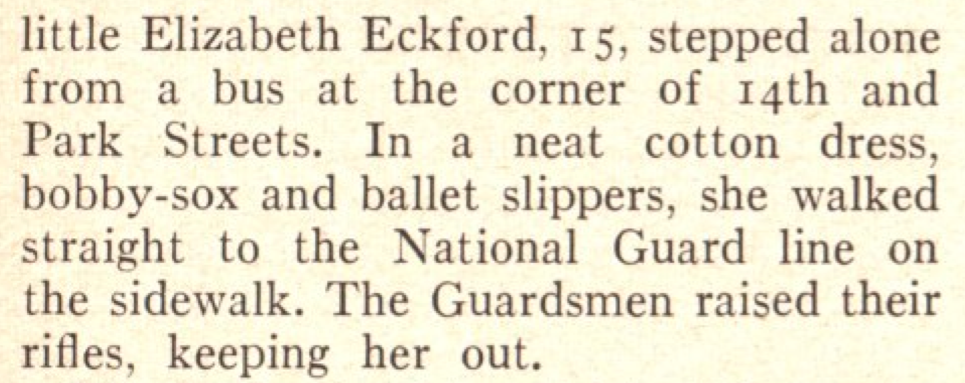

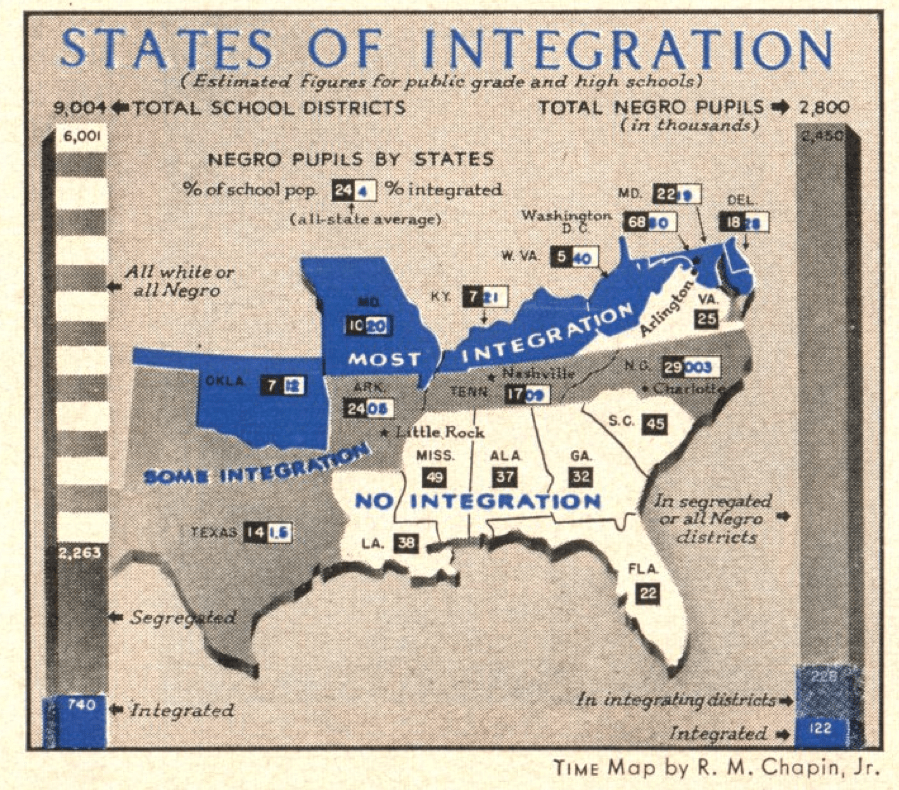

The Little Rock crisis sounds like a story from ancient history: on this day in 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called in the state’s National Guard in order to stop nine African-American high-school students from entering Little Rock High School on the first day of class. Weeks would go by before President Eisenhower sent in paratroopers to protect the children and nearly a decade before the 1964 Civil Rights Act — which gave the federal government the authority to require desegregation — put an end to the total resistance embraced by the political leaders of the South. The chart shown below was part of a Sept. 23, 1957, TIME “report card” on school integration; it makes clear that, though the Little Rock crisis came years after the Supreme Court ordered the end of segregation, a wide swath of the South was still stuck in the past.

The civil rights movement and the leadership of LBJ won passage of the historic l964 Civil Rights Act, which gave the government broad powers to end discrimination. By 1970, as a result of that act, leadership from the White House and strong support from the Supreme Court, the South had the most diverse schools in the nation. The fight for integration had been resolved, or so it might have seemed.

And yet that past is still very much present. Leadership evaporated and resistance grew in the 1970s, and segregation returned. Earlier this year, for a report on the history of desegregation for that I co-authored for the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, I looked at recent school-integration figures. The numbers were dispiriting:

Unhappily, segregation has only been increasing across the U.S. since the 1990s. Though the situation in the South is still much better than before 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education required integration, we have lost the progress made in the last 40 years. During that time, the U.S. Supreme Court, the institution that opened the desegregation struggle, has slammed the door for many communities, with rulings that have dismantled even very successful desegregation plans. The Obama administration has done little to change a deepening isolation as the nation’s schools become half nonwhite.

One of the most common objections to desegregation policies is that there is nothing magic about sitting next to white students, implying that desegregation is about just skin color. But segregation is usually double segregation both by race and poverty — and sometimes triple segregation, by ethnicity, poverty and language — and is deeply related to the most important factors that make a school strong, like experienced teachers, well-prepared students and a demanding curriculum. Integrated schools have higher graduation rates and their students have greater success in college. Those things are magic.

Why can’t we make schools better without addressing segregation? That was the idea of the Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” Plessy decision way back in 1896 and it never worked. Many educators still claim that they can do it, pointing to the rare school that has very high test scores or falling for lies as in Atlanta and Washington. But, while the vast bulk of the money the federal government has put in public schools has gone to the cause of raising achievement in high poverty schools — almost nothing for desegregation for the last 33 years — the schools remain profoundly unequal. A half century of research shows that integrated schools are better learning environments. One recent econometric analysis showed, for example, that five years of integrated eduction was linked to a 14% increase in the probability of graduating from high school . Minority students gain, are more like to graduate and go to college. White and Asian students do not lose in achievement — and all students gain in their preparation to live and work together in what will be a profoundly multiracial society in which we will all be minorities.

Desegregation doesn’t solve all problems — there are many roots of inequality — but it is far better than segregation. It is time to recall the struggles of the Civil Rights era and to put our imaginations to work to bring more young students of color into good schools, to stop housing discrimination and to raise more children of all races in our segregated and unequal society in equal and integrated schools.

Several years ago I visited the Museum of Segregation in Soweto, South Africa. I loved its mission: putting segregation “in a museum where it belongs.” I wish that were true in the USA. Unfortunately, we are celebrating civil rights in museums and monuments while quietly accepting the spread of segregated and unequal schools. It’s time for this generation to stop celebrating and get to work.

Gary Orfield is co-director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA

Read TIME’s full 1957 profile of Orval Faubus, for free, here: What Orval Hath Wrought

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com