This story originally appeared on xoJane.com.

I know, I know: you’re already tired of the Lena Dunham conversation.

I can’t blame you. It has been a seemingly endless conga line of vitriolic, ill-conceived thinkpieces that do little to advance the discussion. The National Review’s Kevin Williamson wants you to shame and pity her. Salon’s Mary Elizabeth Williams wants people to stop calling Dunham an abuser and taking her out of context. Katie McDonough hates that Dunham detractors are ignoring her sister’s perspective. Dunham herself considers the scandal a right-wing smear campaign and is threatening to sue Truth Revolt, the conservative outlet that broke the story. The conversations currently happening on social media aren’t much different; a number of high-profile feminists and celebrities are taking to Twitter to defend Dunham, dismissing the encounter as childhood curiosity.

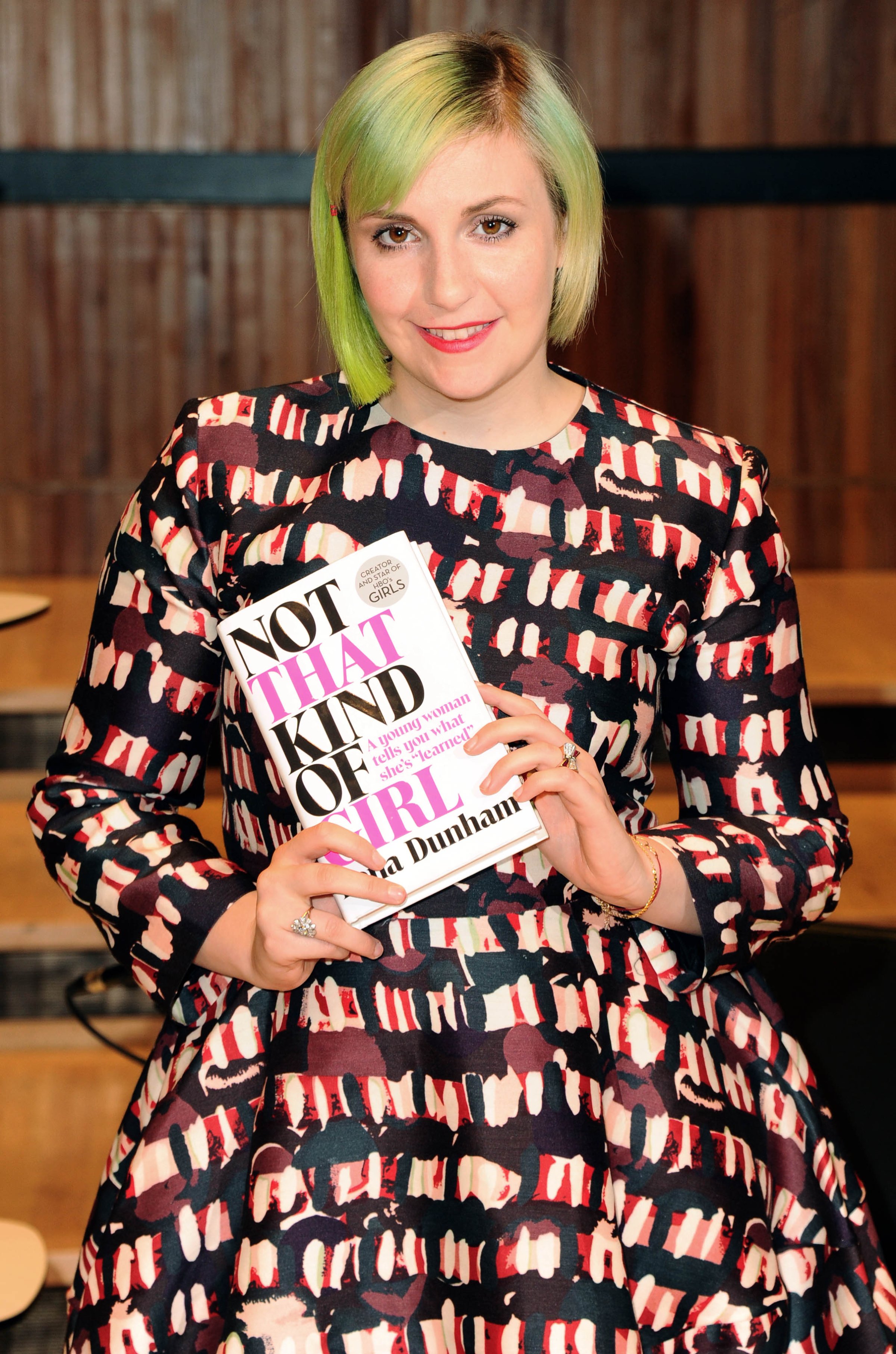

By now, you’ve already seen the disturbing excerpt from Dunham’s New York Times’ bestseller, “Not That Kind Of Girl.” If you haven’t, the passage is one quick Google search away. In it, she describes how she would bribe her baby sister with affection. It comes off as predatory and abusive, and naturally, people were alarmed. It is handled with all the finesse of a bad sketch comedy writer. It’s the type of thing that no decent editor should ever, ever greenlight.

On one hand, I can understand the vigorous defense: Lena Dunham is, quite possibly, the most accessible and relatable feminist celebrity in recent history. She’s a Girl-Powered Everywoman who abashedly lays herself bare, literally and figuratively, for the world to see. She isn’t model-thin or classically beautiful. And she is rarely, if ever, apologetic about how she lives her life. Ideally, she is the Fourth Wave Prototype.

But no hero is without imperfection, and when said hero messes up on a nuclear level, it’s okay to not only acknowledge it, but to hold the hero accountable for their actions. We don’t have a problem with doing it when it’s Woody Allen, or Roman Polanski, or Chris Brown; it’s always easier to call out the folks we don’t like. But mainstream feminism’s outright refusal to even approach this objectively alienates those of us who identify as abuse survivors, and it reinforces the idea that certain people can get away with bad behavior if the others really, really, really like them a lot.

