An anniversary likes a round number, but 9/11 doesn’t always give us that. It’s the same awkwardness that Jeffrey Kluger described in the pages of TIME’s Sept. 17, 2007, issue: “A sixth anniversary is an awkward thing, without the raw feeling of a first or the numerical tidiness of a fifth or 10th,” he wrote. “The families of the 2,973 people murdered that day need no calendrical gimmick to feel their loss, but a nation of 300 million — rightly or wrongly — is another matter.”

Here are 13 essential stories on Sept. 11 from TIME’s archives, originally compiled for the event’s 13th anniversary.

If You Want to Humble an Empire. Sept. 14, 2001.

TIME’s editors had just a few days to pull together the entirety of the Sept. 14, 2001, issue. Much of that work fell to Nancy Gibbs, then a senior editor and now the magazine’s editor, who wrote a story that filled nearly every page. The piece is a recounting of what happened that morning, not only to the President and the hijackers, but also to those who were in the wrong place at the wrong time and those who went there later, to help.

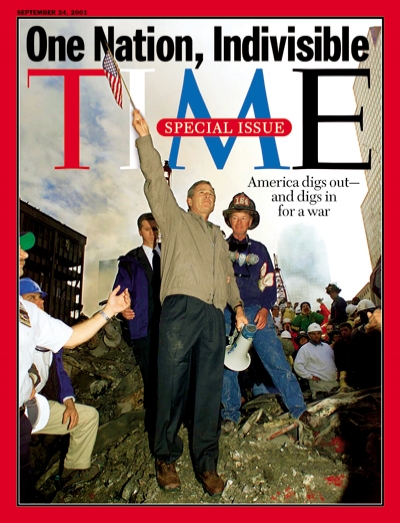

Mourning in America. Sept. 24, 2001.

By Sept. 24, 2001, there had been some time — not much, but some — to understand the scale of the day. The “One Nation, Indivisible” issue of TIME brims with the images that are most often remembered when thinking back to that day: President Bush, the missing posters, the flags. But there are also the moment-of memories that, for most of us, have likely faded to gray. The 1-800 numbers to call for information about helping; the 1-800 numbers to call if you were the one who needed the help. Once again, Nancy Gibbs wrote the issue’s cover story, a look at the national mood as the new reality set in:

In a week when everything seemed to happen for the first time ever, the candle became a weapon of war. Our enemies had turned the most familiar objects against us, turned shaving kits into holsters and airplanes into missiles and soccer coaches and newlyweds into involuntary suicide bombers. So while it was up to the President and his generals to plot the response, for the rest of us who are not soldiers and have no cruise missiles, we had candles, and we lit them on Friday night in an act of mourning, and an act of war.That is because we are fighting not one enemy but two: one unseen, the other inside. Terror on this scale is meant to wreck the way we live our lives–make us flinch when a siren sounds, jump when a door slams and think twice before deciding whether we really have to take a plane. If we falter, they win, even if they never plant another bomb. So after the early helplessness—What can I do? I’ve already given blood—people started to realize that what they could do was exactly, as precisely as possible, whatever they would have done if all this hadn’t happened.

We’re Under Attack. Dec. 31, 2001.

As part of the 2001 Person of the Year issue honoring New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, TIME put together an extensive oral history of Sept. 11:

GIULIANI: I go up to [Fire Chief Peter]Ganci and I say, “What should I communicate to people?” He says, “Tell them to get in the stairways. Tell them our guys are on the way up.” And then he looks at me and says, “I think we can save everybody below the fire.” What he is telling me is, they’re gone. Everybody above the fire is gone. He says people are not panicking. They’re moving fast. I grab his hand, shake it and say, “Good luck. God bless you.”

A Miracle’s Cost. Sept. 9, 2002.

