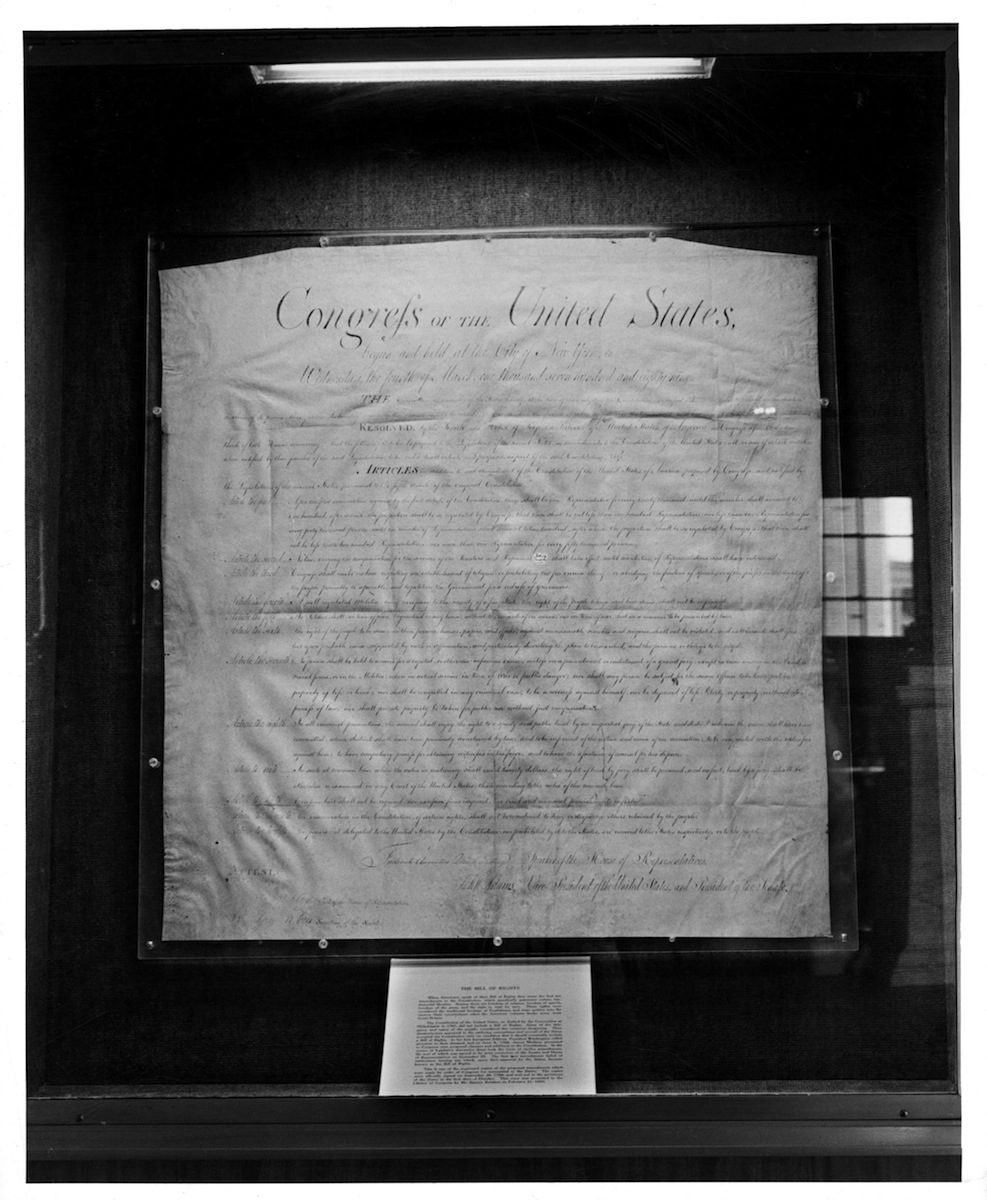

On Sept. 25, 1789, Congress approved the Bill of Rights, and 13 copies were dispatched to the 13 American states for ratification. The past 225 years have been pretty tame for most of the original copies, but one of the yellowed parchment sheets — the version destined for North Carolina — ended up on a much longer journey than its drafters could have imagined, involving shady collectors, an FBI sting operation and a theft masked by the fog of war.

Things started out so calmly: the North Carolina document spent a relatively placid 75 years in the state archives in Raleigh after the state quickly ratified the amendment. A state clerk placed it among archival papers in the Capitol building, and it stayed in Raleigh until near the end of the Civil War.

