It was just 18 months ago that we were living in the “Year of the MOOC.” Massive open online courses—MOOC for short—were supposed to revolutionize the way people learned and deliver high-quality education to the masses. But the idea faced a tough 2013. The co-founder of Udacity, an early pioneer in free online education, admitted that his company initially had a “lousy product,” while studies showed that hardly any students were actually completing the courses offered by such services at all.

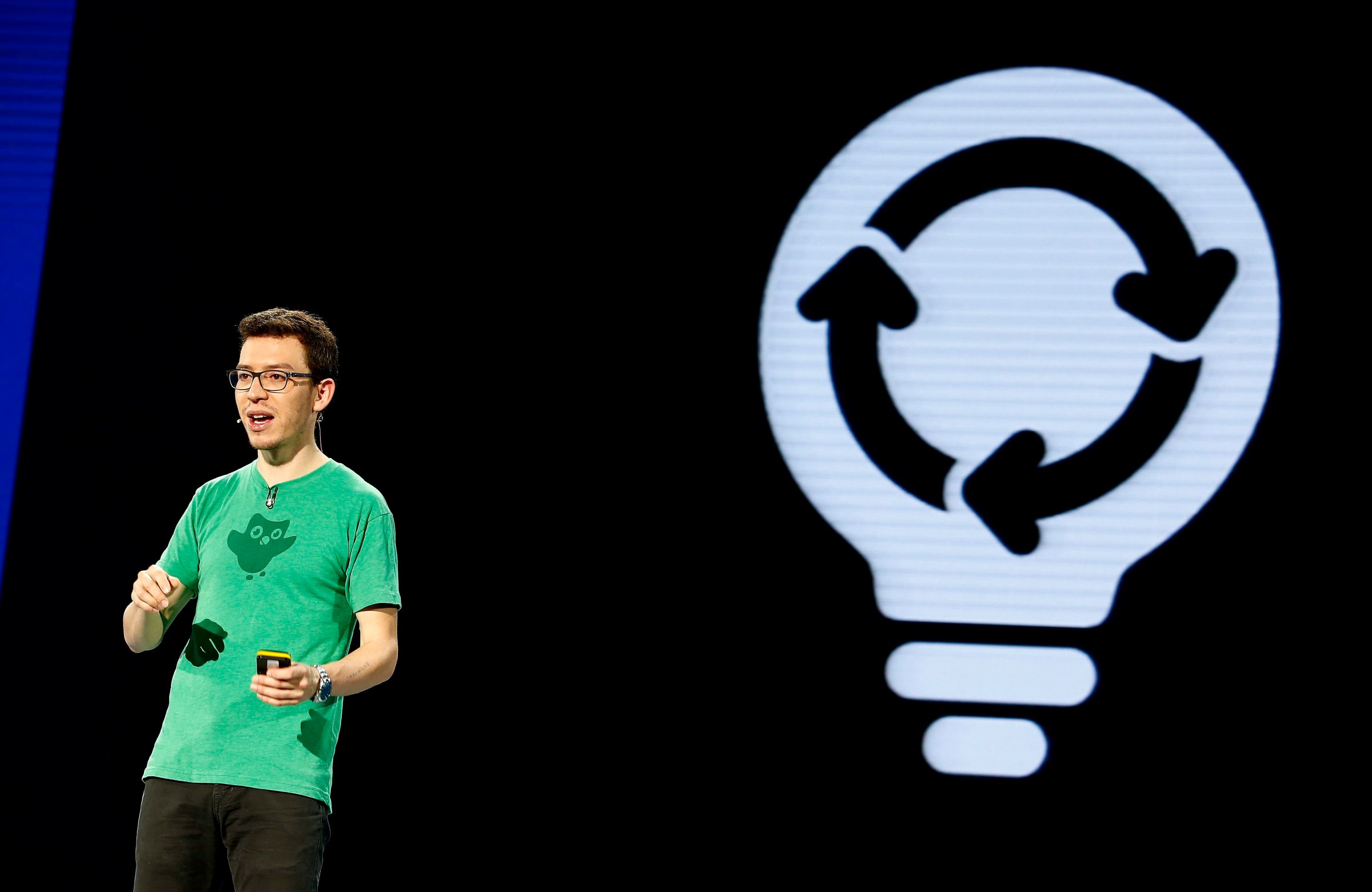

Luis von Ahn, the co-founder and CEO of language learning service Duolingo, says MOOCs make little sense for the digital world. von Ahn runs what is arguably the hottest educational tool online at the moment, but he’s also a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University. Even he admits that lectures, especially delivered via webcast, can be pretty boring. “You take a lecture that’s not all that great and put it on video, it’s actually going to be worse,” he says. “Typically, the things that succeed the most online are the things that are better online than offline. Think about email versus mail.”

