When Barack Obama received an Indian Prime Minister at the White House for the first time in 2009, the greatest excitement came not from any chemistry between him and Manmohan Singh, nor even from the unstinting (if dutiful) affirmation of values shared by their two great nations.

The buzz came, instead, from an audacious couple who hoodwinked the world’s tightest security cordon and gate-crashed the state banquet. Tareq and Michaele Salahi—remember them?—upstaged the official guests in the popular imagination. Somehow, it seemed entirely fitting that a Gatsbyesque businessman from Virginia and his gaudy blond wife should have saved us all from the ineffable dullness of Manmohan Singh.

Singh’s successor, by contrast, is not a dull man, nor one easily upstaged. When Narendra Modi visits the White House for the first time on Sept. 29, he will be a powerful magnet for attention. His is an awkward, even embarrassing, visit: the U.S. State Department had placed him on a visa blacklist in 2005, until his party waltzed to victory in India’s elections in May. The reason? Disquiet over his alleged role in the anti-Muslim riots that racked Gujarat in 2002, when he was chief minister of the western Indian state. And there was likely a belief in the State Department that it was safe to deny Modi entry since he would surely never amount to anything more than a regional politician.

Those riots and that visa denial are now history, for better or worse. Modi took India by storm, and in the months since he became Prime Minister, he has gone about reconstructing India’s foreign policy. Some would say he is revolutionizing it.

India was, until recently, a country with a rudderless foreign policy, rooted more in airy-fairy internationalism than in hardheaded national interest. A continuing fidelity to nonalignment—which, in effect, is simply nonalignment with the West—lived on in the country’s Foreign Ministry. For a while, when President George W. Bush was in the White House, India teetered on the edge of an alliance with Washington.

Certainly, Bush did everything he could to win India over to his side, concluding a nuclear deal with New Delhi that would have been unthinkable under any previous President. But the alliance has failed to mature under Obama, who, to be fair, has had little time for India, given the many crises that have bedeviled his Administration.

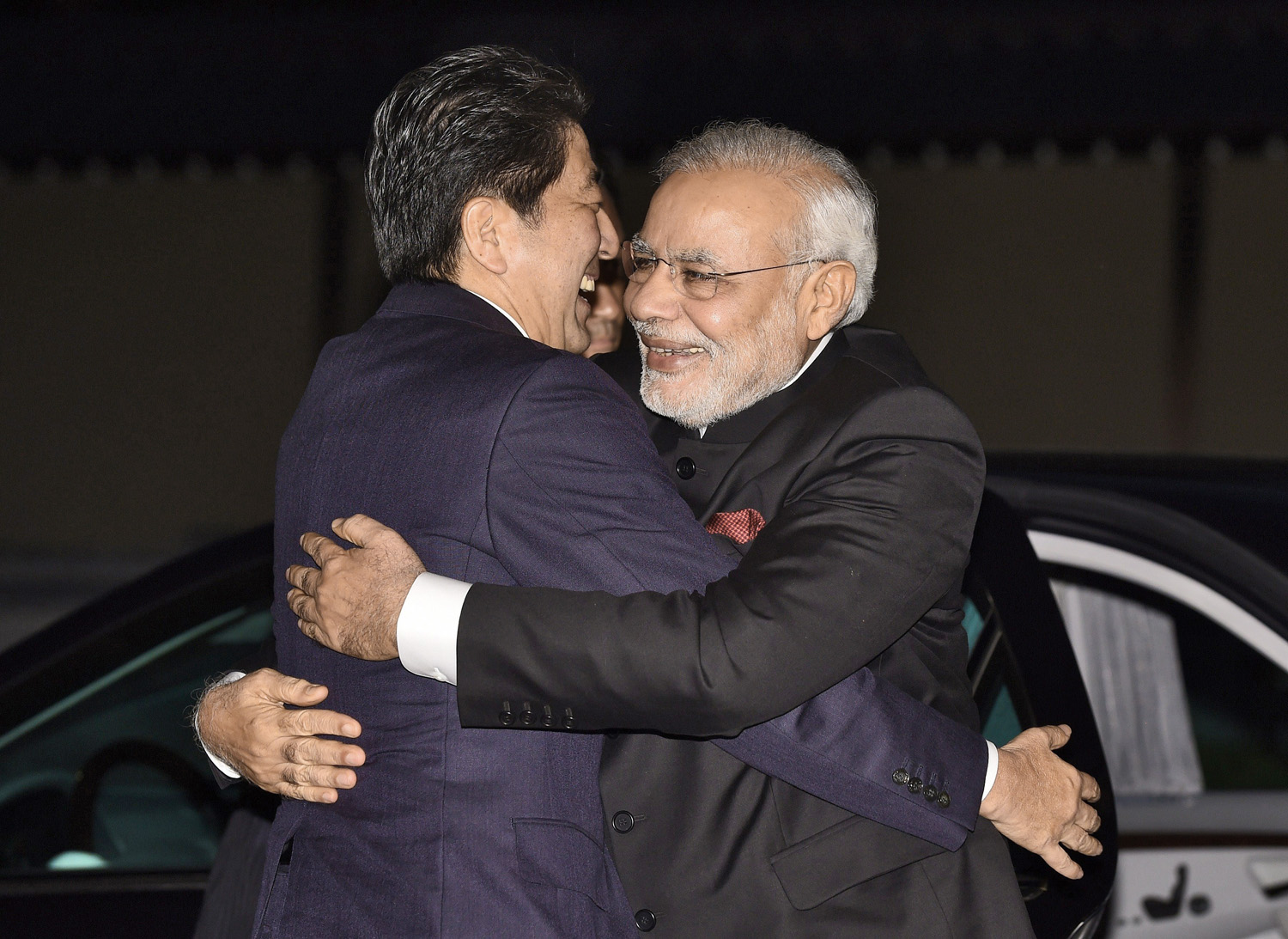

Under Modi, though, India is charting a policy of robust national self-interest, with Japan emerging as its central foreign partner. The new Prime Minister traveled to Tokyo in late August and pulled off one of the most successful state visits in Indian history. And on Sept. 17, Chinese President Xi Jinping came calling, vying for the favorable attention that Modi had just bestowed on Japanese Premier Shinzo Abe.

Japan and China are courting India with gusto. Tokyo, which feels cut adrift by an underconfident Washington, wants a partnership with India to keep China at bay. Beijing, disconcerted by a galloping Indo-Japanese alliance, wants to prise New Delhi away from Tokyo. India continues to be deeply suspicious of an expansionist China, even as it covets its investment. Just one day after Xi set foot in India, 1,000 Chinese soldiers made a distinctly undiplomatic incursion into Indian territory.

In India, meanwhile, illusions about a meaningful alliance with the U.S. have melted away. This is healthy for Indo-U.S. ties, which are better embedded in pragmatism than wishful thinking. It takes diplomatic pressure off the U.S., for whom forging a formal relationship with India is always going to be tricky. An India strengthened on its own terms is likely to be a better partner for the U.S. than a thin-skinned India that plays perpetual second fiddle, always sensitive to slights and disappointment.

The Modi who will visit Obama on Sept. 29 comes not as a supplicant. Obama’s focus is now firmly on the terrorists of the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) and the Middle East, not on the subcontinent. In any case, Modi’s primary interlocutors in the U.S. are not in the White House. They are in the American private sector. All he needs is a firm handshake from Obama. Oh, and that fulsome affirmation of shared democratic values.

Varadarajan is the Virginia Hobbs Carpenter Fellow in Journalism at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com