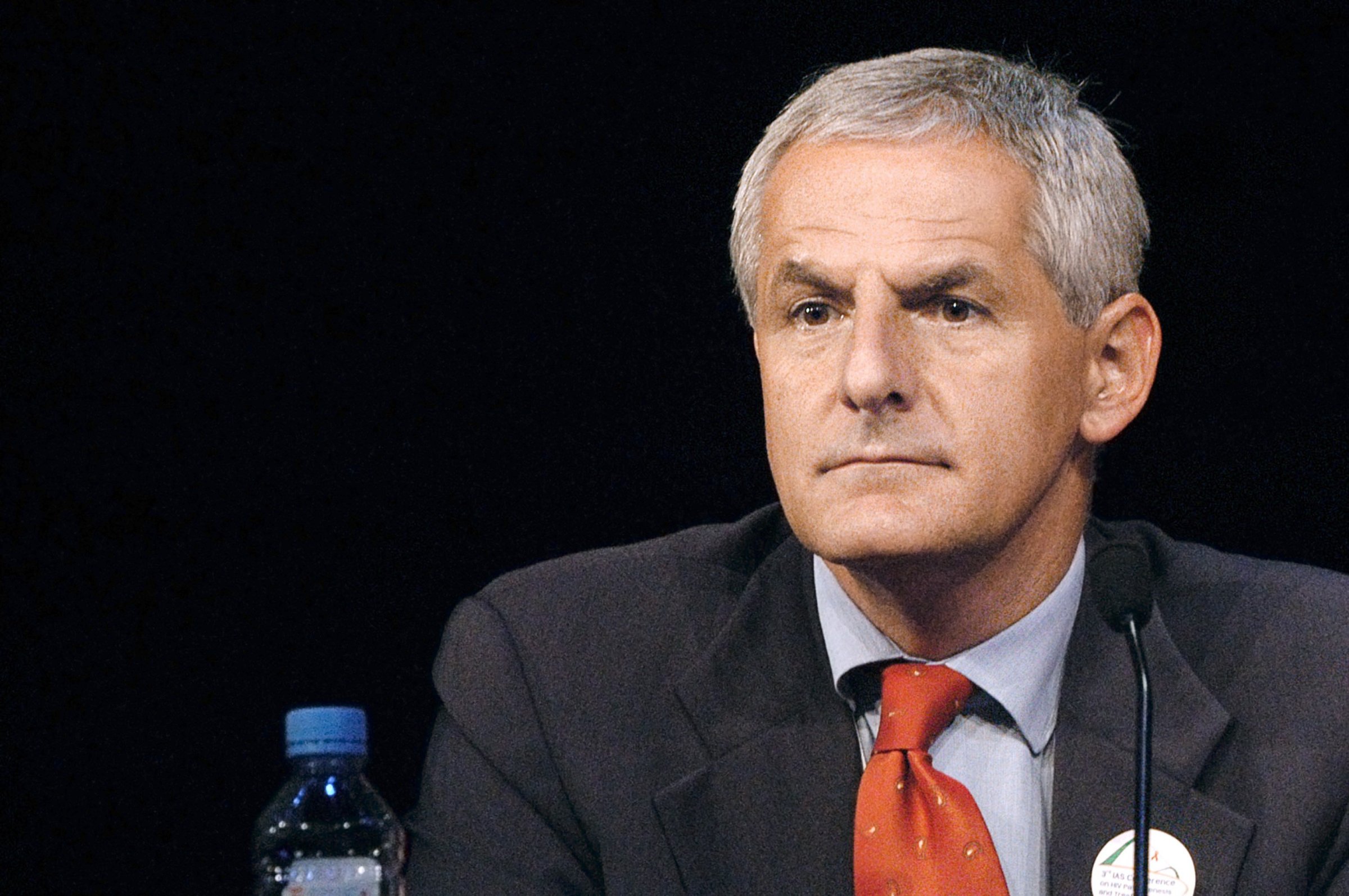

Late last night, a terrific HIV vaccine researcher, Wayne Koff, sent me a quick note, indicating Joep Lange perished aboard the jet senselessly shot down over Ukraine. I reeled. Joep was one of the group of “Young Turks” from Amsterdam, amazing AIDS researchers that in the 1990s led the way to our modern treatment era.