On the first anniversary of the attacks, TIME looked at the lives of 11 people who had been deeply affected by 9/11. Though others are more famous, from the President to the head of the Victim Compensation Fund, Genelle Guzman-McMillan’s story is equally worth remembering. John Cloud profiled the last person to be found alive in the rubble of the Twin Towers, a Port Authority employee, and finds that survival is far from simple:

“For Judy,” says Gail [LaFortune], using her cousin’s middle name, as do those who grew up with Genelle in Trinidad, “there’s a sense of…of misplaced things, of misplaced parts of her life.” If that’s true, how does Genelle Guzman-McMillan find herself again? It turns out there is no shortage of people who want to help create a carefree, well-centered version of Genelle—and an inspirational Sept. 11 tale for the rest of us: Victim miraculously lives, turns to God, finds true love (in July, she and longtime boyfriend Roger McMillan had a free “dream wedding” arranged by Bride’s magazine and CBS’s The Early Show, an event both then covered as news). But her story isn’t so simple. People say Sept. 11 was a crucible for our nation, which may or may not be true, but it was doubtlessly a crucible for the person you see in the pictures on this page. The question is, Who emerged from that crucible? Why did the last survivor survive?

The World According to Michael. July 12, 2004.

As the post-Sept. 11 mood of national unity began to show cracks in the years after the attacks, perhaps no one better exemplified that change than divisive documentarian Michael Moore, whose film Fahrenheit 9/11 remains the top-grossing documentary in movie history. Richard Corliss profiled the filmmaker for a cover story shortly after it hit that milestone:

“Was it all just a dream?” Michael Moore poses that question at the start of Fahrenheit 9/11, his docu-tragicomedy about the Bush Administration’s actions before and after Sept. 11, 2001. Moore’s tone isn’t wistful; it’s angry. He’s steamed about the Florida vote wrangle of 2000, the Supreme Court decision to declare George W. Bush President of the United States, the policies of Bush’s advisers and especially what he sees as the deflection of a quick, vigorous search-and-destroy mission against Osama bin Laden into an open-ended war on terrorism—”You can’t declare war on a noun,” Moore said last week—that spawned a dubious and costly invasion of Iraq.

Halting the Next 9/11, Aug. 2, 2004

Romesh Ratnesar parsed the 567-page 9/11 commission report and found it meticulous — but questioned whether the knowledge it contains can possibly make a difference:

In the long run, making America and its allies safe again will require far broader changes than even the 9/11 panel was empowered to propose. In the meantime, the U.S. has little choice but to brace itself for the possibility of another strike. “We do not believe,” the commissioners write in the report’s conclusion, “that it is possible to defeat all terrorist attacks against Americans, every time and everywhere.” In that sense, the 9/11 commission’s legacy may ultimately be determined by how long the U.S. can deter the inevitable.

The Class of 9/11. May 30, 2005.

Kristen Beyer came to West Point because she was recruited for swimming, but mere weeks had passed before it became clear that the service she had signed up to give after graduation would not be in a peacetime army. Nancy Gibbs and Nathan Thornburgh profiled Beyer and two of her classmates on the eve of their graduations:

Cadet after cadet spoke up. Terrorists attacked us, they said. If you were on the fence even in the slightest, if you weren’t 100% sure you wanted to be in this fight, you shouldn’t be here at all. Beyer didn’t know those cadets or whether they knew her or whether they saw her as a laid-back swimmer type without a soldier’s steel. Still, their comments cut straight through her and destroyed the frail truce she had made with West Point. “I just shut up,” she says. “But I was so angry. ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ I asked myself. The attitude was, If you didn’t grow up just dying to be in the military, you’re worthless.”

It was the beginning of Beyer’s darkest time at West Point. “Every day I just hated myself for staying. I hated everybody else.” Everyone except her teammates and Huntington, whom she had talked into staying with her. “We got much closer. I could use her as a shoulder to cry on, and she could use me the same way,” Beyer says. Ultimately, she decided that the Army wasn’t going to change. She had to.

