Correction appended, August 25

It’s probably every teenager’s dream to get paid for snapping iPhone pictures. Instead of selfies, though, David Soloff is seeking pictures of fruit carts, health clinics and remotely located schools. His startup is hoping to leverage the vast proliferation of smartphones—and our insatiable desire to take photos with them—in order to bring real-time economic data to the masses.

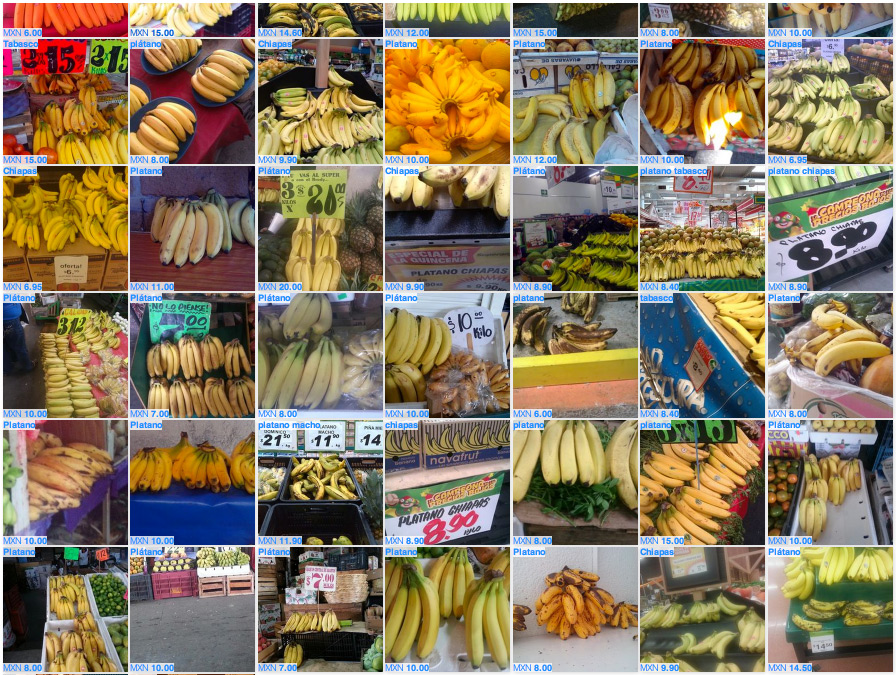

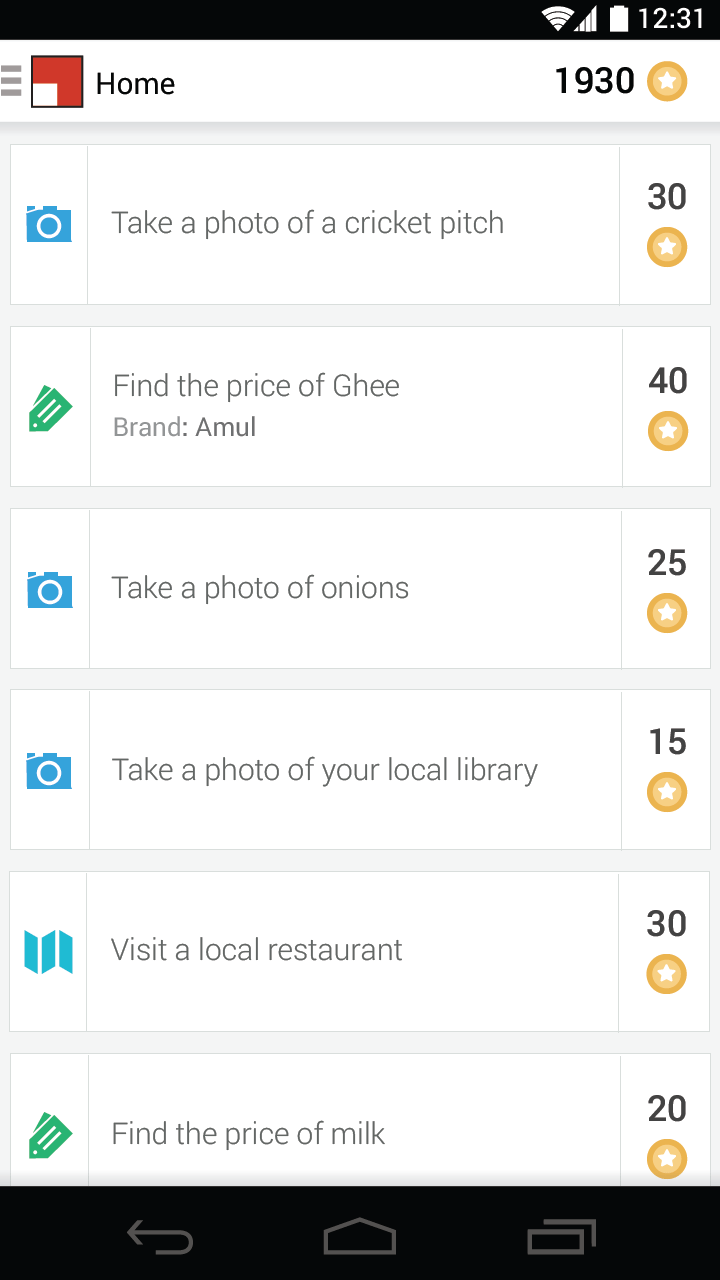

The new company, called Premise, tracks economic indicators by enlisting armies of local residents to record data about their communities, like the price of oranges at a local market or the physical condition of a local health clinic, via an Android app. Premise pays the photo-takers up to 15 cents for each “observation,” which can be a picture or other data point. The company aggregates all the individual observations to derive broader insights about inflation and consumption shifts in different countries, then sells the data to financial institutions.

Premise’s aim is to provide important economic metrics faster than government agencies, which often only release data in weekly or monthly intervals. The company is currently gathering data in 50 cities across four continents, including locations in Argentina, China and the United States.

“What people experience in their day-to-day lives is frequently really, really different from what the official government or news bureau or stats-gathering agencies tell them about their lives,” says Soloff, Premise’s CEO. “By the time those official numbers come out, the world’s probably changed a lot.”

Soloff points to countries like Argentina — where Premise and a variety of economists have projected inflation to be increasing much faster than the government says it is — as an example of a place where private data sources can be more reliable than official figures. In other countries, such as India, where onion prices leapt 190% in 2013, food prices are incredibly volatile and government-released figures can’t keep up with the rapid changes.

“Almost certainly, in a lot of countries, the government is lying about price changes,” says Gary Burtless, an economist at the Brookings Institution. “It would be useful to know, to ordinary people and to businesses, what the real inflation is.”

How does Premise ensure that its figures are accurate? To devise its economic models, the company has brought on advisors whom Soloff calls the “adult supervision.” Among them are Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist and Alan Krueger, the former chairman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. To guarantee that data are collected accurately on the ground, Premise vets local residents by giving them test assignments, then evaluating their performance before committing their observations to the official dataset. The company recruits new workers via social media, online job boards and college campuses.

“It’s not an open cast call,” Soloff says. “These are students or people on the way to jobs or people who are doing the weekly shopping for their families at the market.”

