Looking for a review that doesn’t spoil the ending? Or do you want to read every piece of analysis about the unexpected twists of a movie like Gone Girl after you’ve seen it? We’re debuting a new feature on Time.com, developed by TIME’s tech lead Mark Parolisi, that lets you have it both ways. Click here to reveal the full analysis if you’ve already seen the film (the spoilers will be in bold), and click again if you change your mind (the spoilers will appear blurred).

Their courtship was a dream: the meeting of attractive opposites — two journalists for New York magazines — reviving the fond banter of film stars past. On their first date, Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck), a small-town Midwesterner at ease in the big city, took rich, elegant Manhattanite Amy Elliott (Rosamund Pike) on a pre-dawn stroll to a bakery and kissed her, as powdered sugar fluttered around them like the finest snowflakes. Later, at a press party for the Amazing Amy children’s books her parents had written about her, Nick pretended to interview her and, from his notebook, removed an engagement ring.

A man — a woman too, but for now, the man — puts a lot of effort into the courtship role. He plays, he may even briefly be, the charming, considerate fellow, attentive to his woman’s every need or whim, just like the hero of some classic romantic comedy that ends at the altar. But that’s just the Old Hollywood version; in real life, the wedding is the beginning of a different story. And if courtship is a movie, marriage is a job that can become a grinding routine, an Ever After without the Happily. In the morning-after cinders of the honeymoon glow, a man may ignore his bride and find a younger woman with whom he can play another exciting game: adultery.

Did you ever wonder, even for an instant, if you could kill your spouse? Or be killed by the one you wed? And, if not, could others imagine it of you? Those are some of the taunts running through Gone Girl, the Gillian Flynn novel and the taut, faithful movie that she, as screenwriter, and David Fincher have made from it. In a property with all the killer-thriller tricks — sudden disappearance and violent death, dark motives and cunning misdirection — the true creepiness of Gone Girl is in its portrait of a marriage gone sour, curdled from its emotional and erotic liberation of courtship into a life sentence together, till death do they part. In Gone Girl, marriage is a prison, and each spouse is both jailer and inmate — perhaps even executioner, too.

Soon after the wedding, Nick and Amy lost their jobs. When he learned from his twin sister Margo (Carrie Coon) that their mother was dying of cancer, Nick abruptly decided to move back to North Carthage, Mo., and take Amy with him. They sold their brownstone — Amy’s brownstone — at a loss. Nick and Margo bought a bar, with Amy’s money, and he taught a journalism class at the community college. (In the book the course is called “How to Launch a Career in Magazines” — a little joke from Flynn, who became a full-time novelist when she was cashiered after a decade at Entertainment Weekly.) When not tending bar with Margo, Nick has kindled an affair with sexy student Andie (Emily Ratajkowski), which leaves Amy alone at home, with no job, doing… hey, what is this brilliant, industrious woman doing? Nick has no idea.

