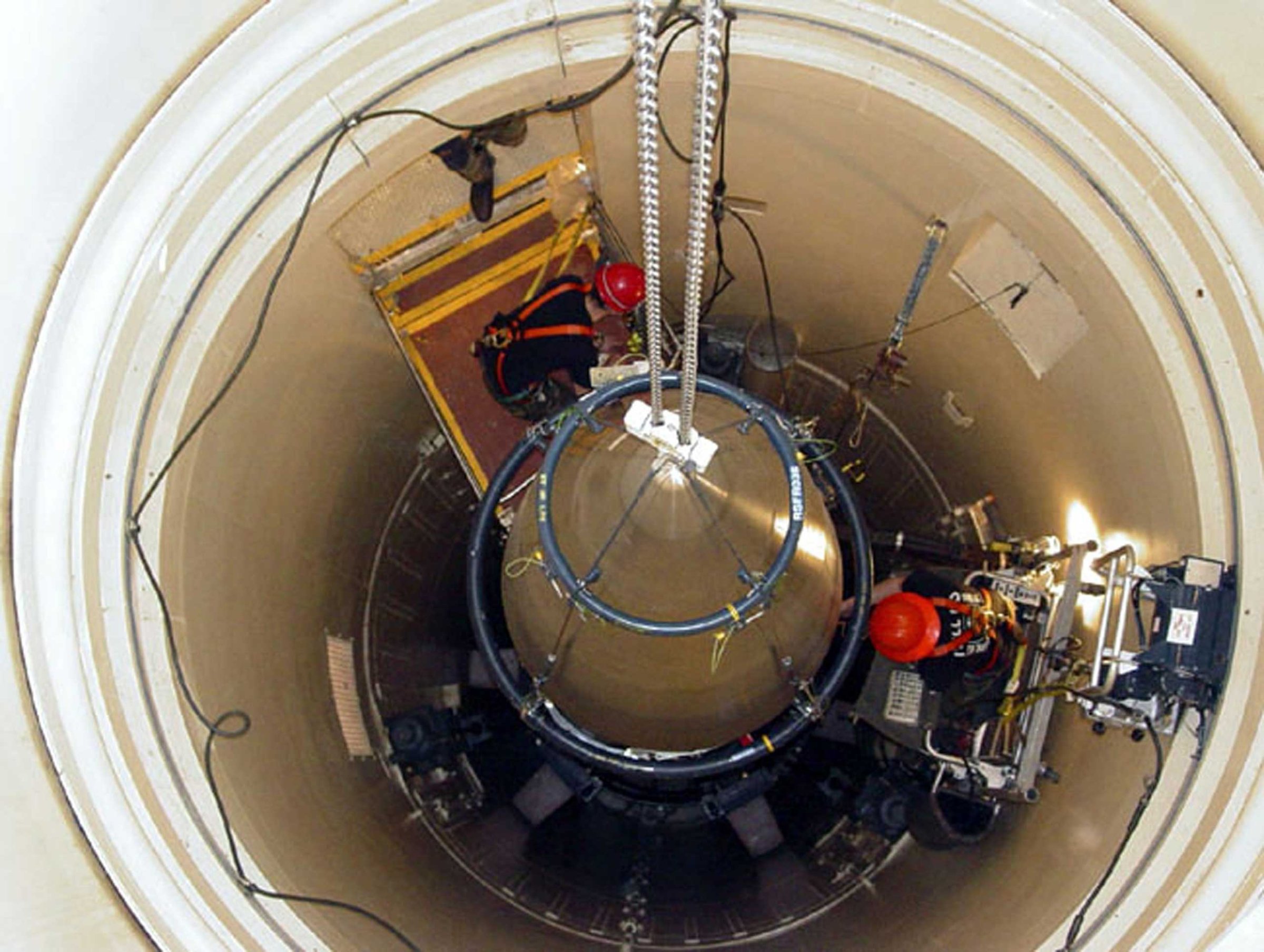

Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said Friday that a pair of reviews calls for spending about $7.5 billion over the next five years to shore up the nation’s nuclear weapons, as well as the bombers, land-based missiles and submarines that carry them. “The reviews found evidence of systematic problems that if not addressed could undermine the safety, security and effectiveness of the elements of the force in the future,” he said. “These problems include manning; infrastructure; and skill deficiencies; a culture of micro-management; and over-inspection and inadequate communication, follow-up, and accountability by senior department in nuclear enterprise leadership.”

There was a palpable sense of national mission when you visited nuclear sites during the Cold War. While that remains true at most sites, there’s a feeling gleaned from speaking with current nuclear officers that their mission isn’t as vital as it once was. Congress feels the same way, which is why the nation’s nuclear-weapons organization has been nickled-and-dimed, relatively speaking, for the past 25 years (although it’s slated to cost $1 trillion over the next 30 years).