The Day That Changed… Very Little. Aug. 7, 2006

Much of the media narrative after 9/11 was about how pop culture was going to become more sincere and more serious. Then a few more years went by, and James Poniewozik wrote about how those predictions turned out to be false:

Still, saying that 9/11 has entered pop culture is not the same thing as saying that 9/11 has changed pop culture. The disaster movie, the docudrama, the inspirational war story–those are not exactly innovations. There were predictions just after the attacks that pop culture would become more patriotic or more nostalgic or more introspective. Instead, it has just become more of what it was before–violent, irreverent, licentious and so on. 24 is a great show, but you can trace its ice-blooded do-what-you-gotta-do-ism back to Dirty Harry, not Donald Rumsfeld. It’s hard to see how any post-9/11 movie has hit on the nobility, banality and absurdity of war in a way Saving Private Ryan didn’t. On Three Moons Over Milford, a new comedy-drama on ABC Family, ordinary people change their lives after the moon breaks into three pieces, threatening Earth. But it’s a series on a modestly rated cable channel. Five years after 9/11, rethinking your priorities in the face of mortality is now niche programming.

Why the 9/11 Conspiracies Won’t Go Away. Sept. 11, 2006.

On the fifth anniversary, Lev Grossman investigated why so many people want to believe that the rest of us are missing something about what happened on Sept. 11:

There are psychological explanations for why conspiracy theories are so seductive. Academics who study them argue that they meet a basic human need: to have the magnitude of any given effect be balanced by the magnitude of the cause behind it. A world in which tiny causes can have huge consequences feels scary and unreliable. Therefore a grand disaster like Sept. 11 needs a grand conspiracy behind it. “We tend to associate major events–a President or princess dying–with major causes,” says Patrick Leman, a lecturer in psychology at Royal Holloway University of London, who has conducted studies on conspiracy belief. “If we think big events like a President being assassinated can happen at the hands of a minor individual, that points to the unpredictability and randomness of life and unsettles us.” In that sense, the idea that there is a malevolent controlling force orchestrating global events is, in a perverse way, comforting.

Death Comes for the Terrorist. May 20, 2011

David Von Drehle reported on the killing of Osama bin Laden, from President Bush’s 2001 uttering of the words “dead or alive” to President Obama’s finding himself in the Situation Room:

Osama bin Laden, elusive emir of the al-Qaeda terrorist network, the man who said yes to the 9/11 attacks, the taunting voice and daunting catalyst of thousands of political murders on four continents, was dead. The U.S. had finally found the long-sought needle in a huge and dangerous haystack. Through 15 of the most divisive years of modern American politics, the hunt for bin Laden was one of the few steadily shared endeavors. President Bill Clinton sent a shower of Tomahawk missiles down on bin Laden’s suspected hiding place in 1998 after al-Qaeda bombed two U.S. embassies in Africa. President George W. Bush dispatched troops to Afghanistan in 2001 after al-Qaeda destroyed the World Trade Center and damaged the Pentagon. Each time, bin Laden escaped, evaporating into the lawless Afghan borderlands where no spy, drone or satellite could find him. Meanwhile, the slender Saudi changed our lives in ways large and small, touched off a moral reckoning over the use of torture and introduced us to the 3-oz. (90 ml) toothpaste tube.

Portraits of Resilience. Sept. 19, 2011

Ten years after 9/11, TIME featured interviews with 40 people who led, who helped, who survived. The website that accompanied the print project won an Emmy award in 2013; it can be found online at http://content.time.com/time/beyond911

The One World Trade Center panorama. March 6, 2014.

As One World Trade Center neared completion, Josh Sanburn wrote about the new building, a dozen years in the making :

But the long wait was also the result of a nearly impossible mandate: One World Trade Center needed to be a public response to 9/11 while providing valuable commercial real estate for its private owners, to be open to its neighbors yet safe for its occupants. It needed to acknowledge the tragedy from which it was born while serving as a triumphant affirmation of the nation’s resilience in the face of it.

“It was meant to be all things to all people,” says Christopher Ward, who helped manage the rebuilding as executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. “It was going to answer every question that it raised. Was it an answer to the terrorists? Was the market back? Was New York going to be strong? That’s what was really holding up progress.”

Remains of the Day. May 26, 2014

When the 9/11 museum opened this spring, Richard Lacayo looked at the way it preserves the past and serves the future:

The completion of the museum is an important moment in the imperfect reclamation of Ground Zero, a place where years ago grief swept the table and which is slowly coming back to life. You could say that every visitor will now be a kind of recovery worker, returning the site to normality simply by being there, helping in a small way to take back that haunted space.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com