Want to know the three people in the world who were the least interested this morning in the doings in Crimea? Try Michael Hopkins, Oleg Kotov and Sergey Ryazanskiy. If that group sounds like a decidedly American and Russian mix, that’s because it is, and the trio had much more immediate things to do today than argue over a bit of land by the Black Sea. What they were doing specifically was plunging into the atmosphere at a speed of just under 17,500 mph (28,100 k/h) from an altitude of 230 mi. (370 km), tucked shoulder to shoulder inside a metal sphere with just 88 cubic feet of habitable space—which sounds like a lot until you consider that it’s just 2.5 cubic meters.

The crew thumped down safely in Kazakhstan at 9:24 AM EDT on March 11, after 166 days in space together aboard the International Space Station, and by all accounts they got along splendidly. Space will do that to people. The stakes are so high, the margin for error so microscopic and the precise nature of the death that awaits you if you screw things up—spinning off into the void, burning up in the atmosphere—so terrible that you learn to prioritize quickly.

Even in the days of the real Cold War, the one with all of the ICBMs poised and armed and ready to launch, the U.S. and the Soviet Union quietly had each other’s backs in space. On January 27, 1967, Lyndon Johnson, Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, a gaggle of dignitaries from 60 countries and a delegation of American astronauts gathered in the Green Room of the White House for the formal signing of the clumsily named “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space.” The agreement committed all signatories to keeping space forever non-militarized, to making no land claims on the moon or any other cosmic body and to offering all assistance to any astronauts in distress from any nation.

It is a matter of historical record that at 6:32 PM that night, even as the White House reception was still underway, a fire was breaking out in the Apollo 1 spacecraft on its launchpad at Cape Canaveral, where astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee were rehearsing liftoff procedures. It is a matter of historical record too that by 6:34 all three were dead. Many of the same dignitaries from the same 60 countries who had planned to travel home the next day instead stayed around to attend the funeral of three men who would never fly again.

So the stakes have always been high.

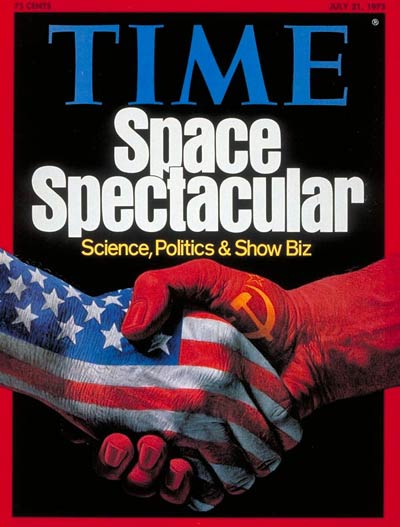

Over the years, even before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the cooperation endured. The Apollo-Soyuz flight in 1975 saw spacecraft from the U.S. and U.S.S.R. meet and dock in orbit for the first time, just months after U.S. embassy personnel had made their ignominious withdrawal from a rooftop in Saigon and the USSR collected one more domino. In the 1990s, American astronauts regularly flew aboard Russia’s Mir spacecraft, and in the 2000s, multi-national crews, particularly those from the U.S. and Russia, have spent extended periods aboard the International Space Station.

Yes, national self-interest endures. For years, Russian Soyuz rockets helped ferry NASA astronauts up to the ISS, and our crews weren’t paying for their tickets in miles. The price per seat was $22 million in 2006, jumped to $43 million in 2011, as the shuttle program was winding down, and is now $71 million—a price we have no choice but to pay if we want to get Americans into space at all. Hey, back in the bad old days we argued that Russia would do better under capitalism; well, this is how capitalist countries behave.

It’s true too that while the world applauded the U.S. moon landings, there wasn’t a Frenchman or Russian or Turk alive who wouldn’t have preferred seeing a lunar astronaut saluting the tricolor or the hammer and sickle or the star and crescent instead of the stars and stripes. And if China beats us back to the moon or even on to Mars, we’ll gnash our teeth too.

But space travel is inherently an enterprise that knows no national identities. It is an old but no less apt observation that astronauts can’t see borders from space. That doesn’t stop the rest of us from drawing them—in Crimea and Kurdistan and the West Bank and anywhere else we decide to fight with the folks next door. If we ever stop doing that—grow out of our stay-on-your-side-of-the-line! impulses—the experience will be a novel one for the species, or at least most of the species. Spacemen and spacewomen and the folks who send them aloft have already had a taste of it. By all accounts, they like it just fine.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com