So far, Bloomberg and Standard Charter Bank have signed on to receive Premise’s data, in addition to other financial institutions that Soloff declined to disclose. The company is currently unprofitable, but it has raised $16.5 million in venture funding from bigtime backers like Google Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz.

Soloff isn’t the most likely man to head a high-tech San Francisco data firm. He studied Near Eastern linguistics as an undergrad at Columbia University and has a master’s in history from the University of California, Berkeley. But Soloff believes his humanities background gives him an edge in Silicon Valley.

“I’ve always been interested in systems, how things work,” he says. “Language systems, social systems, financial markets have always fascinated me.”

It also helps that Soloff had a two-year stint as a quantitative analyst at a Wall Street investment bank and co-founded Metamarkets, an analytics tool used for programmatic online advertising.

Soloff’s long-term goal is to expand the scope of Premise into a real-time financial pulse that can provide immediate economic data to not only wealthy investment institutions but also regular citizens. Other platforms have similar aims — the Billion Prices Project, started by a pair of MIT professors, gathers online price listings from more than 70 countries to predict inflation trends from around the world. Such initiatives “have a real value to consumers and businesses,” the Brookings Institution’s Burtless says.

But the devil is in the data, of course. Some economists question whether locally recruited residents can reliably document data for an entire community or country.

“Surveys are of no value unless we can be assured by some means that they are representative of the underlying population,” Barry Bosworth, another economist at the Brookings Institution, said in an email. “The survey will reflect all the biases of the reporter who decides what prices to report. We may use the Internet more in the future to collect data but it will have to be used with some structure to assure that the individual quotes are representative of an even larger underlying population.”

Premise spokesperson Sara Blask said in an email that the company’s contributors capture observations at predetermined locations and intervals to assure that the sample is indeed accurate. “In this sense we are the opposite of crowdsourcing,” she said.

Premise’s dataset should grow more robust and useful as it racks up more observations.

In five years’ time, Soloff envisions millions of people around the world submitting photos and other information to Premise. He believes such a cascade of data could help keep governments more honest in the future. “Rather than relying on the official story, so to speak, [people] have an alternative read that’s generated by the citizens just like them,” he says. “We don’t need to tell them what’s happening—it’s the opposite.”

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the number of locations where Premise has launched. The company is collecting data in 50 cities.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com