This morning’s news is still uncertain, but it seems Lange was on board along with some 100 of his Dutch compatriots, and many of the passengers shared an ultimate destination – the twentieth International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia. Some probably highly premature news accounts indicate a third of those shot out of the sky were en route to the conference. One additional has been confirmed – Glenn Thomas, AIDS specialist in the World Health Organization communications office.

There was a time when we convened in these meetings and whispered the names of friends, colleagues, and loved ones that wouldn’t be coming this year because they died of AIDS. In our gatherings in the 1980s, grief hung like a curtain over everything, alongside anger over the way governments were responding, the lack of funding, the stigma, and so many other aspects of what it was like to live in the World of AIDS before there was treatment. We fought through the mourning to get the job done, whatever that job might be: activist protesting, scientific investigation, fundraising, even journalism. The great oratory leader of the early AIDS fight Jonathan Mann would whip us into a fever of determination to stop discrimination against people with AIDS, fight for research funding, and find a cure for the devastating disease. Jonathan, who started the first global AIDS program at WHO, was the early pandemic cheerleader, pushing everybody forward, encouraging teams of scientists to work together in ways biologists and clinicians never previously had, for any disease struggle.

The Young Turks from Amsterdam were a special breed. There were so few of them yet they accomplished a long list of spectacular breakthroughs in understanding how HIV disrupted the human immune system, smart ways to prevent transmission of the virus among drug users, careful but rapid drug discovery and testing. Joep and Jaap – two prominent Dutchmen we foreigners had trouble pronouncing. What is the world is the difference in saying Joep Lange and Jaap Goudsmit? We marveled at the pragmatism of the Dutch. To put it bluntly, they got the job done.

In 1996 the one and only joyous AIDS Conference convened in Vancouver – a meeting marked by announcement of successful combination therapy that knocked the dastardly virus down to levels undetectable in blood. There was hope for a cure, thanks in large part to the Dutch work. Some dared to speak of eradicating HIV all together.

Two years later, as hundreds of thousands of HIV-positive men and women living in wealthy countries were thriving on those treatment combinations, hope dominated the pandemic, until 1998 when Swissair Flight SR11 crashed off Nova Scotia, killing all on board. Among them, Jonathan Mann and his new wife, AIDS vaccine researcher Mary Lou Clements. Their sudden loss felt like a kick in the gut for the world AIDS community.

Here we are, sixteen years later, facing airline tragedy again. As I write this in haste we don’t have more names and the scale of the AIDS community’s loss is unclear. But the loss of one is tragedy.

Like so many of the great AIDS scientists that toiled through the years of extreme loss and urgency before there was effective treatment, Joep Lange absorbed the political dimensions of the pandemic, and gained the skills necessary to translate lab and clinical findings into high-level battles inside the United Nations and across the global stage. He became a leader, in the fullest sense of that word. Like Jonathan Mann, Joep blended science, medicine, and an activist spirit to help bring the life-sparing medicines to people in all of the world – not just rich countries.

The last time Joep and I spent time together we argued, I’m sorry to say. And I may have been completely wrong, he completely right. The saga we argued about hasn’t played out yet. Joep believed without hesitation that effective treatment, “is like a vaccine,” as he put it. The global epidemic could be stopped, he said, simply by getting every HIV+ person on the planet put on an effective regimen of treatment. Once on medicines, he insisted, the load of viruses in their blood, vaginal fluids, and semen would drop so low that they would not be contagious. And that, he said with a grin, will be the end of AIDS. I was skeptical – there were too many cases of drug resistance, non-adherence to treatment, supply chain failures to deliver vital drugs to remote or impoverished areas. I resented use of the word “vaccine” to describe universal treatment – we still desperately need an actual HIV vaccine, I insisted.

I want Joep’s optimism about eliminating AIDS through treatment to win out. I want to be wrong.

I just wish Joep was going to be around to see the great experiment play out.

A Tweeter asked me if the loss of Joep, Glenn, and other AIDS researchers and activists possibly on board MH17 would prove a major set-back in the fight against AIDS. No, I said. One of the glories of the AIDS community is that its bench is deep, its talents enormous, and its sorry history of processing grief and moving on is unparalleled. The dead, as has always been the case since this awful virus emerged in the late 1970s, will be mourned. And then energies will be mustered, to get the job done.

Until there is a cure.

Laurie Garrett is a senior fellow for Global Health at the Council on Foreign Relations. This essay also appeared on http://lauriegarrett.com/blog/.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com