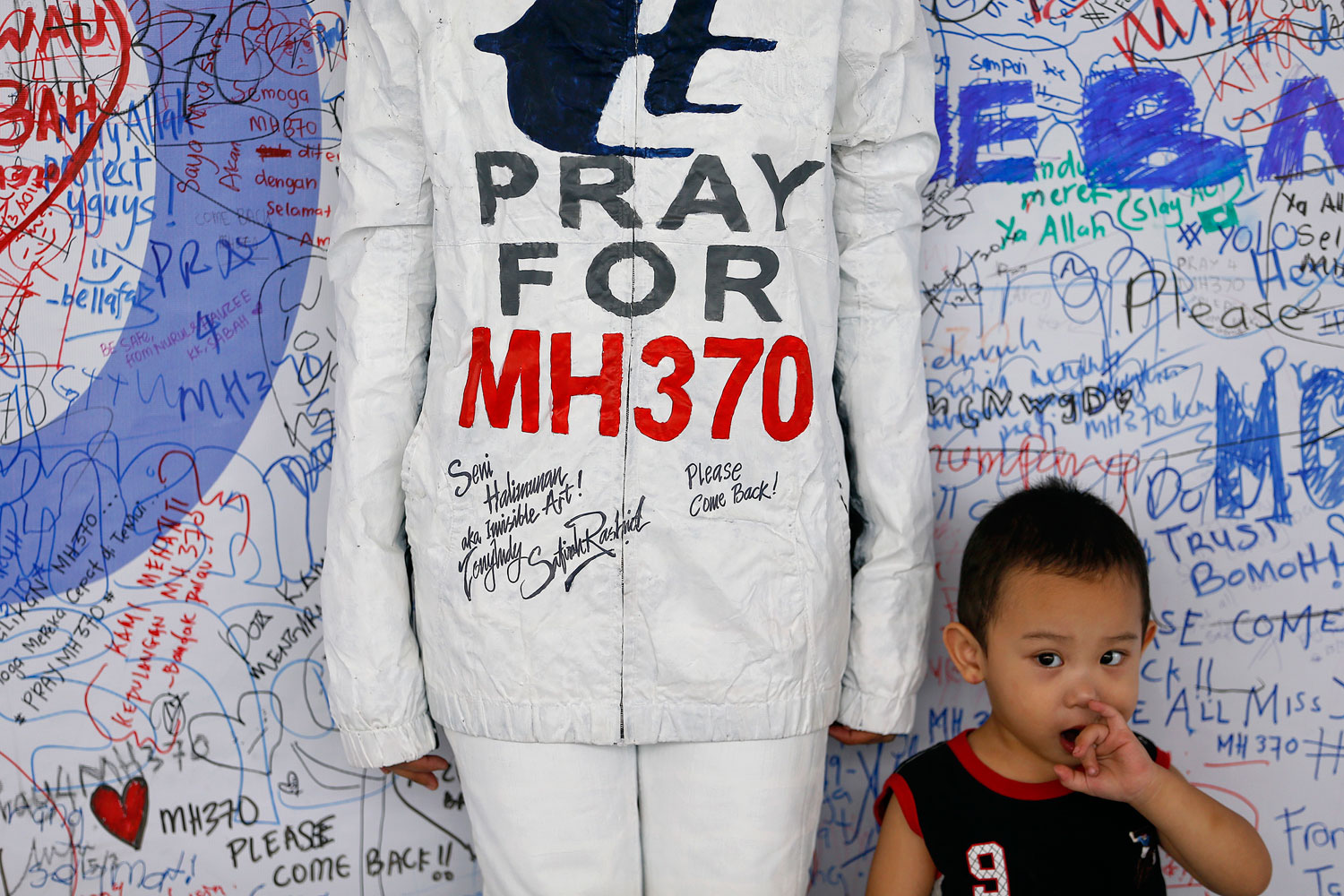

As the search for MH370 widens to some 30 million square miles, the failure of the Malaysian Air Force to identify the plane on radar has taken on new significance.

The number of nations involved in the search has been expanded from 14 to 25, and now includes Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, China, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia, Australia, France, the U.S and the U.K.