Then, in 1865, North Carolina’s copy of the Bill of Rights began a long and unexpected circumambulation of the country. A Union infantryman serving under U.S. General William Tecumseh Sherman’s “marauders” during the occupation of Raleigh broke into the state archives and stole the document, among other papers, as a souvenir, bringing it home to Tippecanoe, Ohio. The unnamed Union soldier pawned it a year later to a Mr. Charles Shotwell, a grain salesman in Troy, Ohio, for a cool $5.00 (about $75 today).

(It seems neither party considered it a priceless cultural artifact. There weren’t many Supreme Court cases in the 19th century that addressed the first ten amendments, and in many respects the document didn’t have quite the same judicial value that it has today.)

The North Carolina document, a little worse for the wear, resurfaced briefly when Shotwell tried to sell it, but disappeared again in the 1920s. Meanwhile, perhaps unbeknownst to the holder of the disappeared North Carolina document, the importance of the Bill of Rights was evolving. As the Supreme Court considered a number of high-profile cases that focused on issues in the Bill of Rights, those amendments rapidly acquired a more elevated status in American cultural heritage. Texas v. Johnson (1989) established flag burning as a form of symbolic speech protected by the First Amendment; Miranda v. Arizona (1966) held that police must inform people of their Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate themselves, or their confessions can’t be used as evidence at trial; Engel v. Vitale (1962) found state-composed prayer requirements unconstitutional by the First Amendment.

By the mid-1940s, the Bill of Rights had became cultural touchstone. In 1944, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for a “Second Bill of Rights” that would protect the rights of American workers, and included a laborer’s “right to a useful and remunerative job,” and a businessman’s right to be free of “unfair competition and domination by monopolies.” And the G.I. bill of 1944, which famously gave World War II veterans access to low-cost mortgages and cash payments for educational expenses was nicknamed “the G.I. Bill of Rights.” Throughout the 20th century, TIME had cause to cover a proposed Teachers’ Bill of Rights in 1946, a 1988 proposed Taxpayers’ Bill of Rights, and President Clinton’s Patients’ Bill of Rights in 1998.

North Carolina’s copy could no longer be considered a scrap to pawn off for $5.00 to a cheap Ohio grain salesman. Archivists in the state dreamed of bringing it home. “It developed a kind of mythology around it,” says David Howard, author of Lost Rights: The Misadventures of a Stolen American Relic, a book on the North Carolina documents’ misadventures. “It became a very personal quest to have this thing back.”

Wayne Pratt, an antique collector and salty New Englander with a thick Boston accent was the next to acquire the North Carolina Bill of Rights. A regular on PBS’ “Antiques Roadshow,” Pratt told potential buyers he found the document in upstate New York antiques store and deceptively claimed it couldn’t be traced back to any state.

His downfall came when he tried to sell the document to the National Constitution Center, a new museum in Philadelphia. The National Constitution Center sent it to Washington historians, says Howard, who found a faint bit of handwriting on the back side of the document. It turned out the handwriting belonged to the very same North Carolina state clerk who, in the autumn of 1789, had first signed it for record-keeping purposes before shelving it in the archives. When North Carolina officials found out their missing Bill of Rights had resurfaced, the state’s Governor, Mike Easley, and the Raleigh U.S. Attorney’s office were ready to play hardball. The attorney’s office brought the Federal Bureau of Investigations on board. An undercover agent posing as a philanthropist met Pratt’s lawyer in a high-rise Philadelphia office building, bearing a $4 million check to purchase the Bill of Rights. (Think American Hustle, without the bad hair.) Pratt’s lawyer examined the check, then called his appointed deliveryman, who was waiting in a coffee shop down the street with the North Carolina Bill of Rights in a large box.

“The deliveryman brings it into the conference room,” says Howard, “and they all had a chance to bask in it.”

Then the signal was given, and half a dozen FBI agents burst into the room. The gig was up. The Bill of Rights was seized and Pratt’s hapless lawyer was interrogated. After some legal wrangling, the Bill was returned to North Carolina, where in 2007 it took a ceremonial tour of its home state and then at last returned to Raleigh.

In 1990, TIME had lamented the loss of five of the original 13 states’ Bill of Rights, including Georgia’s, New York’s, Maryland’s, Pennsylvania’s and North Carolina’s. “North Carolina thinks a Yankee yegg grabbed its historic document during the Civil War when General William Tecumseh Sherman tramped through Raleigh,” the article read. “What ever happened to the precious parchments?” Today, at least, we know about one of them.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com