von Ahn believes he has developed a platform that can indeed be better online—and on smartphones. Duolingo, which turns two years old this week, offers bite-sized lessons in French, Spanish, English and several other languages for beginners and intermediate-level speakers. Users learn vocabulary words, grammatical structures and even proper pronunciation by speaking into their device’s microphone. The service guides students through a battery of challenges, awarding points and badges for correct answers. Users can compete with friends who are learning the same languages.

The concept of learning a new language through software is hardly revolutionary, but it’s Duolingo’s mobile app that sets it apart. Six months into the company’s existence, Duolingo had 300,000 active users, all on its website. In the year and a half since it launched a mobile app for iOS, that number has leapt to 13 million, more than MOOC platforms Udacity, edX and Coursera combined, according to usage figures released by those firms. 85% of these users are learning with the mobile app, which Apple named the App of the Year in 2013. “One of the main ways to deliver education over the next 10 to 20 years is going to be through smartphones,” von Ahn says. “It’s the only way that this actually can scale. This is why we put so much effort into our apps as opposed to our website.”

The mobile approach has advantages both in the developed world—it’s easier to commit to a quick language lesson during lunch than block off an hour after work to sit at a desktop computer—and in emerging markets, where many people use smartphones as their primary computing device. “About 1 to 2 billion people do not have access to very good education,” von Ahn says, “but hundreds of millions of these people are very soon or already have access to smartphones.”

The son of two medical doctors, von Ahn grew up in Guatemala, a country with one of the lowest literacy rates in the world. He says Duolingo, which is free and doesn’t have advertising, is primarily aimed at those people who can’t afford to take a college course or buy expensive software like Rosetta Stone. “We’ve become zealots about providing free education,” he says. “We develop for the poor people.”

And yet, Duolingo is a for-profit business. To make money, the company gets its users to translate real news articles from sites like CNN and Buzzfeed into their native languages as a way to practice their English. Duolingo then charges these sites between two and three cents per word for the translations. von Ahn says the venture generates hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue per year, but Duolingo is not profitable. The company just began offering an English language proficiency test for $20 aimed at job seekers, but it’s not yet clear how many employers will accept a Duolingo certification as an alternative to more established (and expensive) programs. The company has raised $38 million in venture funding.

Whether people are actually learning new languages effectively with Duolingo is still an open question. von Ahn is careful not to oversell the capabilities of the service. The idea that a piece of software could make a person fluent in a foreign language in mere hours is, in his words, “bull—t.” “If you really want to become perfectly fluent, probably what you need to do is move to that country,” he says. “Learning a language is something that takes years.” Still, he says completing all the lessons in a language course in Duolingo is about the equivalent of taking an intermediate-level language course in college. A study commissioned by the company found that people learned as much taking Duolingo lessons in Spanish for 34 hours as they would in a semester of an introductory college class.

That doesn’t mean that apps are going to replace classrooms anytime soon. Though there’s great potential in educational tools built for the Web and for mobile, their usefulness varies greatly by subject, says Matthew Chingos, a fellow at the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. “If I want to learn about the history of the Ottoman Empire, it’s harder to imagine the really engaging version of that where you’re doing one-sentence interactions around a topic like that,” he says. “Is this going to replace the way things are done now? I don’t think it is. But can these tools be important supplements? I think they can.”

Duolingo, along with other web-native learning tools like the computer programming site Codecademy, have carved out an online learning experience that feels both simpler and more engaging than the typical MOOC, which essentially replicates the college lecture hall. von Ahn plans to focus on improving Duolingo’s adaptive learning capabilities, so that no two users will have the exact same lesson plan. The goal, he says, is for the app to perform more like a well-trained personal tutor than a pedantic professor.

Eventually, he sees Duolingo’s interactive learning experiences spreading to many other subjects. “A really good one-on-one tutor can teach a 10-year-old kid algebra in six months,” he says. “I think an app should be able to do that.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com