Hagel ordered the reviews in January, after reports of widespread cheating surfaced among the airmen operating the Air Force’s intercontinental ballistic missiles at Montana’s Malmstrom Air Force Base. The Navy also discovered that some of its sailors had apparently cheated on tests involving the nuclear reactors that power some of the service’s ships and subs. The panels recommended more than 100 changes, which will be monitored by a newly created Nuclear Deterrent Enterprise Review Group that will report directly to Hagel every three months.

“Our nuclear triad deters nuclear attack on the United States and our allies and our partners,” Hagel told reporters. “It prevents potential adversaries from trying to escalate their way out of failed conventional aggression, and it provides the means for effective response should deterrence fail.”

Arms-control advocates disagree. “Apart from deterring a nuclear attack, nuclear weapons play an increasingly limited role in U.S. national security policy, but our arsenal is still configured and sized for a Cold War world that no longer exists,” says Kingston Reif of the non-profit Arms Control Association. “There are simply no plausible military missions for these weapons given their destructive power, the current security environment and the prowess of U.S. conventional forces.”

The Air Force has already made improvements. Last month, missile launch officers became eligible to receive up to $300 monthly because of the importance of their mission. New uniform and cold-weather gear also have been provided the ICBM crews, who work in North Dakota and Wyoming as well as Montana. It has added 1,100 more troops to its nuclear force (the Navy’s hiring 2,500 more). Last week, the Air Force awarded 25 airmen the new Nuclear Deterrence Operations Service medals to honor their work.

The roots of the problem runs deep. Over the past two decades, the Air Force has shifted responsibility for its ICBMs around like an unwanted child. The missiles bounced from Curtis Lemay’s Strategic Air Command, where they had been since becoming operational in 1959, to Air Combat Command in 1992. They moved to Space Command in 1993, and finally to Global Strike Command in 2009, created as a mini-SAC following a pair of nuclear snafus of 2007-08 that led to the cashiering of the Air Force’s top two officials. “We mattered under Strategic Air Command,” Dana Struckman, a retired colonel who manned missiles from 1989 to 1993, said earlier this year. “The Cold War was still on, and we had a sense of purpose that I don’t think they have today.”

Some official Air Force reports acknowledge the problem. “Many current senior Air Force leaders interviewed were cynical about the nuclear mission, its future, and its true (versus publicly stated) priority to the Air Force,” a 2012 Air Force paper said. Commanders routinely told nuclear airmen that they were in a “sunset business” and “were not contributing to the fight that mattered,” it added. A second Pentagon study noted that most airmen manning ICBMs “were not volunteers for missile duty.”

Hagel conceded the problems aren’t new. “Previous reviews of our nuclear enterprise lacked clear follow-up mechanisms,” he said. “Recommendations were implemented without the necessary follow-through to assess that they were implemented effectively. There was a lack of accountability.” To fix that, he said he has assigned Pentagon cost experts to monitor the new changes being made so that the Defense Department knows “what’s working and what’s not.”

The defense secretary pledged to “hold our leaders accountable up and down the chain of command.” That’s because the problems aren’t confined to the lower ranks. The Air Force fired Maj. Gen. Michael Carey — in charge of all the nation’s ICBMs — last year after an official trip to Moscow, where he drank excessively and cavorted with “suspect” women. During a layover at a Swiss airport, witnesses told Pentagon investigators that Carey “appeared drunk and, in the public area, talked loudly about the importance of his position as commander of the only operational nuclear force in the world and that he saves the world from war every day.”

Those still in charge don’t see their assignment as a Cold War mission. “I don’t think we’re any more a Cold War force than an aircraft carrier, or Special Ops, or the UH-1 helicopter,” Lieut. Gen. James Kowalksi, chief of Global Strike Command, said of his nuclear arsenal last year. A Russian first strike, in fact, has become such a “remote” possibility that it’s “hardly worth discussing,” he said. “The greatest risk to my force is an accident. The greatest risk to my force is doing something stupid.”

Kowalski became the No. 2 officer in U.S. Strategic Command in October 2013, overseeing the nation’s entire nuclear arsenal, after President Obama fired Vice Adm. Tim Giardina from the post for allegedly gambling in an Iowa casino with counterfeit chips. The charge — a felony — happened at Horseshoe Council Bluffs Casino, a 15-minute drive across the Missouri River from the nation’s nuclear headquarters.

Hagel implied Friday that operating the nation’s most deadly weapons in the 21st century is kind of like using enough wax and elbow grease to shine up an old jalopy: “We must restore the prestige that attracted the brightest minds of the Cold War era, so our most talented young men and women see the nuclear pathway as promising in value.” Only one problem: the most talented young men and women know the Cold War ended before they were born. Given that, they also know there’s no way to restore the resolve and purpose those manning the weapons against the Soviet Union once felt.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com