The huge area to be searched, and myriad nations to be coordinated, means fingers are being squarely pointed at the initial dawdling by Malaysia’s armed forces.

“Clearly they had let an unidentified aircraft pass through Malaysian sovereign territory without bothering to identify it; not something they were happy to admit,” writes aviation consultant David Learmount, who had previously decried “a chaotic lack of coordination between the Malaysian agencies.”

The Malaysian military spotted the missing jet passing through three military radars over the country’s far northeast, before it headed out over the Strait of Malacca. But despite its erratic behavior, the American-made F-18s and F-5 fighters on alert at Butterworth Air Force base sat idle.

Had the jets been scrambled, the world would have been saved a massive and extraordinary search operation.

“There was clearly a significant failure of response on behalf of the Malaysian Air Force. There’s no real way around it and you might imagine heads would roll for that,” says Anthony Davis, Bangkok-based analyst for defense-and-security-intelligence firm IHS-Jane.

According to Prof. Rohan Gunaratna, a security and terrorism expert at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, such lapses are not entirely surprising.

“European and North American militaries and governments respond to such anomalies and aberrations in aviation routes, but many Asian governments don’t as they are not paying such close attention,” he tells TIME. “Even if the government is informed, it may not take the same decisive action.”

Investigators believe that the Boeing 777-200 stuck to its intended flight path after first departing Kuala Lumpur International Airport at 12:41 a.m. on March 8, heading towards Beijing for around an hour. Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak told a press conference its Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System, or ACARS, was disabled just before the plane crossed over the Eastern coast the Malay Peninsula.

Shortly afterwards, the aircraft’s transponder cut out near the border between Malaysian and Vietnamese air traffic control. This would imply that the final radio contact of “all right, good night,” from the cockpit came after an attempt to conceal the 200-ton, twinjet aircraft’s location was already underway.

Malaysian officials initially seemed reluctant to direct any suspicion towards Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah or his co-pilot, Fariq Abdul Hamid, 27, who, it emerged last week, had previously invited two female passengers into the cockpit for an entire flight from Kuala Lumpur to the popular Thai holiday island of Phuket.

However, the backgrounds of everyone involved are now being thoroughly assessed. No leads have so far been identified although some governments with nationals on board have still to respond to requests for information, said police chief Khalid Abu Bakar. On Saturday, Malaysian police searched the homes of both Zaharie and Fariq. Zaharie apparently had a homemade flight simulator, which is now being examined.

Despite a refocusing on the pilots, the possibility of a hijacking has not been ruled out, and the final recording will be examined for any signs of stress. But investigators remain baffled by the absence of any distress call if hijackers had attempted to storm the cockpit. An airlines official has confirmed that “the pilot and co-pilot did not ask to fly together” on MH370.

Zaharie’s informal hand-off went against standard radio procedures, Hugh Dibley, a former British Airways pilot and a Fellow of the U.K. Royal Aeronautical Society, told Reuters. He should have to read back instructions for contacting the next control center and include the aircraft’s call sign.

The huge area in which the plane may have disappeared — from Northern Thailand to Kazakhstan, stretching down to the Southern Indian Ocean and even the West coast of Australia — makes finding any sign of the aircraft a daunting task, especially when wreckage may have floated hundreds of miles by now. On Monday, Australia announced it would lead southern search efforts.

However, analysts say it is unlikely the plane could have traversed the airspace of various militarized nations to the northwest without detection. “Once you move into mainland Indian airspace, let alone further northwest towards Pakistan and Afghanistan, I would be hugely surprised if an unidentified plane that had filed no flight plan would be able to penetrate their airspace without being challenged,” says Davis. “It would seem to me highly unlikely.”

During his Saturday press briefing, Najib maintained that his government “shared information in real time with authorities who have the necessary experience to interpret the data.” However, allegations of an attempted cover-up have been intense, especially from China. A total of 153 passengers were Chinese nationals.

“It would appear that there was an effort to fudge the result of that and the military did not pass the complete information onto the government,” says Davis, “hence the continuation of the search in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand for days later.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com