The mystery over the possible connection between hydraulic fracturing and earthquakes deepened on Mar. 10, when the Ohio government ordered a halt to operations at seven oil and gas wells near the Pennsylvania border after two quakes occurred earlier that day. While the quakes in Ohio’s Poland Township were too small to cause damage or injuries—they measured in at 2.6 and 3.0 on the Richter scale—the fact that one of the wells was undergoing fracking at the time of the quakes was enough for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) to suspend drilling operations in the area. “The decision was made out of an abundance of caution after analyzing location and magnitude data provided by the U.S. Geological Services” ODNR spokesman Mark Bruce said in an emailed statement.

Other than that, Ohio officials haven’t been saying much about the possible connection of the quakes to fracking operations—and neither has Hilcorp Energy, the Texas-based company operating in the area, which said in a statement that “we are not aware of any evidence to connect our operations to these events.”

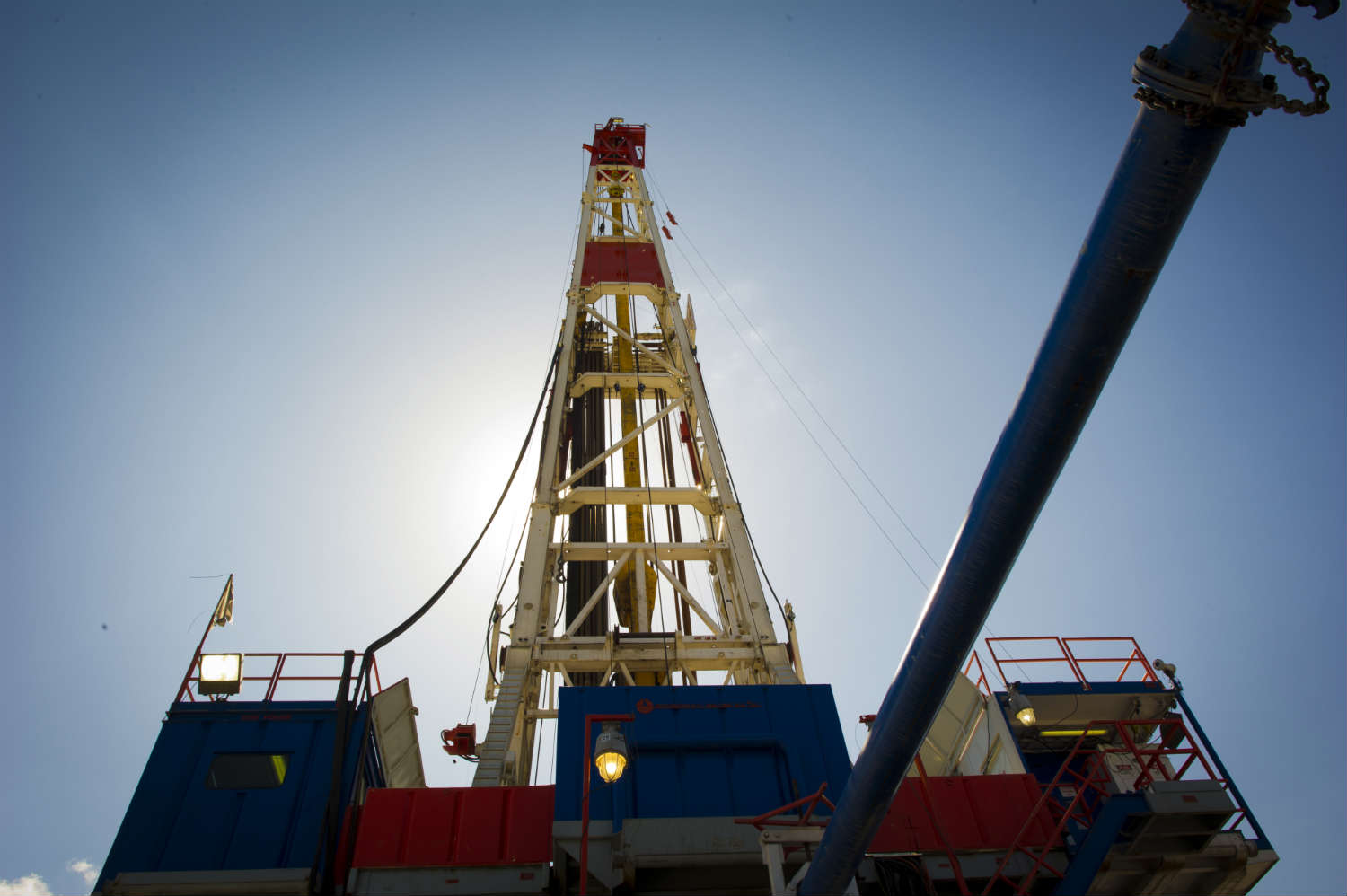

It will take more research to know if fracking at those wells directly led to the small quakes, but it’s not impossible. While there is a stronger connection between earthquakes and deep injection wells—where wastewater left over from fracking is disposed of by being piped at high pressures deep underground—there have been a few instances in which the act of fracking itself seems to have made the earth move. (In case you haven’t been paying attention, fracking involves the fracturing of shale rock thousands of feet below the ground, using millions of gallons of water and chemicals, to free up trapped oil and natural gas.) Quakes in British Columbia, England and south-central Oklahoma have been traced back to fracking—and since Ohio officials say there were no disposal wells in the area where the quakes occurred, it’s definitely possible that fracking could have played a role here as well, as retired Columbia University geology professor John Armbruster told the Columbus Dispatch:

It’s an area which (before 2011) had no history of earthquakes. It looks very, very suspicious.

What’s definitely suspicious is the astounding increase in earthquake activity in parts of the central and eastern U.S.—the same areas that have taken part in the fracking boom, as this chart from the USGS shows:

Nearly 450 earthquakes with a magnitude of 3.0 and larger occurred in the region in the four years from 2010-2013, over 100 per year on average, compared to an average rate of 20 earthquakes per year observed from 1970-2000. Last month, Oklahoma was hit by a wave of more than 150 minor earthquakes over the course of a week, including one that had a magnitude of 3.8, and today 10% of the quakes felt in the U.S. occur in the Sooner State. All of this is happening against the backdrop of the fracking revolution. In Ohio, oil production doubled between 2012 and 2013, and natural gas production increased by two and a half times.