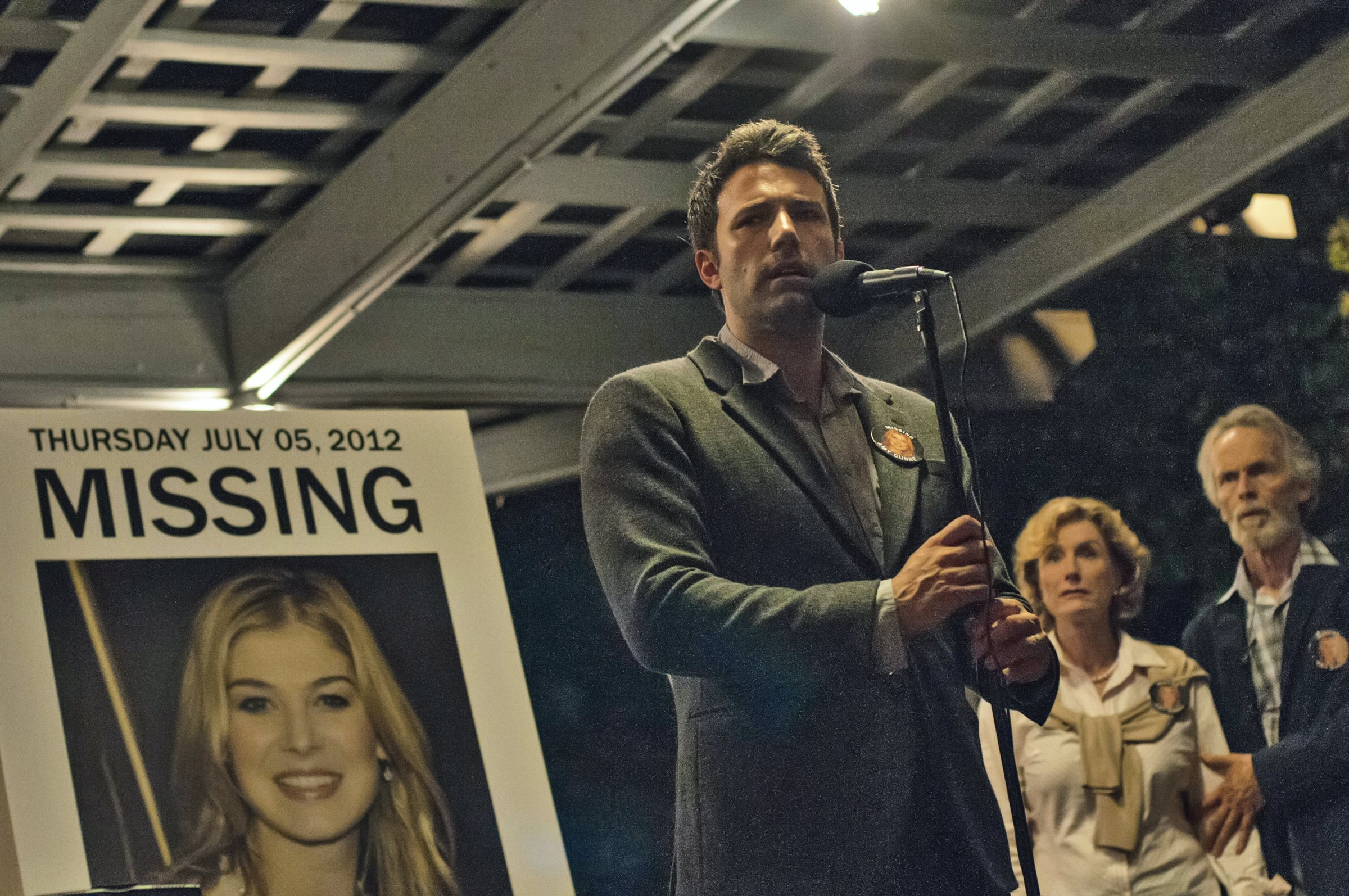

One thing that consumed her interest was preparing a treasure hunt for their fifth wedding anniversary, as she has done each year before: offering clues in rhyme to the hiding places of various gifts. But around noon on the big day, Nick discovers that Amy is gone from their home. Signs of a struggle, and blood wiped from the kitchen floor, suggest she was abducted, possibly murdered. She and Nick were heard arguing the night before, and when word of his affair gets around, he becomes the prime suspect — if not to Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens), the tough but sympathetic senior detective on the case, then to the neighbors and the avid, rabid media. Amy has left a diary, the record of a devoted wife’s growing suspicions and gnawing fear of her swine of a spouse, as well as the first clue in a brand-new treasure hunt. Nick now must juggle three uncomfortable roles: villain, victim and sleuth.

On the page, Gone Girl was a literary game: a tennis match of alternating chapters from Nick and Amy, with the reader offering to take each character’s side every few pages. Flynn simply — or, rather, complexly — interwove the narratives: Nick’s in the present, revealing more of his sins as he tracks the treasure-hunt clues, and Amy’s in the past, through her diary. He-said–she-said is fine for books, but movies play with the cinematic precept that seeing is believing: we show, you swallow. Given the dueling narratives, of which one, both or neither may be exactly true, it’s pretty impressive that Flynn and Fincher have managed to transfer this bookish jest successfully to the screen. The film amasses evidence against Nick through his own misdeeds, which we see, and through the testimony of Amy’s diary — a silk scarf that may become a noose — which we are shown. Like the novel, the movie detonates its big twist halfway through. So film reviewers must juggle the same ethical dilemma that faced book critics: whether or not to reveal the story’s shocking middle.