While I’m not sure if I’m comfortable with the idea that this unfortunate lapse in judgment should be a teachable moment, it does illustrate a need for a broader discussion about children and sexually harmful behavior.

According to Stop It Now!, a non-profit that focuses on child abuse prevention, over a third of all sexual abuse is committed by someone under the age of 18. (My abuser, a family friend, was 17.) A child using tricks and manipulation to gain sexual favors from another may not even realize that she’s engaging in harmful behavior, and it doesn’t necessarily mean that the child will have a predilection for sexual violence. Still, Stop It Now! suggests that professional help is the best route for any child struggling with impulse issues.

It wasn’t until the week before I left for college that I told my mother what had happened with that family friend, but there were definitely warning signs along the way. One particular incident involved a seven year-old me “acting out” with a couple of other kids in my afterschool program, and I hated getting undressed for anything. But I was too afraid to tell my mother because didn’t want her to fall out with one of her dearest friends. Though she was an abuse survivor herself, she probably wouldn’t have known what to look for, or what to do besides ripping off the boy’s genitalia and throwing it in Lake Michigan.

Stop It Now! has a checklist for parents and caregivers to know the signs. Here are a few:

Also, trusting your gut could make all the difference, according to the site. Most parents expect their children to come to them when they’re being abused and that rarely happens, which contributes to denial, along with common misunderstandings about sexual abuse, says Stop It Now! Speaking up is the best form of prevention.

The Dunham debate will probably rage on for the weeks and months to come, and people will continue to rehash and regurgitate eveything that’s already been said. But the silver lining, as I see it, is that we will finally be able to talk about this in a more thoughtful, productive way. And, hopefully, spare some children a lot of pain.

Jamie Nesbitt Golden is a journalist originally from Chicago.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com