The reason fracking itself does not trigger detectable seismic activity all that often is that the forces involved are relatively weak, and the fragile shale rock tends to fracture before it can build up much strain—which is, after all, the point of fracking. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible, just that it seems to pose less of a risk that deep injection wells, which involve far greater amounts of liquid and which have been known to trigger quakes since the 1960s. Here’s how the USGS put it:

Wastewater injection increases the underground pore pressure, which may, in effect, lubricate nearby faults thereby weakening them. If the pore pressure increases enough, the weakened fault will slip, releasing stored tectonic stress in the form of an earthquake. Even faults that have not moved in millions of years can be made to slip and cause an earthquake if conditions underground are appropriate.

Fracking has boomed across the country, as this excellent map from the Post Carbon Institute shows:

All the wastewater created by those fracked oil and gas wells has to go somewhere—hence the concurrent boom in disposal wells. Ohio has more than 188 such wells, with more being drilled, in part to take wastewater from Pennsylvania fracking after regulators in that state ordered oil and gas companies to stop dumping waste in streams. And while most of the quakes happening in frackland have been small, there have been some bigger ones, including a 5.7 magnitude quake in Nov. 2011 in Prague, Oklahoma that a USGS study this week linked to a disposal well. “The observation that a human-induced earthquake can trigger a cascade of earthquakes, including a larger one, has important implications for reducing the seismic risk from wastewater injection,” the study’s coauthor, USGS seismologist Elizabeth Cochran, said in a statement.

So induced earthquakes are definitely one more reason to worry about the rapid spread of fracking. But like most of the other concerns—potential groundwater contamination, spills and accidents, stress on small town infrastructure—seismic risk should be manageable with the right regulations. The USGS notes that there are some 30,000 wastewater disposal wells around the country, and “very few” seem to have the potential to cause quakes. Geologists know where fault lines are, and if we listen to them, we should be able to ensure that any new wells, whether drilled to get gas and oil or to store wastewater, are well clear of them. But until we do, don’t expect the shaking to stop.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com