Ten years ago, I was catapulted headfirst into a gutting grief by the sudden death of my six-year-old daughter, Charlotte. I was desperate for guidance. Conventional wisdom at the time relied upon Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief — denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance — developed in the 1960s while she was working with terminally ill and aging adults. These have become the accepted route for those facing their own death and those grieving the loss of loved ones.

It’s time we rethink grief.

Delving into resources that detailed “grief work,” I found no discussion of joy or happiness as an endpoint, no allusion to a deepening of heart and mind, and little talk of the freedom that settles into one’s soul when all but the most basic desire are stripped away. Yet, that is the closure I came to: That it is entirely acceptable and possible to find joy, happiness, and a more deeply fulfilling life than one had prior to a devastating loss.

At the time, the mere thought of wanting to want to find a place of resilience made me feel I was doing the whole thing wrong. Surely, if I did not stay in a persistent state of woe then it must be due to denial, conflicted emotions about Charlotte, or an inability to feel.

In those early months of grief that stretched into years, I was encouraged by the reserves of bravery and resilience I discovered I had, and equal parts concerned that I wasn’t overcome 24/7. I perceived I was doing it differently and isolation pervaded much of my grief. Moving back into the natural rhythm of life in the face of such a ruining loss just felt plain old wrong. Did going forward make me a callous and unfeeling monster? This brought on more investigative therapy.

Today, I’ve largely made peace with the early death of my daughter. By no means easy, it has not been the relentless march that I had feared. Psychotherapy and grief groups did not uncover buried levels of denial. In our home there were plenty of pizza dinners and hollow conversations, but I never did have the gothic meltdowns or unrelenting mourning. I was sometimes happy. Not to say that I wasn’t deeply sorrowful. I wept daily and struggled with thoughts of where my daughter had gone. My belief system was called into question regularly.

Recently I was introduced to Dr. George Bonanno’s explorations of grief and his book, The Other Side of Sadness. His basic premise is that loss pervades the animal kingdom and none of us moves through life untouched by it, yet we are programmed genetically to be resilient. Even ten years out, his work offered a great sense of relief and comfort. Maybe I was not the outlier I suspected.

It is impossible to be unchanged by grief. It deepens us. Perhaps hardens us, but also opens doors and softens bits of us, as well. Mine is a story of moving through the pain of losing a loved one I thought I could not live without and coming back on the other side with a better appreciation for life, as a more deeply loving and engaged human being. I would give all of my hard-won wisdom back in a nanosecond if it would mean the safe return of my daughter (hello, bargaining), but that is not to be.

We are marked by grief for life, yet if we are open to its gifts, we can be healed by it. Ralph Waldo Emerson famously said, “Sorrow makes us all children. Destroys all differences of intellect. The wisest knows nothing.” Laid bare, grief gives us an opportunity to rebuild and grow up a second time. We may find our way to new lines of thinking. These can ultimately leave us comfortable in our own skin in ways we had never thought possible.

Consider that we do ourselves a disservice by not working hard enough to stand up, move forward, and be strong and courageous. We give ourselves too much permission to suffer. I don’t for one second mean to imply that people should deny emotions of any sort while experiencing the grief process. It comes in different forms for different people and lasts for varying amounts of time. But what I do believe is the place of relative comfort with the loss comes more quickly than conventional wisdom would have led us to believe. And yes, that place does come for almost everyone.

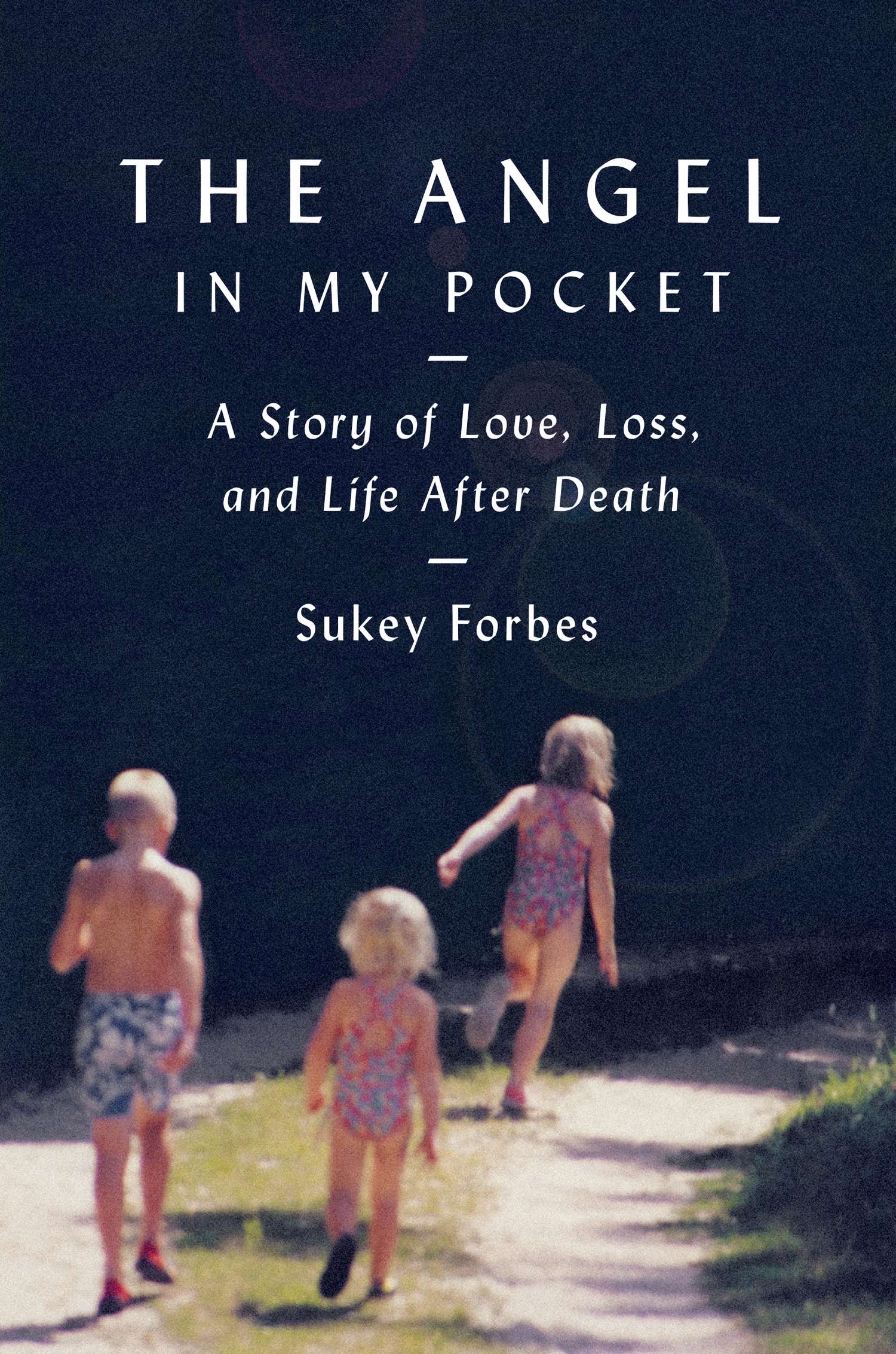

Sukey Forbes runs an art, antiques, and interior design company near Boston. Her book, The Angel in My Pocket, was recently published.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com