So here: Amy, exasperated with her lazy, careless husband and the glum life he had forced her into, faked her own murder and fashioned clues in the diary and the treasure hunt to frame him. She had carefully filched enough cash to live on while she moved in anonymity to the Ozarks. When she was robbed of her money, she contacted Desi Collings (Neil Patrick Harris), with whom she had a teenage affair and who remained desperately smitten, to set her up in his remote lakeside villa. Watching Nick’s declaration of love for her on tabloid TV, Amy decided he might after all be the man for her. Now she just had to figure out a way to explain her disappearance. That meant finding a new male villain.

“You’re not too smart, are you,” says sultry Kathleen Turner to full-of-himself William Hurt in the 1981 Body Heat. “I like that in a man.” In that Lawrence Kasdan thriller, the Turner character — who plays games and goes missing — has a temperature that runs “a couple of degrees high, around a hundred.” Amy is just the opposite: a cucumber-cool conniver, whose treasure hunt is, among other things, a test for Nick, to see if he’s as smart as he thinks he is. If so, he might be a worthy companion after all, suitable for siring a child — another Amazing Amy? Amy’s life was always partly fiction, from the time her parents wrote books about a fantasy image of their daughter: She became an expert at live-action role-playing, as a child, as Desi’s lover, then as Nick’s one-and-only. If she twists her own original plot, and returns to Nick, he’s bound to be as attentive as in their courtship. If not from gratitude, then from fear she can find a way to do him in.

Fincher tried a faithful version of a best-seller last time out, with his Americanization of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. That was a stillborn exercise compared with Gone Girl, which brings Nick and Amy to attractive, plausible life, and surrounds them with exemplary character actors. Kudos to Dickens, to David Clennon and Lisa Banes as Amy’s parents. (Also noteworthy are Scoot McNairy and Lola Kirke as friends you might not want to meet on the road. Only Harris disappoints; he lacks the hovering menace and ultimate bafflement of a stalker-lover.)

In Se7en and Fight Club, Fincher proved his suave mastery of film violence; in Zodiac, his way of clarifying the many clues in a murder thriller. As he showed in The Social Network, the director also knows that no wound is more toxic than a friend’s betrayal. There will be blood in Gone Girl, but some of the most startling moments are glancing — Amy’s quick kiss that includes a lip bite — and claustrophobic. What can be more ominous than the proximity of two people who are supposed to be in love but may have murder in mind?

Any readers, as they submerge themselves into a novel, automatically make the movie version in their heads. They cast it, too. For Gone Girl, they imagined Affleck as the only Nick, the way Gone With the Wind’s first readers preemptively saw Clark Gable as Rhett Butler. Good old Ben Affable, with his softness and weaselly charm, not to mention the cleft in his chin, seemed an ideal fit for the likable, not totally trustworthy Nick. The actor has played the bluff, fervent lover before, most notably in a terrific 1997 Kevin Smith rom-com called, yep, Chasing Amy; and in The Company Men he was the smug suburbanite who gets a comeuppance when he loses his job. It’s no surprise that Affleck slips into the role with the nervous aplomb of a man who starts to realize that the stroll he’s taking may lead to his own hanging.

For Amy, many readers envisioned Cate Blanchett or Charlize Theron; each could play a blond vixen capable of seducing and scaring a husband. But instead, the role went to the lesser-known Rosamund Pike. (Among her roles in Hollywood films: Andromeda in Wrath of the Titans and Tom Cruise’s helper in Jack Reacher.) Pike’s relative unfamiliarity to the mass audience allows her to draw Amy in careful cursive on a blank slate. We know of Pike’s Amy only what we see here: She is pretty, poised, always alert, ready to flash the witty remark that illuminates or scolds. She lives inside Amy’s brilliance, suggesting that the sunniest face can harbor the darkest intent.

In a movie of subtle tones and wild swerves, Pike expertly mixes a cocktail of hot and cold blood. She is the Amazing Amy you could fall for, till death do you part.

Note: An earlier version of this post misspelled the name of the actor Scoot McNairy.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com